—“Escape Velocity: Fun and Games,” NASA

at 100,000 feet per second while the sun and the earth and all the planets in the solar system whirl around the center of the Milky Way at incredible speed Even this, our galaxy among its cluster of galaxies, moves through space, sliding toward a central point. It is a wonder

of gravity that keeps us “on the ball” even as its thrown and kicked and batted about. How we can’t feel any of it. I used to tell my son we can’t move forward while staring through the rearview. But that doesn’t keep us from trying,

does it? It’s not just where we’ve been or who we were back there and then but how far how

fast, speed a matter of time and distance and how we move

through it. It is hard not to think

we abandoned you back there in that bed, your head titled up as if to see the stars, your mouth

agape. And I think of that last year and how slow each day seemed. Another fall, another bad report from the doctor. Your days got shorter. We ran through every option until there were none left. In hindsight, it all seemed to happen with terrible speed. Each minute seemed a lifetime. And since you’ve gone it’s been all

acceleration. I’m reminded of that trip we took to Florida, I was only eight but I remember playing at the water’s edge with my sisters, delighted by the undertow, planting our feet and plunging our fingers in the sand as the ocean pulled us out, so we could see

You were like that back then, always in a hurry to get to the next place. Ahead of traffic, ahead of the crowd, before the credits began to roll and the last note played out on the soundtrack, first one to the field before the game, first of your siblings to your father’s grave. It was all hurry up

and wait. Which is why you loved to drive your cars to death from highway to highway, Atlas on your knees or spread across the wheel as we all dreamed, fitful, streetlights sliding across our faces. There is power

in movement, in seeing how far you can get in a day. And everywhere you went we followed.

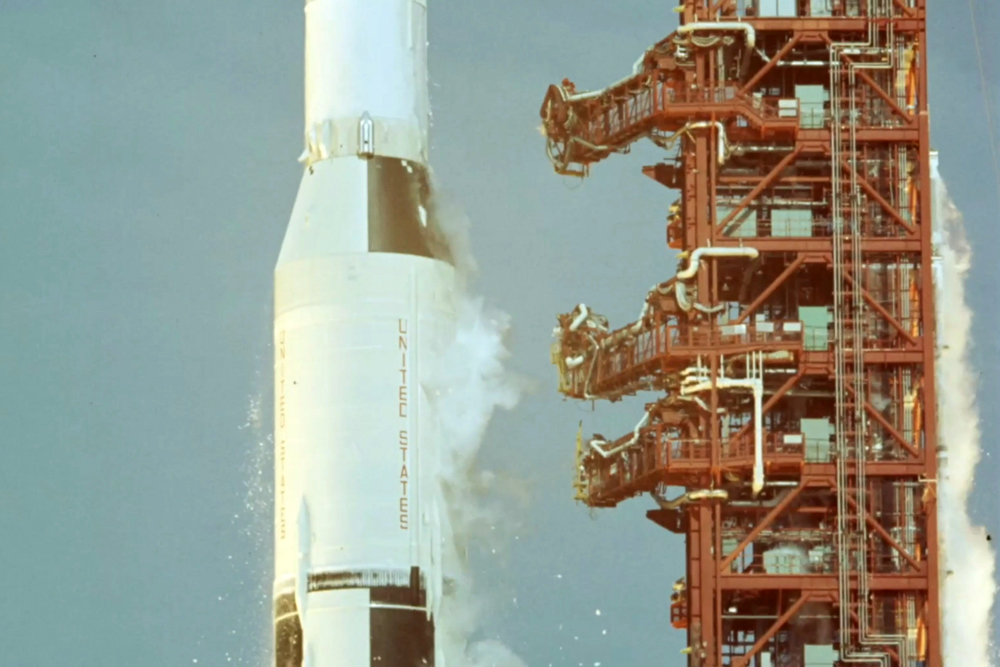

It takes an enormous amount of thrust and speed to break away

from the pull of the earth, to send a body aloft at 36,000 feet per second, but what child launching balls toward distant fences or standing beneath the sun, glove shielding his eyes, head starting to spin, didn’t dream

of rockets back then? Especially you, who raced through life, reckless, always the child charging toward the line of his friends. Red rover Red rover, send Joel on over but you never waited for the couplet to complete, always

already heading straight for the biggest boys on the chain, light but quick with no hesitation, ready to bow, bend, break those links or take them with you to the ground in a heap. I imagine

and apricots—and one day driving back to San Diego State the Van gave up, the engine finally quitting on a hill overlooking a green valley and you found a phone at a gas station and soon your cousins were there pushing the van up and over

the top of the hill as you steered, and you remembered them jogging and laughing behind you, collapsing to their knees and waving their hands as you coasted away “we rolled half a mile down that mountain, right into the service station” you said, eyes still lit

with wonder. “My aunt paid for a brand new engine.” And it was a wonder to watch you stare off and through the walls of the house, a man who couldn’t remember how old he was or who was president or if he’d eaten breakfast. But could remember the Apricots, the sunlight filling the windshield, the pull

of gravity.

The question is not how to write the story of your life but why

I am compelled backwards to a world before me. As if that darkness could explain the one that you are in, and I am speeding towards

you in both directions.

I’ve been a songwriter, vocalist, and guitar/bass player most of my adult life. Recently, I have been trying to bring my different creative endeavors together. The poetry and the music here are my original work. The music and backing vocals are performed by the author. The background archival audio comes from the original flight recording of the Apollo 8 mission and is in the public domain as is the video.

I’ve been writing poems for some time now for a collection titled, Any Moonwalker Can Tell You in which I employ the moon landings and the space program of the 1960’s and 70’s more broadly as a metaphor for examinations and explorations of mortality, isolation, loneliness, memory, identity, and our existential condition. As my father’s health went from bad to worse over the past year, first with rapid deterioration of his memory due to Alzheimer’s and then cancer, the poems began to address his condition more and more directly. He passed this last December in a hospice facility.