In the days leading up the premiere, newspapers and magazines published articles that followed a certain formula: they introduced Shostakovich to readers unfamiliar with his music; documented his struggle to complete the Seventh Symphony during wartime; described the battle royal among prominent American conductors for “first performance” honors; noted NBC’s clandestine negotiations with Am-Russ Publishers for broadcasting rights; and traced the score’s epic journey from Soviet Russia to the West.[2] Reviews, however, were mixed. Newsweek noted a schism between critics, who panned the symphony’s “length and loose construction,” and audiences, who embraced its themes of “heartbreaking sadness,” “thundering resolute might,” and “brooding suspense”—a schism rooted in an ongoing debate about classical music on the radio.[3]

That debate stretched back to the early 1920s, when commercial radio broadcasting first promised to introduce millions of Americans to “good” music, the era’s catch-all term for symphonies, operas, and light classics. As a new body of music appreciation literature emerged to meet the needs of these tyro listeners, certain cultural critics—epitomized in their most extreme form by Theodore Adorno—argued that flashy, programmatic music was eclipsing purely symphonic music on the radio and in the concert hall, thanks in no small part to music educators, whose efforts to teach the public about classical music amounted, in Adorno’s view, to nothing more than the mere accumulation of facts about instruments, genres, and composers.[4] At the same time, another group of writers, often working in close concert with the NBC or CBS radio networks, championed the idea that classical music could be music for the masses, arguing that that the popularity and sensory appeal of program music made it an ideal point of entry for newcomers.

Though both sides were united in their goal of helping Americans appreciate classical music on the radio, their conflicting ideas about how best to achieve this goal were laid bare by the premiere of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, as were their ideas about Russian and Soviet culture.

To understand the discourse surrounding the symphony’s premiere, we need to revisit the early twentieth century, when the Victorian mania for self-improvement compelled many bourgeois Americans to form music appreciation societies. Shifting work patterns, especially the advent of the forty hour week, facilitated this mania for clubs by granting middle-class Americans a new form of capital: leisure time. Upwardly-mobile Americans spent this capital on educational pursuits, joining clubs that sponsored lectures, gatherings, concerts, and guided tours. They also spent money on books that promised to introduce them to repertoire beyond the parlor songs and hymns popular with amateur musicians.

With titles like The Book of Musical Knowledge (1915) and Masters of the Symphony (1919), these tomes promoted the idea that the “degree of enjoyment must be commensurate with the degree of understanding.” Authors provided basic information about the classical repertory—titles, dates, genres—and declared absolute music superior in conception and execution than program music.[5] In Masters of the Symphony, for example, author Percy Goetschius argued that the symphony represented the “highest type of musical composition,” ruling out opera, oratorio, and program music because they relied on extramusical material and orchestral “tricks” for their nakedly “sensuous appeals.” “Whatever extraneous elements are thus added to music,” he opined, “must inevitably hamper the free, unconstrained unfolding of the true, pure musical spirit, and adulterate or obscure the main issue.”[6] Study questions at the end of every chapter stated the supremacy of certain composers and genres as fact, even asking readers to identify “two fundamental qualities” that “the genius of Mozart manifests.”[7]

The expansion of radio broadcasting across the 1920s and 1930s spurred the publication of even more textbooks, instructor’s manuals, “how-to” guides, program notes, and encyclopedic volumes devoted to particular genres. Though these texts professed to serve the needs of the “man in the street,” for whom “the enjoyment of classical music is a new sensation,” their authors still assumed a certain amount of knowledge on the part of the reader, using musical terminology without explanation and illustrating important moments from symphonies and concerti through piano reductions.[8] These authors perpetuated the same condescending attitudes towards certain composers and genres, singling out program music for special abuse. In his anthology of “radio talks” entitled The Well-Tempered Listener (1940), composer Deems Taylor argued that program music burdened the composer with “dramatic” concerns that compromised his ability to rigorously develop musical ideas within a recognizable framework such as sonata form. “A man who writes a string quartet or a sonata or a symphony can develop his themes in terms of purely musical logic,” he opined. “But let him start to paint a picture or tell a story, and he finds himself confronted by the necessity of making sudden changes in speed and rhythm, and harmonic excursions into unexpected keys, not for musical, but for dramatic reasons.”[9]

In many such texts, authors seemed uncomfortable with the idea that radio was democratizing access to classical music. The second edition of Arthur Elson’s The Book of Musical Knowledge (1927), for example, was quick to point out that in the twelve years since the first edition was published, “the advent of the radio has brought music before a much larger public.” As a result, Elson claimed, “music was no longer the property of the elect,” that a large class of listeners had, in effect, become enfranchised and would help determine the future of good music on network radio. When exercising their vote, however, listeners had a duty to educate themselves so that they could distinguish the vulgar from the refined.[10] “It is to be hoped that along with this willingness to listen to the best will go a desire for information about music and its composers, and an interest in elements of musical composition,” Elson argued. “Then the pleasure which radio affords will rest on a firmer and more enduring basis.”[11]

Other authors, however, embraced a more populist approach by explicitly courting radio owners. Hazel Gertrude Kinscella, author of Music on the Air (1934), described listening to radio broadcasts as a leisure activity that required little specialized knowledge or study. “In writing this book,” Kinscella declared, “music has been considered especially as a leisure-time enjoyment. All listeners, whether musically trained or not, will have their pleasure in any piece increased by knowing the meaning and interpretation the composer had in mind when he wrote, whether his music is engaging for its formal beauty or for its ‘story.’”[12]

As Kinscella’s introduction suggests, these texts sought to reassure novice listeners that, armed with the right information, they would no longer be disappointed or puzzled by classical music. In the foreword to the 1930 edition of the NBC Music Appreciation Hour Instructor’s Manual, conductor and program host Walter Damrosch informed readers “the foregoing talks may help you to adjust your taste so that you will not be confused and displeased, by wrong expectations, as though you were all ‘set’ for the taste of coffee and received a root beer instead.”[13] Schima Kaufman’s 1938 book Everybody’s Music, “published with the cooperation of the CBS network,” made similar claims: the dust jacket enticed potential buyers with the promise that information, easily indexed and presented in a conversational, “intimate” style, would enhance their appreciation of classical music. “When you hear music over the radio or at a concert,” the copy read, what “makes it a hundred times better is you can reach for a book and find out about what you are hearing—about the composer, and about his other works. That is exactly the kind of a book this is, a new approach to musical enjoyment.”[14]

In addition to emphasizing factual information, these texts stressed recognition as a key to musical enjoyment. Some authors, like Sigmund Spaeth—notorious for his “how-to” books Great Symphonies: How to Recognize and Remember Them (1936) and Great Program Music: How to Enjoy and Remember It (1940)—believed that the primary obstacle to enjoying a symphony was the fact that many listeners could not identify and remember the principal themes long enough to recognize the role they played in articulating a movement’s form and shaping its development. By fitting famous themes with appropriate words, he argued, he was reviving an age-old pedagogical technique for enhancing memorization. “The idea is not a new one at all,” he noted. “It has been applied to all kinds of information, such as the names of the Presidents of the United States and the Kings of England, the alphabet and multiplication table.”[15] For Dvorak’s New World Symphony, for example, he composed a simple rhyme describing the plaintive quality of the English horn’s famous second-movement solo that could be sung to the tune of “Goin’ Home.”

Spaeth’s peers adopted a more catholic approach to the problem of theme recognition. Kinscella, who shared Spaeth’s belief that “to appreciate one must first listen for something in particular,” used simple vocal reductions of complex orchestral passages, usually transposed to the keys of C or F Major.[16] The most extreme example of this trend, however, was Symphonic Themes, published in 1942 by Simon & Schuster. The volume contained no information about composers or compositions, just themes indexed alphabetically by composer and work. Cultural critics such as Theodore Adorno attributed this fetishization of themes—already prevalent in music appreciation courses and textbooks at the turn of the century—to the rise of radio broadcasting across the 1920s and 1930s, and castigated music educators and the NBC Music Appreciation Hour alike for promoting the idea that “serious music fundamentally consists of important themes with something more or less unimportant between them.”[17]

At the same time Adorno was disparaging Spaeth and Damrosch’s work, researchers, advertising agencies, and broadcasters were beginning to survey listeners for insight into what programs were popular, and which products listeners bought.[18] Though many of these surveys were intended to help network executives make sound business choices, the idea of the survey as a scientific measure of consumer behavior and listener preferences trickled down into the music appreciation literature. In the introduction to Music on the Air, Kinscella approvingly described a survey in which 500 radio listeners were asked to rank their favorite pieces of classical music. “It is seldom that any two people agree upon a single composition, but when five hundred agree upon ten pieces of music it is a fair test as to the type and quality of music that the general public likes best. The ten pieces in the order of their popularity are:

“To a Wild Rose” MacDowell

“Spring Song” Mendelssohn

“Barcarolle” (Tales of Hoffman) Offenbach

“Melody in F” Rubinstein

“Humoresque” Dvorak

“Anitra’s Dance” (Peer Gynt) Grieg

“Traumerei” Schumann

“Largo” (New World Symphony) Dvorak

“Hallelujah Chorus” (Messiah) Handel

Even those who professed that “popularity” was a dubious measure of a piece’s worth still found it a useful principal for deciding what to include in volumes such as the Victor Talking Machine Company’s Book of the Symphony, Book of the Overture, and Book of the Opera. In the introduction to the revised 1941 edition of The Victor Book of the Symphony, for example, author Charles O’Connell explained his methodology in a positivist tone: “a standard derived from the known popularity of each work, as demonstrated by the frequency of its appearance on the programs of four major American symphony orchestras during the past three years, has been applied.”[20]

These simplified musical illustrations and top-ten lists indicate that radio evangelists had a somewhat different conception of music than their more staid counterparts. Though both groups prized melody, the radio evangelists felt that a discernible structure was less essential to good music than musically arresting gestures. As a result, they embraced genres and composers derided by their peers, including Russian music.

Defining Russian Music

Although these two camps defined good music differently, both the champions of high art such as Goetschius, Taylor, and Elson, and the radio enthusiasts such as Kinscella, Kaufman, and Damrosch, agreed that Russian music was naïve, exotic, and emotional, filled with folkloric themes and pungent harmonies that seldom coalesced into a unified whole. Such notions of Russianness enjoyed broad currency in Western Europe and the United States in the early twentieth century. In his books Studies in Russian Music (1935) and On Russian Music (1939), for example, British musicologist Gerald Abraham argued that Russia was “a nation with more marked psychological tendencies than any other in Europe.” He characterized the Slavs as “illogical” in contrast to Teutons and Anglo-Saxons, suggesting that Slavs were easily seduced by the sensual appeal of a heavily ornamented surface or brilliant sound-color.[21] Because of his diminished critical faculties, Abraham opined, the Russian “seems usually to be over-concerned with the thrill of the present moment in sound.” Russians lacked the “broad and retentive” “mental vision” that enabled other “races” to derive pleasure “from Brahms and Beethoven at their best, when we feel that… the composer has ‘foreseen the end in the beginning and never lost sight of it.’”[22]

This idea that Russian music was particularly suitable for children and novice listeners reflected an elitist tendency to assume that only knowledgeable listeners could appreciate the beauty and complexity of a Brahms symphony. Such critics viewed a Tchaikovsky ballet as the first step in a child’s journey to musical connoisseurship; though it was filled with bright colors and memorable motifs that might excite a young mind, and inspire youthful interest in classical music, it lacked the formal sophistication that mature listeners esteemed. In his 1924 book From Song to Symphony, for example, composer Daniel Gregory Mason contrasted the “chaste and reticent nobility” of Brahms with the “exaggerated, vulgar, and often cloying sentimentality” of Tchaikovsky. In particular, he criticized Tchaikovsky’s music as architecturally unsound, arguing that the proportion and foreshadowing of Brahms’ “intellectual” style were absent from Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony. “Where Brahms would make a magnificent climax of thought as well as of sound, through the long forseen fulfillment of ideas,” Mason opined, “Tchaikovsky plays rather upon our senses and our nerves only, and the thrills he sends up our spines leave our brains untouched.” In short, Tchaikovsky was incapable of fashioning themes into “an integral work of art.”[25]

The test materials in music appreciation texts further reinforced these stereotypes. In Masters of the Symphony, for example, Goetschius posed the question, “Which race has produced the majority of Classic masters?” at the end of his chapter on “Listz, Tchaikovsky, Dvorak, Sibelius,” implying that these other, non-German composers were anomalies.[26] Even Tchaikovsky’s partisans conceded that his music lacked the clarity and balance of the classical masters. In a radio talk preceding a program of Mozart and Tchaikovsky, critic Olin Downes characterized Mozart as “an artistocrat of art,” while Tchaikovsky, with his undeveloped themes and messy structures, was a kind of noble savage endowed with a crude musical faculty. “Tchaikovsky,” Downes told listeners, “is a child of the earth, and of the nation of Pushkin and Dostoievsky”—as if the very fact of Tchaikovsky’s Russian origins was enough to explain his musical shortcomings.[27]

Though no clear stereotype of the Soviet composer existed in the music appreciation literature of the 1920s, by the 1930s an archetypal Soviet composer began to take form in journal articles and how-to books alike. He shared some of the same traits as the earlier generation of Russian composers, though authors frequently portrayed the Soviet musician as a humorless ideologue preoccupied with Communist themes. When a composer’s music displayed feeling or tunefulness, authors suggested that he was either reverting to some atavistic Russianess not squelched by Soviet censorship, or was composing in a deliberately international style in defiance of party dictates. In particular, authors disparaged Soviet Socialist Realism for fostering an aesthetic heavily dependent on sensational musical effects.

The Victor Book of the Symphony typified this approach, characterizing composer Alexander Mossolov (1900-73) as a creature of the Soviet system. Though he was “one of the more important younger Russian composers, most of whom are or have been engaged in music which attempts political propaganda,” author Charles O’Connell noted, Mossolov was capable of writing music of “great charm.” Unfortunately, O’Connell continued, Americans were only familiar with Mossolov’s Soviet Iron Foundry (1926), a piece marred by disorganization, orchestrational gimmickry, and an obvious, extramausical program. “There is nothing startling about the piece except its complete formlessness,” O’Connell opined. He attributed its primary shortcomings to its industrial theme, which required the composer to sacrifice motivic development to the reproduction of the foundry’s “flaming forges, shadowy figures darting, and ceaseless activity.”[28] In contrast to the entry on Mossolov, O’Connell’s discussion of Sergei Prokofiev glowed with praise. O’Connell characterized Prokofiev as that rare member of “the musical hierarchy of the Soviet Republics today” whose cosmopolitan style transcended the vicissitudes of Soviet realism.[29] “Rarely has he fallen to the mischievous delusions of extreme musical radicalism,” O’Connell informed readers. “He has demonstrated the soundest kind of composition, even to writing a charming symphony in the classical manner.”[30]

Many of the ideas found in contemporary music appreciation books carried over into newspaper reviews of Shostakovich’s earliest compositions: the importance of “melodiousness” and “recognizable tunes” to enjoyable listening; the inability of Russian composers to create works of structural integrity or profound emotion; and the Soviet predilection for “blatant” and “banal” program music calculated to appeal to a vast proletariat. In a 1935 New York Times editorial entitled “Two Russian Composers: Comparing Stravinsky and Shostakovich,” Olin Downes represented Igor Stravinsky as the true artist of the pair, noting that Stravinsky fled Bolshevik Russia for Paris while Shostakovich remained behind, captive to Soviet ideology; whatever innate value a work like Shostakovich’s 1934 opera Lady Macbeth of Mtensk might possess, it would be consigned to the “wastebasket” of music history for its Soviet realist agenda. “His opera cannot last,” Downes predicted, for “it is so clearly a product of its particular day and environment in Russia that it cannot be expected to survive the modifications of ideas which within a few years culture will bring in the country of origin.”[31]

The subsequent dissemination of Pravda infamous 1936 editorial “Muddle Instead of Music” engendered a peculiar response from some American observers, who agreed with Stalin’s scathing critique of Lady Macbeth.[32] New York Times reporter Harold Denny approvingly cited Pravda dictum urging composers to return to “Shakespeare, Beethoven, Pushkin, and Glinka” as well as indigenous musical traditions, at the same time ignoring the peril that Shostakovich faced for offending the Party. “As a result of this tempest in a trombone,” Denny cheerfully predicted, “Soviet composers undoubtedly will pay more attention to the rich musical material to be found in the folksongs of the Soviet Union’s many component nationalities.”[33] In another New York Times article, the anonymous author established Stalin’s credentials as a music critic, arguing that a combination of ecclesiastical musical training and “innate musical taste” common to “most Georgians” afforded Stalin the necessary perspective for evaluating Lady Macbeth of Mtensk.[34]

Other observers, such as Olin Downes, employed more oblique strategies, unfavorably contrasting Lady Macbeth of Mtensk with And Quiet Flows the Don (1935), an opera by Shostakovich’s contemporary Ivan Djerjinsky and based on Mikhail Sholokov’s four-volume epic (1928-32). Downes lauded Djerjinksy’s use of folkloric tunes and ingratiating, tonal melodies. Though his opera was “simplistic” and sometimes “derivative,” Downes praised Djerjinksy for selecting a source-text of “Tolstoyan frame and breadth of design,” capable of truthfully representing the “the soul of a distracted and agonized people” to the outside world—in essence, of representing the “real Russia” of Glinka, Tchaikovsky, Pushkin, and Turgenev.[35]

Only after the successful 1937 premiere of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony did American critics appraise his work favorably. Writing about the New York premiere of his String Quartet No. 1 (1938), the New York Times enthusiastically reported that the piece was “full of melody.” Shostakovich “has obviously taken inspiration from Russian folk music,” the unnamed author declared, “for the final allegro… suggests a Russian carnival, and the beautiful melody first enunciated by the viola… has the mournful quality of some of the Russian laments.”[36] Howard Taubman’s 1941 record review of the Sixth Symphony and Piano Quintet offered similar praise, suggesting that in these two post-1936 works, Shostakovich had rediscovered his authentic “Russian” self. In the “abundance of fresh and easily recognizable themes,” Taubman opined, “there is no mistaking the essential romanticism of the composer nor his Russian roots.”[37]

Evaluating the Seventh Symphony

The attitudes embodied in the media coverage of the Leningrad can be explained, in part, by the political environment in which it premiered. Though Hitler’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union transformed a former enemy into a critical ally, a massive propaganda effort was needed to undo twenty years of anti-Communist rhetoric in the United States. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, for example, dispatched Vice President Henry Wallace to address the Congress of Soviet-American Friendship at Madison Square Garden on November 8, 1942. Wallace’s speech recast Russian history in distinctly American terms, arguing that geography and progressivism shaped the destinies of both cultures, as did a contempt for monarchy. “It is no accident that Americans and Russians like each other immediately when they get acquainted,” he assured his audience, for

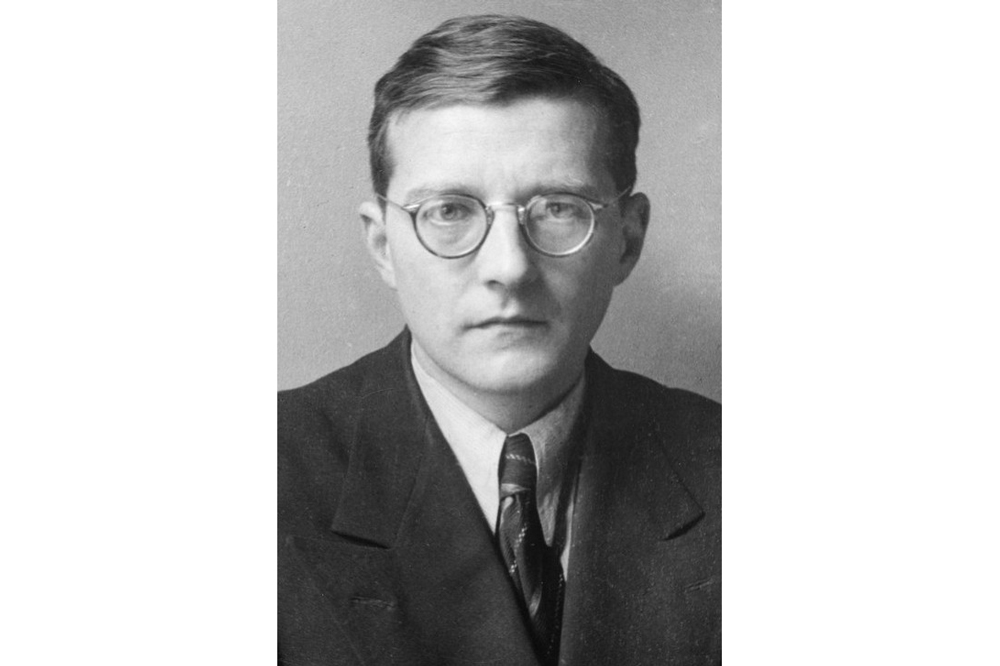

Life magazine helped promote this new vision of the Soviet Union in a photo essay about the symphony’s premier. The article featured images of Shostakovich as a young boy and a volunteer fireman, while captions emphasized the propaganda value of his music, noting that the Leningrad depicted the “violence and agonies of the war which the 36-year-old composer himself was helping to fight.” Throughout the essay, Life editors portrayed Shostakovich as both an exceptional talent and an ordinary Soviet citizen, while scrupulously avoiding any reference to the composer’s much-maligned Lady Macbeth of Mtensk:

The broadcast, however, elicited mixed reviews, particularly from prominent New York critics. While Time, Newsweek, and The New Yorker praised Shostakovich for the dramatic intensity of his music, others condemned him for writing a symphony that appealed to the senses and not the intellect. The Nation’s music critic B.H. Haggin, for example, disparaged the symphony as the sort of obvious music that appealed to uneducated audiences. In language that echoed earlier criticisms of Tchaikovsky, Haggin declared:

Other critics took a more positive—if measured—stance about Shostakovich’s new work, viewing it as as dramatic, accessible, and appealing to the general listener. The New York Herald-Tribune’s Francis Perkins assured readers that the symphony’s “programmatic course is easily understood” even “without any advance information,”[44] a point echoed by New Yorker critic Robert Simon. “Although it’s a long symphony,” Simon noted, “it isn’t difficult listening. The details of the work may be complicated for the performers, but the hearer knows where he is, and in some episodes, such as the extended buildup of a simple phrase in the first movement and the powerful, affirmative finale, the listener is likely to find himself excited.”[45]

As Simon’s comments suggest, the symphony’s structure and length—one hour and twelve minutes in performance—were the focus of much criticism. Only Time magazine’s anonymous reviewer felt these qualities were essential to its success. Though it suffered from quintessentially Russian flaws—there was “little development of its bald, foursquare themes” and “no effort to reduce the symphony’s loose, sometimes skeletal structures to the epic compression and economy of the classical symphony”—the reviewer felt these flaws served a didactic purpose, and represented intent on the part of the composer. He argued that “this very musical amorphousness is expressive of the amorphous mass of Russia at war.”[46]

Even readers felt compelled to join the conversation over the symphony’s merits. In a letter dated August 18, 1942, reader Ethel S. Cohen commended B.H. Haggin, The Nation’smusic critic, for “resist[ing] herd emotion” in his evaluation of the recently-premiered Seventh Symphony. She argued that the tremendous publicity preceding NBC’s broadcast overshadowed the symphony’s “eclecticism, sterility of inventiveness, and repetitious rhythmic and distorted harmonic patterns.” “Would it not have been more salutary,” she asked, if Shostakovich’s symphony, “written though it was under the most extraordinary circumstances, had been presented without all the advance ballyhoo attendant on its arrival?” Such “extravagant” press coverage, Cohen declared, created a false set of expectations among listeners, who had been conditioned by newspaper and magazine articles to expect “a work surpassing Beethoven’s Ninth.”[47]

Conclusion

At bottom, what these letters, articles, and reviews reveal is a spirited public contest over the place of good music in American culture. Both sides agreed that radio offered a unique platform for introducing millions of listeners to classical music, but disagreed over what kind of music should be broadcast. Populists championed the idea that new listeners would gravitate more naturally to program music, while absolutists feared that capitulating to public taste would persuade the networks to focus on superficial works that lacked the formal rigor prized by music connoisseurs. When the NBC radio network announced it would premiere a new symphony by an internationally famous composer, therefore, this discussion—once confined mostly to music appreciation books and their critics—spilled out into the open.

These reviews also reveal the degree to which American reactions to Dmitri Shostakovich were refracted through the prism of international relations, colored by deep hostility to Communism as well as deep sympathy for the Russian people’s wartime suffering.[48] Interwoven with the politically-charged commentary on Shostakovich were older beliefs about essential Russianness that musicologists, educators, and critics routinely deployed when analyzing Russian and Soviet music. Such attitudes were on full display in 1942 when Time characterized Shostakovich as a product of both Russia “of the Tsars, of Byzantine ritual, of mad monks and Cossack whips, of fatalistic chaos and fatalistic inaction” and Russia “of the proletariat, of modern industry, of determined socialistic dictatorship.”[49] And such attitudes continued to shape Western discourse about Shostakovich’s music until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989. How ironic, then, that the Leningrad is now a concert-hall fixture in the United States, occupying the same place in the modern canon that the defenders of good music once reserved for exclusively for Beethoven, Brahms, and other Western European composers.

[2] For a detailed discussion of the battle royal among Toscanini, Koussevitsky, Stokowski, and Rodzinski, see Joseph Horowitz, Understanding Toscanini: A Social History of American Concert Life (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1987), 174-77.

[3] “Premiere of the Year,” Newsweek, 20 (July 27, 1942): 66.

[4] For a lengthy discussion of Adorno and music appreciation, see Horowitz, Understanding Toscanini, 189-223.

[5] Percy Goetschius, Masters of the Symphony (Boston: Oliver Ditson Company, 1919), x.

[6] Ibid, 2, 7.

[7] Ibid, 87.

[8] Arthur Elson, The Book of Musical Knowledge: The History, Technique, and Appreciation of Music, Together with the Lives of the Great Composers, For Music-Lovers, Students and Teachers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1927), 368.

[9] Deems Taylor, The Well-Tempered Listener (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1940), 236.

[10] Elson, The Book of Musical Knowledge, v.

[11] Oscar Thompson, How to Understand Music (New York: Dial Press, 1935), 567-68.

[12] Hazel Gertrude Kinscella, Music on the Air (New York: Viking Press, 1934), 5-6.

[13] Walter Damrosch, Instructor’s Manual for Music Appreciation Hour, 1931-1932 (New York: National Broadcasting Company, Inc., 1930), xv.

[14] Schima Kaufman, Everybody’s Music, (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1938), dustjacket.

[15] Sigmund Spaeth, Great Symphonies: How to Recognize and Remember Them (New York: Garden City Publishing Co., Inc., 1936), vii-viii.

[16] Kinscella, Music on the Air, 7.

[17] Theodore Adorno, “Analytical Study of the NBC Music Appreciation Hour,” The Musical Quarterly 78 (Summer 1994): 332.

[18] The C.E. Hooper Company, founded in 1934, was the first research firm to measure the size of radio audiences for specific programs; the AC Nielsen Company followed suit in 1942.

[19] Kinscella, Music on the Air, 8.

[20] Charles O’Connell, The Victor Book of the Symphony, Revised Edition (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1941), xx.

[21] Gerald Abraham, On Russian Music (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939), 243-44.

[22] Gerald Abraham, Studies in Russian Music (London: William Reeves, 1935), 8-9.

[23] Walter Damrosch, Instructor’s Manual for Music Appreciation Hour, 1930-1931 (New York: National Broadcasting Company, Inc., 1930), 16.

[24] Damrosch, Instructor’s Manual for Music Appreciation Hour, 1930-1931, 13-24.

[25] Daniel Gregory Mason, From Song to Symphony: A Manual of Music Appreciation (Boston: Oliver Ditson Company, 1924), 216-18.

[26] Goetschius, Masters of the Symphony, 290.

[27] Downes, Symphonic Broadcasts, 8.

[28] O’Connell, The Victor Book of the Symphony, 337.

[29] O’Connell never acknowledged that Prokofiev made several contributions to the “industrial realism” genre of the 1920s, most notably his 1925 ballet The Steel Dance.

[30] O’Connell, The Victor Book of the Symphony, 367.

[31] Olin Downes, “Two Russian Composers: Comparing Stravinsky and Shostakovich—Their Music and Careers,” The New York Times (February 10, 1935): VII:7.

[32] For more insight into why Pravda denounced Lady Macbeth of Mtsenk, see Elizabeth A. Wells, “The New Woman: Lady Macbeth and the Sexual Politics of the Soviet Era,” Cambridge Opera Journal, 13:2 (July 2001): 163-189.

[33] Harold Denny, “Soviet Denounces ‘Leftism’ in Music: Shostakovich, Once Hailed as Favorite Living Composer, Is Dashed into Disrepute,” New York Times (February 15, 1936): 17.

[34] “Soviet Direction in Music,” The New York Times (April 5, 1936): IX:5.

[35] Olin Downes, “Changes in the Soviet: Shostakovich Affair Shows Shift in Point of View in the U.S.S.R.,” The New York Times (April 12, 1936): IX:5.

[36] “Musical Art Quartet Plays at Town Hall: Shostakovich’s Work Has Its First American Performance,” The New York Times (December 3, 1940): 30.

[37] Howard Taubman, “Records: Shostakovich,” The New York Times (February 1, 1942): IX:6.

[38] “Text of Wallace’s Pledge of Friendship to Russia,” The New York Times (November 9, 1942): 9.

[39] Ibid.

[40] “U.S. Hears Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony,” Life 13 (August 3, 1942): 35-36.

[41] “Shostakovich and the Guns,” 55.

[42] B.H. Haggin, “Music,” The Nation 155 (August 15, 1942): 138

[43] Olin Downes, “Essence of a Score: Toscanini’s Treatment Casts New Light on Shostakovich Seventh,” The New York Times (October 18, 1942): VIII: 7.

[44] Francis Perkins, “Shostakovich War Symphony Cheered Here Under Toscanini,” New York Herald-Tribune (July 20, 1942): 2.

[45] Robert Simon, “Musical Events: Sounds in Summer,” The New Yorker 18 (August 1, 1942): 53.

[46] “Shostakovich and the Guns,” 53.

[47] Ethel S. Cohen, letter to the editor, The Nation 155 (August 29, 1942): 80.

[48] For a historiographical essay on Shostakovich scholarship in the 1970s and 1980s, see “Introduction,” in Laurel Fay, Shostakovich: A Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 1-7. Richard Taruskin’s essay “Shostakovich and the Inhuman” interweaves analysis of Shostakovich’s prominent Stalinist-era works—Lady Macbeth of Mtensk, The Limpid Stream, the Fifth Symphony—with lengthy critiques of earlier scholarly analysis. See Taruskin, Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutic Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 468-544.

[49] “Shostakovich and the Guns,” 53.

See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Knoxville News Sentinel; July 19, 1942, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons