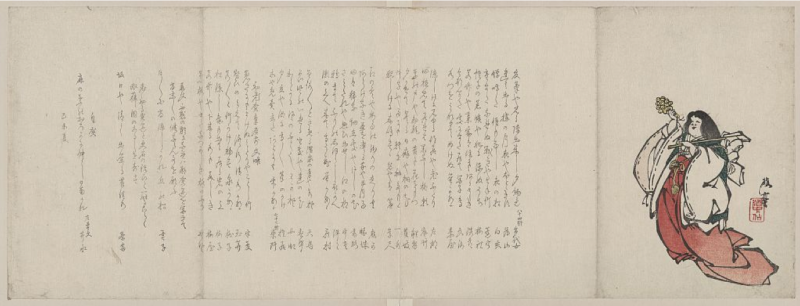

Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto woodcut by the artist Katei Hōjō (1780-1823).

Portland String Quartet

T. Allen LeVines – Travel Journal; Dorothy G. Britton – “Chinoiserie” Histoire d’un Amour Oriental

Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto

[Whirling Goddess]

String Quartet No. 4

T. Allen LeVines

When is there not music? … bursts of morning sun or night shadows in a full moon rising … thundering spring waterfalls or silent mountain snows in winter … flanks glistening on unbridled horses or petals drooping on dew-soaked wildflowers …

Where is there not music? Charles Ives asks if music can express “a stonewall with vines?”1 Reciprocally, can stonewalls with vines express music? Does music’s power depend on a story, or a story’s power depend on its music – its rhythm? Can art reflect knowledge or spirituality? Can it be that knowledge and spirituality are mirror images of art? If these questions have answers, do the answers have substance? Over and over questions seem to emit sheens of energy while answers consistently lie empty.

To “believe that music is beyond … word language” is Ives’ proposal; that music “will develop possibilities inconceivable now, – a language, so transcendent, that its heights and depths will be common to all”1 humanity. But what is language? In application is it not perpetually translation? Is it not a desire to translate thought and feeling? Is it not a desire to carry our pasts forward? Current science claims that we bring our heritage in all its aspects with us, that it is immovably encoded within the patterns of our DNA architecture. As George Rochberg muses, “Each of us is part of a vast physical-mental-spiritual web of previous lives, existences, modes of thought, behavior, and perception; of actions and feelings reaching much further back than what we call ‘history.’ We are filaments of a universal mind; we dream each other’s dreams and those of our ancestors. Time, thus, is not linear but radial.”2 And space, then, is not mere curved lines but omni-directional, multi-dimensional spirals.

At the dawning of the 21st century, related ideas began gaining legitimacy, spawning passionate excitement across the scientific community, and spreading to other disciplines as well. In the late 1960s, the first explorations in string theory took shape, with many waves of discoveries emerging a few decades later leading to superstring theory. All “subatomic particles we see in nature,” asserts physicist Michio Kaku, “are nothing more than different resonances of the vibrating superstrings,”3 strings which are unimaginably small, about 100 billion times smaller than a proton. “Likewise, the forces between particles are the harmonies of the strings; the universe is a symphony of vibrating strings. And when superstrings move in ten-dimensional space-time, they warp the space-time around them in precisely the way predicted by general relativity. So strings simply and elegantly unify the quantum theory of particles and general relativity. [Moreover,] string theory requires gravity.”3 As physicist Sunil Mukhi rephrases, “It is almost as if gravity needs strings in order to exist.”4 If string theory is correct, then the known world – time, space, force, distance, mass, sight, and sound – is but innumerable vibrating strings expressing an array of frequencies.

Well before the modern scientific era the substance of these ideas was contemplated. In Wu-wen Kuan, by 13th century Ch’an master Wu-men, time’s incomprehensibly flexible nature is recognized,

無量劫事即如今。

如今覷 破箇一念

覷 破如今覷底人。

eternal time is just this moment.

If one sees through this moment’s thought,

one sees through the one who sees through this moment. 5

The 1st century author of the Gospel of John professed logos (λογος) or the word to be the progenitor of all things – the creating power,

εν αρχη ην ο λογος, και ο λογος ην προς τον θεον, και θεος ην ο λογος. παντα δι αυτου εγενετο, και χωρις αυτου εγενετο ουδε εν. ο γεγονεν

εν αυτω ζωη ην, και η ζωη ην το φως των ανθρωπων.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. All things were made by [the Word]; and without [the Word] was not any thing made

that was made.

In [the Word] was life; and the life was the light of [all people]. 6

In a similar manner the concept of logos was given by Heraclitus before 400 BC. Logos’ accepted English translation as “word” approaches both “sound” and “vibration” in meaning.

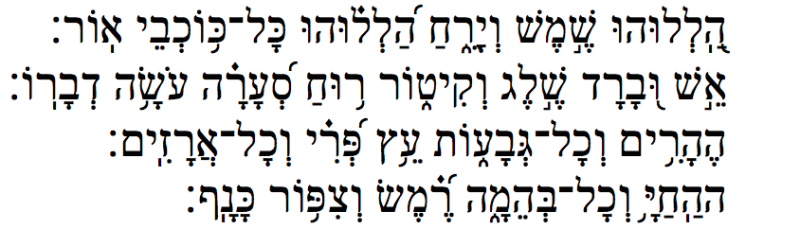

A universe alive with resonance is assumed repeatedly in the Tehillim of the Tanakh,

[Hallellujah!] Praise the Lord, sun and moon: Praise the Lord, all bright stars.

Fire and hail, snow and smoke, storm wind that executes his command.

Mountains and hills, all fruit trees and cedars.

All wild and tamed beasts, creeping things and winged birds. 7

Moreover, nearly four-thousand years ago the Rig Veda imagined the mysteries of reality as fabric – actively being woven and in motion,

नाहं तन्तुं न वि जानाम्योतुं न यं वयन्ति समरेऽतमानाः |

… वक्त्वानि … ||

I know not the woof, I know not the warp, not what is this web that they weave moving to and fro in the field of this motion and labour … These are secrets that must be told … 8

These are inquiries, conversations, and traditions to which I have been drawn for a quarter century. Poetry? philosophy? science? mysticism? Expanding Fuller, “I seem to be a verb,”9 noun, adjective, and adverb – not one or another. May it be that Ives’ “common language” exists now – and has always? That music is nothing less than all we know of time and place? That in witnessing the mechanics of the cosmos and the earth, and in embracing the grand array of reverberations from all humankind, our lives are opened to questions that are indeed transcendent?

大器晚成

大音希聲

大象無形。

道隱無名

道隱無名

The great vessel is never finished.

The great tone is never heard.

The great thought can’t be thought.

The Way is hidden in its namelessness.

But only the Way begins, sustains, fulfills. 10

– Lao Tzu

Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto scroll created by Sen Sen Dai Guji Yamamoto Yukiter (early 20th c.), the 95th High Priest of Tsubaki Grand Shrine, one of Japan’s oldest Shinto shrines.

Amaterasu and Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto

… As the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu, sat in her sacred weaving-hall seeing to the weaving of the sacred garments of the gods, the Storm God, Susano-o, broke a hole in the top of the weaving-hall, and through it flung a heavenly piebald horse which he had flayed. The maidens weaving the sacred garments were greatly alarmed, so that they struck themselves against the shuttles and died.

Amaterasu, terrified at the sight, closed behind her the door of the Rock-cave of Heaven and sealed it, secluding herself inside. Now the whole of Heaven was obscured and all the lands of the earth darkened, and eternal night prevailed… Then the eight hundred myriad gods joined in divine assembly on the banks of the Tranquil River of Heaven, and the God of Far-reaching Thought conceived a plan. Thus the cocks of eternal night were gathered and made to utter their prolonged cries, the sacred hard rocks of Heaven were taken from the river-bed, and the iron was taken from the Heavenly mountains. The Smith of Heaven was sought, and the Forging Goddess was called upon to make a mirror. The gods were charged to make a necklace – a sacredly complete string of jewels – eight feet long of five hundred jewels… The gods were summoned to pull up a sacred sakaki tree by its roots with five hundred branches from Heavenly Mount Kagu, and on its upper branches they placed the string of jewels. To the middle branches they tied the mirror eight feet long, and on its lower branches they hung the white mulberry cloth offerings and the blue hemp cloth offerings. The gods took all these things and held them together with the sublime

offerings, and prayerfully intoned magical incantations, as the God of Great Hand-strength stood hidden beside the door.

Then Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto, the Whirling Goddess, hung clubmoss around her as a sash, and made a spindle-tree her head-dress, and bound leaves of bamboo-grass in a wreath for her hands. She placed an upturned basin before the door of the Rock-cave of Heaven, and stamped resoundingly upon the upturned basin and danced as if divinely possessed, and pulling out the nipples of her breasts, and pushing down her skirt-band, stripped herself naked. Then the Heavens shook, and the eight hundred myriad gods burst forth together with joyous voices. Amaterasu was amazed, and opened a narrow space in the door of the Rock-cave of Heaven, and spoke from the inside, “I thought that the Heavens would be dark, and that all the earth would be dark. How can it be that Uzume sings and dances, and that the eight hundred myriad gods are filled with joy?” Then Uzume spoke saying, “We rejoice and are glad because there is a deity here more illustrious even than you.” While she was speaking, the gods pushed the mirror eight feet long forward and showed it to Amaterasu. She grew more and more astonished, and gradually came out of the door and gazed upon her reflection. Then the God of Great Hand-strength who was standing hidden, took her sacred hand and drew her out, and then the gods pulled the bottom-tied straw rope along at her sacred back and spoke, saying, “You must not go back further in than this!” Thus when Amaterasu had come forth, both the whole of Heaven and all the lands of the earth became light … 11

The ancient Shinto myth of Amaterasu and Ame-no-Uzume is the focal point for my Fourth String Quartet, written as a possible translation of the legend into sound. Further illumination of both myth and music may be explored in performances through the addition of dance. Little in my Fourth String Quartet can be considered original. Like Rochberg, I am unpersuaded by the “notion of originality,” a limiting conceit of questionable reasoning “in which the personal style of the artist and his ego are the supreme values.” My quartet’s large scale pitch design comes out of George Perle’s concepts for cyclic sets; melodic idiom emanates from the masterful shamisen artistry of Senri Yamada; closing rhythmic patterns pay homage to Torgbui Midawo Gideon Foli Alorwoyie’s generous teachings in Ghanaian drumming. To these remarkable musicians and traditions I owe my deepest respect and gratitude.

– T. Allen LeVines, 19 February 2008

*Whirling Goddess

Deserting the heavens

the abused sun goddess seals herself

deep within a cave

Earth falls endlessly

into blackest night

Before the cave door

under the jeweled sakaki

Uzume dances

Uzume courts and sparks

on an overturned basin

with drumming feet

Climbing to divine ecstasy

Uzume strips herself bare

Naked Uzume dances

eight hundred myriad gods raise a joyous uproar

A flash from the Sakaki tree mirror

captures Amaterasu’s gaze

Rising from the void

brilliant cascades of sun gold

Amaterasu!

* Verse rendering of Amaterasu and Uzume legend, – T. Allen LeVines and Raffael de Gruttola.

2 George Rochberg, String Quartet no. 3, Concord String Quartet, Nonesuch Records HQ-1283.

3 Kaku, Michio. “Into the Eleventh Dimension,” New Scientist 153-2065 (January 1997).

4 Mukhi, Sunil. “String Theory and the Unification of Forces.”

http://theory.tifr.res.in/~mukhi/Physics/string.html (cited 28 Dec. 2006).

5 Wu-men Wu-wen Kuan (trans. Katsuki Sekida), case 47. In Two Zen Classics. New York: Weatherhill, 1977.

6 John 1:1-4. Christian Bible (Stephanus NT; KJV).

7 Tehillim [Psalms] 148:3, 8-10. Tanakh [Hebrew Bible] (JPS, 1999).

89 Fuller, R. Buckminster. I Seem to Be a Verb. New York: Bantam Books, 1970.

10 Lao Tzu. Tao Te Ching (rendition Ursula LeGuin), 41: 14-19. In Tao Te Ching. Boston: Shambala, 1998.

11 Kojiki (trans. Basil H. Chamberlain), volume 1, sections 15-16. In Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters). Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1982. (rendition T. Allen LeVines, 2006).