We are just now at the beginning stages of what some are already calling the Third Reconstruction. (The second Reconstruction, on this reckoning, began with President Truman’s integration of the US Army in 1948, and ended twenty years later with the repudiation of the Great Society and the triumph of the Southern Strategy in the 1968 election.) We do not know how Lincoln might advise us in the Third Reconstruction because he did not live to see the first one. None of Lincoln’s wartime measures about reconstruction provide much guidance about his postwar policies because those measures were designed to respond to wartime necessities, not to preserve or transform the postwar republic. But we do know how he stood about some of the racial politics that our day shares with his. And knowing how he proceeded may help us know how to proceed now.

During the Civil War, Lincoln supported recognizing new state governments in the rebelling states on relatively easy terms, requiring for instance only ten per cent of the 1860 population to take an oath of loyalty to the United States before initiating the process of setting up a new administration. Lincoln did this to weaken adherence to the Confederacy, particularly in states that had large populations of Unionists, by making it easy for Unionists to take power and for wavering supporters of secession to rethink their loyalties.

After Appomattox, those considerations would no longer have been in play, and Lincoln would have had to design new policies, focused, first, on securing the victory of the United States and making sure that the elements that had almost destroyed it would not be able to threaten it again, and second, on remaking the political, social, and economic order, especially in the South (but not only in the South) in ways that reflected the insights gained through bloody sacrifice during the war. We do not really know what Lincoln’s postwar policies would have been. We know that he opposed the expansive idea of Reconstruction articulated in the 1864 Wade-Davis bill, but that seems more likely to reflect his sense of wartime necessities rather than his settled policy about reconstruction. We also know that beginning in 1862 he was pressing the Unionist rump government in Louisiana to abolish slavery in the regions of the state not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation, to expand rights for the formerly enslaved, and to prepare educational institutions as part of “some practical system by which the two races could gradually live themselves out of their old relation to each other, and both come out better prepared for the new.” In addition, we know that he also pressed Louisiana to grant at least some of the formerly enslaved voting rights, and that in his last public speech a similar call for voting rights moved John Wilkes Booth, who was in the audience, to re-start the conspiracy against Lincoln that he had before that time placed on the shelf.

Beyond this, we know that Lincoln argued that the Emancipation Proclamation was necessitated by the need to recruit Black soldiers into the Army, and that Lincoln understood that military service to the res publica obligates it to grant those who serve it a place in the public sun. The principal argument he used for the Emancipation Proclamation, this is to say, makes an tacit but powerful case for expanded suffrage across racial lines. In a public letter to James Conkling, who was organizing a Unionist gathering in Illinois in August 1863, without explicitly promising the vote to African-Americans who served in the military, Lincoln defended the Emancipation Proclamation in terms that implicitly recognized the claim of Black soldiers to the right to vote, contrasting the steadfast loyalty of the Black soldiers with the questionable loyalty of those white men who, although nominally supporting the Union, grudged Lincoln the means of saving it:

In the struggles after Lincoln’s assassination between Andrew Johnson and Congress over Reconstruction each side could make a plausible claim to speak for Lincoln, and to this day it is uncertain just what course he would have taken. Perhaps he would have foundered in the political cross-currents of that era. But he could hardly have managed it worse than Johnson in fact did. We do not really know whether Lincoln would have stood with the moderates or with the radicals in the Reconstruction Era. We have good reason to suspect that he would have stood firm about his promise of the political rights of citizenship. Beyond this, we cannot say whether social equality was in his mind, because he always preserved deniability about that aim. And we can be relatively certain that economic equality was beyond his reach, even had he wished it, because the economic and policy machinery required to secure that was not within the horizon of his economic thought.

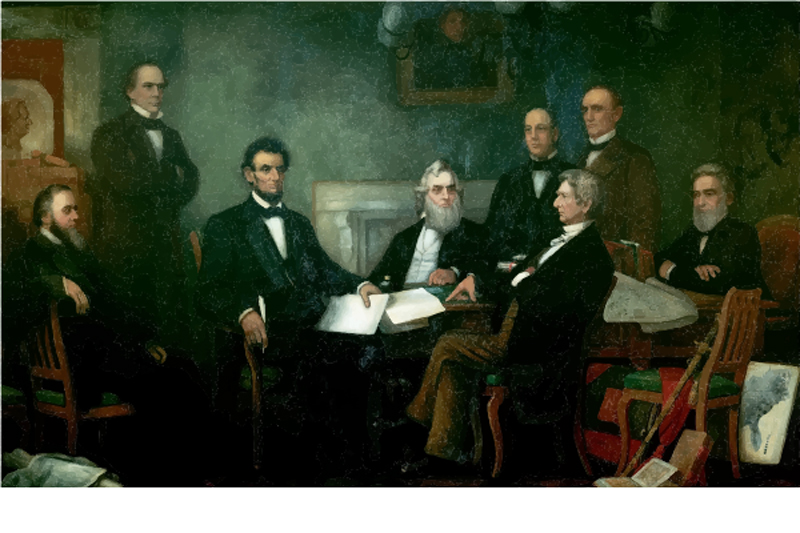

So indirect and so cautious were Lincoln’s moves in the direction of emancipation that he could, in the summer of 1862, while the draft of the Emancipation Proclamation was actually in his desk waiting for a military victory to provide him the occasion for releasing it, write to Horace Greeley a letter which, without actually telling a lie, was calculated to give the public impression that he was not planning to liberate the enslaved people of the Confederacy. We know how the Emancipation Proclamation came about, and we have no reason to doubt Lincoln’s own account of it in the Hodges letter. But even so, it is still an open question how much Lincoln’s thought evolved on emancipation and how much what he did was the result of the careful cultivation of possibilities he had long had in the back of his mind. But perhaps that’s what evolution of thinking really is, the coming to full awareness of things that have always been, somehow, in the back of one’s mind, the following out of implications implicit in one’s values that one has not acknowledged, or been in a position to acknowledge, until the present.

It is possible to trace in Lincoln’s public acts between 1862 and 1865 the same cautious, indirect, always-plausibly-deniable movement in the direction of granting political rights to Black men that characterized his earlier campaign for emancipation. As in the case of emancipation, it is not clear whether one should describe this as an evolution of Lincoln’s thinking or just as his plodding but painstaking working out of the consequences of a commitment he had already made. If his earlier campaign against the extension of slavery into the western territories was a plausibly-deniable way to attack slavery, so his campaign to provide mere emancipation from slavery can also be seen as a plausibly-deniable way to establish political equality. And beyond mere political equality is social equality, a goal Lincoln always denied seeking, but which seems implicit in his pursuit of political equality, since political equality is rooted in the idea of the equal dignity of all persons. We do not know how far Lincoln would have gone, and he worked very hard to keep us from knowing, because had the public known where he was going about emancipation, they would have foreclosed it, and whatever his thoughts about civil rights and citizenship rights for Black people were, they would have faced similar headwinds.

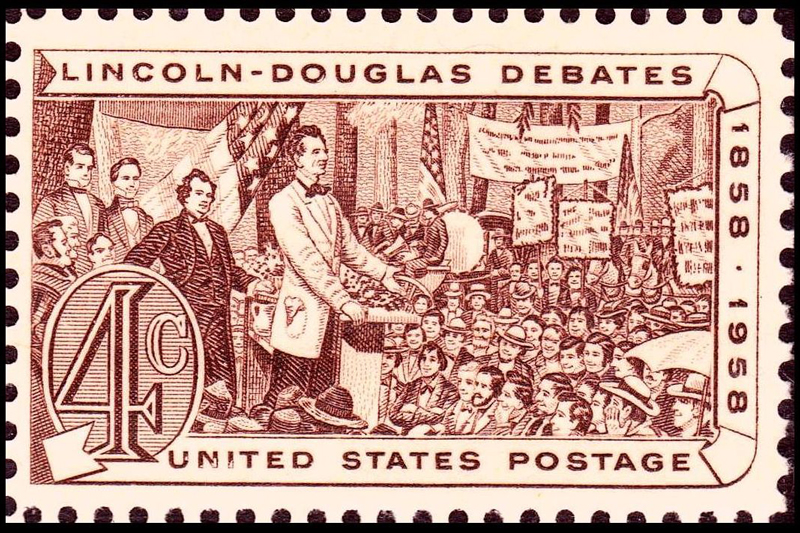

We do not have good evidence about what Lincoln really thought about race. We know that he admired his “good friend Frederick Douglass,” and had Douglass visit him in the White House, keeping some white dignitaries waiting; we know also that he was especially eager to hear what Douglass thought of the Second Inaugural Address from his own lips. But what one thinks about Frederick Douglass and what one imagines about Black people more generally are different things. We know that he was not above casually racist remarks and mortifying statements, such as the bizarre monologue he delivered to a delegation of Black clergymen in the summer of 1862 about colonization (again while the Emancipation Proclamation was already in his desk). On the other hand the small number of Black people who knew him well say that he was comfortable with them and friendly. Many racists, however, and indeed many slaveholders, could have had the same things said about them concerning their relationships with Black people as individuals. We know that in the Lincoln-Douglas debates and after he repeatedly denied seeking political equality (much less social equality) for Black people, but in those circumstances saying anything different would have foreclosed him from doing anything to advance emancipation, never mind racial equality. We know that he proposed fatuous schemes for voluntary colonization (though he never favored forced deportation) of free Black people in Liberia and elsewhere, such as the ı̂le des Vaches in Haiti or Chiriqui in Panama, but he was always aware that colonization was a practical and moral impossibility, and most of what he did and said on this subject seems to have been strategic indirection designed to keep critics of emancipation on their back foot.

Lincoln’s indirection here puts me in mind of the story Roger Wilkins tells about Lyndon Johnson: late in his administration, Wilkins asked Johnson how he, who had baited race with the best of Texas populists, and who had long been a protege of Richard Russell and other segregationist Senatorial leaders, came to be the President who used his muscle to write the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act into law. “Son,” Johnson is said to have replied, “now that I’m President, I’m free at last, free at last, thank God almighty, I’m free at last.” Johnson’s example shows that it is policy, not feelings, that are the best indicators of where a politician stands on race, and that success in policy requires the politician to be, as Machiavelli says, as much fox as lion. And Johnson’s example also shows that racist habits of thought and speech are no impediment to acting boldly for racial equality.

We do not know whether Lincoln would have arrived at the policies he was moving towards when he died, or whether, like so many of his generation, he would have lost his nerve and retreated. The disheartening 1876 Supreme Court decision in United States v. Cruikshank, which held that the federal government was powerless to intervene if armed mobs of racists, with tacit support from their state governments, suppressed civil rights with murderous force in the former Confederacy, was decided by justices who had been appointed by Lincoln and Grant. (Indeed, the one Buchanan holdover, Nathan Clifford, dissented.) But we do know that whatever Lincoln’s racial prejudices may have been, he rejected the most powerful racist political themes of his time and ours.

In his classic The Black Image in the White Mind (1971), George Fredrickson described what, following Pierre Van den Berghe, he called herrenvolk democracy. The term describes a densely-tangled complex of class and racial themes, held together as much by shared resentments and fears as by shared loyalties and values, in which appeals to race loyalty are used to regulate class conflicts among white people. For the rich white, herrenvolk democracy enables the use of racial appeals to blunt appeals for class equality; for the poor white, herrenvolk democracy enables the use of racial appeals to demand solidarity and recognition across class lines. The ability to hold a common front against subjected Black people provided these two groups with the only way they felt they could safely share a republic with each other; under other circumstances, each was a danger to the other. The poor whites could be safely granted a say in the Republic, because the subjection and oppression that would otherwise have been their inevitable fate had been shunted onto Black people. But to enjoy that say they had to make sure that the people who were to pay the price of their freedom paid it in full. (The grim story of how this came about is the burden of Edmund Morgan’s classic 1974 text about the ordeal of colonial Virginia, American Slavery, American Freedom.) South of the Mason-Dixon line (New England was a little different), slavery and democracy were not contradictory values, because only slavery made democracy imaginable. That is how, in Samuel Johnson’s phrase about the American revolutionaries, the “loudest yelps for liberty came from the drivers of negroes.”

Herrenvolk democracy is unstable because the poor whites know that the recognition they are offered is inauthentic, because they know it has its origins in a desire to manipulate their resentments; they know also that the recognition they demand from the rich whites is inauthentic because it depends upon a concealed threat (recognize my equality as a white person or I will be a threat to you). By the same token the rich whites know that their alliance with the poor whites is unstable because the poor whites are always on the lookout for defections on the rich whites’ part, and because the poor whites also always remain dimly aware that their alliance with the rich whites might not finally actually be in their interest. Each side has an interest in stoking hatred of Black people, because it is their chief way of allaying their justified suspicions of each other. But ultimately no amount of racial aggression can quite succeed in removing the poor whites’ suspicion that the rich whites do not in the final analysis really regard them as equals.

Poor southern whites, especially those from Appalachia, tended to support the Union during the Civil War, but frequently their racial views were harsher even than those of the slaveholder class, since the slaveholders often perceived themselves as leaders of what Eugene Genovese called a patronage economy, but the non-slaveholders thought of slaves only as instruments of their masters’ power over themselves; the master class was used to hierarchy and comfortable with it, but nonslaveholders could only adopt racial inequality if they conceived of Black people as somehow less than human. More than sixty years ago C. Vann Woodward’s classic, The Origins of the New South described how, during Reconstruction and after, political leaders of poor whites would make halting attempts at a cross-racial alliance, only to be stampeded by their Bourbon opponents into racial panic. Indeed, as Woodward pointed out, the small number of Black voters who remained on the rolls after Reconstruction, knowing whose anger was most dangerous to them, provided the balance of power that kept the Bourbon “Redeemers” in office; only with the victory of the populist revolution in the 1880s and 1890s was the disenfranchisement of Black voters in the South completed. The most viciously racist of the demagogues who ruled the South until the Second World War were always those with a populist rather than with a Bourbon agenda.

The end of slavery, and even the end of formal legal segregation, left intact the grievances and fears which drove herrenvolk democracy and gave the current politics of white resentment its shape. It plays out nowadays as strongly in the northern suburbs as in the southern town, and it is also nowadays a politics embraced by middle class white people at least as strongly as by poor white people.

Herrenvolk democracy works most powerfully when it is able to focus anti-elite resentment on a cultural outsider. In the mythology about Reconstruction still widely accepted by the public to this day, the Carpetbaggers were more interested in using Black people to advance their own power, seeing them as people they could manipulate and put under obligations to them, than in securing the benefits of Democracy for the formerly enslaved. Further, they also sought (so the mythology goes) to displace the poor white from being an object of public concern and to advance the former slave at his expense.

The intoxicating brew of herrenvolk democracy and anti-elite resentment has been perhaps the most important shaping theme of American politics over the last fifty years. It gave America the politics of “white backlash” encouraged by President Nixon (it was the northern suburban moral equivalent of the “southern strategy,” which has turned the south Republican for the last few decades). It underlay both President Reagan’s attack on “welfare queens” (look at these Black people who are being enriched at the expense of the white working man), and his attack on taxes (since “wasteful domestic spending” is in the populist imagination by definition the spending of money on Black people, money taken, so they imagine, mostly from white people). That a self-proclaimed progressive elite sought to advance Black people at the expense of non-elite white people was the motivating suspicion behind the attacks on “affirmative action” that polarized the politics of the 1980s and 1990s. It is not a stretch to argue that underlying conservative hostility to federal support of health care is hostility to spending money on Black people, even though it would seem obvious that most of the money America would spend on health care would be spent on whites.

No politician recently has used the theme of white resentment as effectively as Trump has, because no politician has more successfully tied white resentment to hostility to the administrative class and to hostility to what he portrays as a self-appointed (and mostly white) moral elite of progressive bureaucrats, experts, activists, and do-gooders. When George Wallace in 1968 denounced the “pointy-headed bureaucrats” to whom he wished to “send a message,” he struck a political nerve, but he remained a fringe figure. But now Wallace’s ideas have completely captured one of the two major parties. The effect has been to make an upsurge in public racism seem to be an egalitarian groundswell. Anti-elite resentment makes embracing White Supremacy seem to be the (white) people’s rejection of their would-be moral superiors’ attempts to dictate their lives to them and to police their morals and their language. If you care about racial equality, you obviously lack the common touch; you are a world citizen, but not an American.

Under Trump, herrenvolk democracy has taken an especially sinister turn, since Trump’s defenders and apologists have embraced what is called in far-right circles the “replacement theory,” the theory that an “internationalist”elite seeks to displace the white working class with Black people or with Brown immigrants who will be dependent upon them and whom they can manipulate politically. Such people are what Trump’s advisor Stephen Miller calls “cosmopolitans,” people who are more deeply enemies of American greatness than the intelligence services of a hostile foreign power. (Those two words, “internationalist” and “cosmopolitan,” used to be brandished for coded attacks on Jews, but now they seem to be aimed at white liberals.) In his notorious article “The Flight 93 Election,” Michael Anton, then a Trump propagandist but later an officeholder in the National Security Council, wrote that the “Davoisie” seek “the ceaseless importation of Third World foreigners with no tradition of, taste for, or experience in liberty,” in order to provide for themselves a docile electoral majority and to humble an America they hate. Those “very fine people” who rallied in the interest of what they thought of as Trump’s values in Charlottesville in the summer of 2017 chanted “You will not replace us” (or, sometimes, “Jews will not replace us”), giving an all too concrete an illustration of what Anton’s words mean.

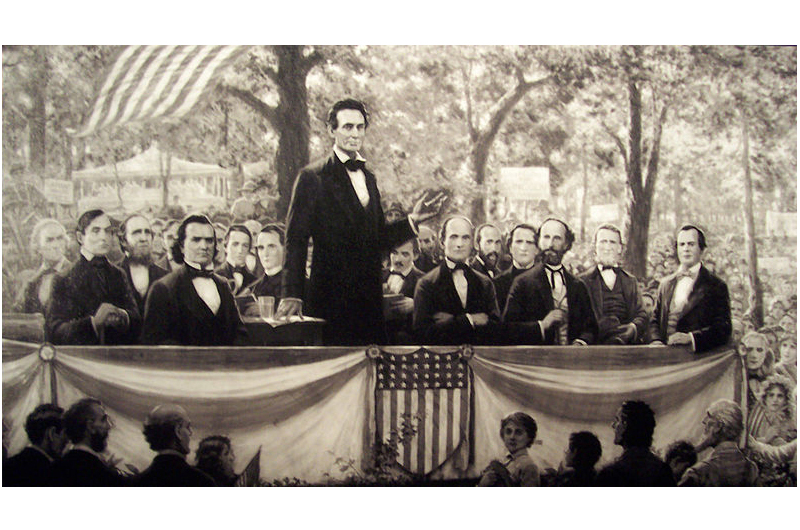

Whatever the state of Lincoln’s feelings towards Black people or his thoughts about their possible futures, Lincoln never showed anything but hostility towards herrenvolk democracy, and to that extent we do know something about what Lincoln would have thought about our present. Anyone who is willing to confront herrenvolk democracy has already made the decision of most consequence about how that person’s racial politics is to be evaluated. Given the power of the herrenvolk-democratic ideology as a driving force in American politics, with its ability to use class politics to undermine and destroy even the most committed attempts to secure racial equality, it will take a politician who can figure out how to defeat herrenvolk democratic appeals to save our republic from the fix it is in now. I do not know whether Lincoln could do that (because I don’t finally know whether it is even possible), but I know that his own humble background gave him some traction against herrenvolk democratic appeals. Lincoln may have hated being called “Abe” and being depicted as a rail-splitter, but he would have faced a different set of political problems had he run as a railroad attorney. On the stump, Lincoln more than held his own against politicians like Stephen Douglas who employed herrenvolk democratic appeals, even in places like Illinois, where such politicians usually carried the day.

Equality has, Lincoln argued, a special, foundational role in democratic political culture. Republics are spaces of self-rule, and self-rule only happens in publics, by which term I mean rule-bound associations of people who recognize each other’s moral equality and agree to respect and conserve each other’s agency, their freedom to act in the public square. You and I inhabit a space of freedom only if we acknowledge each other as equals, only if we see each other as agents whose freedom to act we cannot allow ourselves or anyone else to trample. If I violate (or allow others to violate) the agency of other citizens, I undermine my own.

Now all republics, not just liberal democratic ones, depend upon a culture of equality shared by their stakeholders. But what is unique to a liberal democratic republic, and what, Lincoln felt, American history existed to test the possibility of, was whether the ground of equality was not merely something shared by an in-group of social masters but was something that all people as people might have a claim upon. In the classical world, the clique of insiders, the members of the polis, enjoyed freedom in their relations with each other, but their freedom was made possible by the oppression of the members of the oikos, whose uncompensated labor freed the polis from some of the coercion of biological or economic necessity. The freedom of the Athenian democracy, like the freedom of the slaveholders in the South, was the freedom of a master class, a freedom made possible by the subjection of others. But in Lincoln’s view the American republic had promised that freedom was not merely the privilege of an in-group who could keep others under their heels. The United States was “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” a dedication that required the United States to erase the classical distinction between polis and oikos and to offer political self-rule to everyone.

Lincoln was aware that the expression of newly emerging values was usually halting, and that the people do not often clearly put two and two together about the consequences of their deepest commitments until experience clarifies them. Our central concepts are opaque and general to us until we cash them out in particular conceptions, and those conceptions are always partial and flawed and liable to reconception. Lincoln’s model for this was the promise of human equality articulated by Thomas Jefferson in the opening words of the Declaration of Independence. Unlike John C. Calhoun, who thought of those words as obviously and dangerously false (as “self-evident falsehoods”), or Stephen Douglas, who interpreted them as applying only to white people, Lincoln argued that Jefferson knew very well what the ultimate consequences of the values expressed in those words were, even though he knew his republic, and he himself, for that matter, was neither willing to embrace them immediately nor in a position to make good on them in the near term. He made a promise knowing that it could not be fulfilled when he made it, expecting that time would ripen the opportunities of putting his words into action, and that our Republic would be made unhappy by that promise until it did it better justice. Jefferson’s promise of equality was, in Robert Penn Warren’s pungent phrase, “a burr under the saddle” of America. Even now we do not fully appreciate what Jefferson’s words will finally commit us to, and yet when events shake us awake we trust that those commitments will be clarified in practice.

The meaning of Jefferson’s promises continues to unfold, and their furthest implications have yet to be brought to light. Few of them could have been in the focal consciousness of the Founders. But to deny being bound by the entailments of such values is probably a more destructive misreading of the Founders’ intentions than to acknowledge being bound by them, intentions being complex things. Jefferson, as Lincoln argued, both did and did not will the end of slavery. Lincoln both did and did not will racial equality. Both were in a position to deny embracing those intentions, and their denials may not have been entirely strategic. But both also, in the tangle of intuitions and doubts one finds in the penumbra where human willing happens, what Hannah Arendt calls the chaos of willing and nilling, did indeed will both things, and willed them more deeply than they willed the contrary.

Implicit commitments like these, only darkly understood even by those who made them, have the kind of depth which makes it an open question whether they are something chosen or given, whether they are expressions of conscious agency or the unchosen and inevitable realizations of character and destiny. They are, in Lincoln’s phrase, a proposition a republic is designed to test, but they are also, again in Lincoln’s phrase, a history the republic cannot escape. Only concrete political exigencies force these entailments out of the shadows of latency, where they prepare the way for yet further entailments, unanticipated until they become urgent, but inevitable once they do. It is because concepts are implicit that they become, and it is also because they are implicit that it is only historical experience, not simple rationality, that articulates their becoming.

Lincoln saw America as destined to become an equal multicultural society that will root its sense of being a nation in a common political culture rather than in common blood; he argued that in attempting to become a multicultural, multiracial democracy America will blaze a path for democracy worldwide. Until 2016 it never occurred to me to doubt whether most Americans shared this conviction; now I wonder whether it can even be sustained over the next few years, and I think it may take someone of Lincoln’s stature and insight to save it.

Lincoln presided over the profound economic transformation that he understood would be necessary to win the Civil War, organizing production, overhauling taxation and banking policies, and modernizing distribution. But his own economic ideas were rudimentary. Defeating the Confederacy required all of the economic and organizational resources of an advanced industrial democracy, and although Lincoln and his cabinet made expert use of those resources, Lincoln’s economic thinking remained provincial. Despite working as an attorney for the Illinois Central Railroad, capitalism in Lincoln’s imagination, as Richard White argues, always remained capitalism as it was practiced in the Springfield, Illinois, of his time, a capitalism of small enterprises run by proprietors who were not far different from skilled tradesmen, in which workers could regularly advance into management or into the ownership of their own businesses, the world idealized in the novels of Horatio Alger.

In Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men, Eric Foner ascribed to Lincoln what he called the “Free Labor Ideology.” The contents of this ideology will seem familiar, both in its strengths and in its weaknesses. The idea of self-help and advancement though individual initiative is still an attractive one in America, and with reason. The possibility that one might escape the economic hardships of one’s parents, as Lincoln himself did, has served to justify and stabilize the American republic in just the same way that having an open frontier did in Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous account of it. But like the safety-valve for the pressures of social conflict offered by the frontier, the safety-valve for individuals offered by the free labor ideology was increasingly not the full story as the post-bellum era went on, and it is less so today than it has been at any time since the Gilded Age.

Articulating his economic ideas in speeches in New Haven and Hartford in 1860, Lincoln argued, as Marx did, that labor is what underlies all economic value, and conceded that the worker at the bottom of the social scale is exploited. What he sought from the free labor ideology was not a way to improve the conditions for the working class as a whole but a way for some of the members of that class to escape to another class, a way theoretically open to every individual, but only because there would always be other people, other beginners, starting their progress from the bottom story. The distinction between improving the situation of the working class and providing means for individuals to escape that class was roughly the distinction between nineteenth century Democrats and nineteenth century Whigs. (The nineteenth century Democrats were herrenvolk democrats, but they did know about class in ways the nineteenth century Whigs, of whom Lincoln was one, did not.) Lincoln did not imagine that the United States would ever become a society with a permanent underclass, much less the permanent urban underclass of the Gilded Age. Nor did he imagine a society in which economic and social institutions would systematically limit escape from the bottom levels of society; Lincoln said that the worker who felt his oppression had the option to strike, but he seems to have meant by that word something like having the ability to quit, not the ability to organize a union and hold out for better wages and conditions, something which Lincoln’s successors, with reverence for him always on their lips, ruthlessly and successfully put down with all of the armed force available to them.

Nor did it occur to Lincoln that social advancement might require a complex and expensive institutional machinery to make that advancement possible. All that he felt would be required was freedom, because that was all he himself had had to rely on. Some students of Lincoln’s thought, such as Allen Guelzo, think that he believed that since what was chiefly wrong with slavery was its repression of the slaves’ ability to advance their status by their own wits and efforts, emancipation itself would open the door to equality. This idea looks hopelessly naive to most people now. But it was a widespread idea in the nineteenth century. Frederick Douglass believed it too. It is a common assumption about Reconstruction that the only reason it failed was because the white Northern politicians whose support made Reconstruction possible either lost their nerve, or surrendered to their own racism, or, confronting a different from of “the other” in the form of the immigrant from southern or eastern Europe, came to sympathize with the southern white’s own fear of their different “other.” But it is also likely that Reconstruction failed because even its supporters, spellbound as they were by charismatic economic superstitions like the Gold standard, did not have the political imagination to create the economic and political institutions that would have been required for it to succeed, institutions that only came into being during the Depression. (It remains to be seen how many of our own contemporary economic ideas are rooted in similar superstitions.)

Many forward-thinking figures, such as Albion Tourgee, understood that the project of political equality was a hopeless one unless both the white and the Black South could be lifted out of poverty by economic modernization, but the economic modernization they had in mind consisted chiefly in employing the laissez-faire methods later adopted during the period of the New South. These involved embracing industrialization, which they could make succeed by undercutting the Northern manufacturers by offering lower wages and fewer worker protections, a strategy which wound up embittering rather than softening racial conflicts, since factory owners used the threat of employing Black labor to keep white workers in line, in an all too literal version of the “replacement theory.” Only a few understood that tenant farming on the crop lien system (never mind sharecropping) would never result in anything other than the increased impoverishment of those caught up in it.

Even those who understood that the formerly enslaved could not be simply cast out without resources or recourses into the midst of a society of people who hated them, who understood that it would be a considerable task to transform the Southern economy and political culture, sought to do necessary but not sufficient things, such as to build public schools in the South (which the Redeemers either closed or underfunded as soon as they restored White Supremacy). Even those who sought to distribute slaveholder land in the form of the famous “forty acres and a mule,” underestimated the magnitude of the task. Is it likely that the formerly enslaved, without price supports, without credit, without public regulation of markets, without all of the agricultural social infrastructure that only came into being during the New Deal, would have fared any better than the Homesteaders did? Add to this the likelihood that such a course would have provoked such a violent reaction from the white South that the wave of lynchings and repression that brought down Reconstruction would have seemed small in comparison.

One of the many ironies of southern history is that the progress towards racial equality that was made during the Civil Rights era could not have been possible had not the New Deal lifted the white South out of its dire poverty, yet the New Deal itself was possible only insofar as its proponents were able to avoid offering any challenge to Jim Crow: without the New Deal’s blind spots, no economic revival of the South; without the economic revival of the South, no Civil Rights movement.

Although I do not think Lincoln’s economic ideas would have proven adequate to the challenge of Reconstruction, there is still a crucial difference between his Whig economic ideology and the ideology of postwar Republicans. In Daniel Walker Howe’s account of them, the Whigs, like the Republicans, were a business-oriented party, but they understood that orientation in a slightly different way from their successors. The Whigs represented a nascent capitalism that needed nurturing and public investment; their kind of capitalism claimed to be rooted in a public-minded ethos of noblesse oblige and mutual obligation, and in a moral world in which people gradually master habits of restraint and foresight, rather than a capitalism rooted in “survival of the fittest” in which rules and duty are for losers. They supported public investments such as improvements to rivers and harbors, public roads and canals, public universities, and distribution of public lands, and were associated with a host of reforms aimed at making society better capable of caring for its vulnerable: temperance first of all, but also reform about the care of the mentally ill, a more nurturing style in educational institutions (linked to the idea that teaching might be a profession for women). They had a taste for generally improving institutions such as lyceums, Sunday Schools, and benevolent societies. They liked public-private partnerships, but the use of public-private partnerships during the Gilded Age by the builders of railroads (in order to loot the public treasury and to subject the farmers who would become dependent upon those railroads to bring their crops to market) seems more a perversion of their values than an expression of them.

The key difference is that antebellum Whigs like Lincoln did not imagine their world in the social-Darwinist terms that Gilded Age Republicans did. They may have aligned themselves with Adam Smith, but they did not align themselves with Herbert Spencer. They did not see the manufacturer as a successful apex predator who has clawed and bitten his way to the top of the ecosystem, but as a benign servant of the public good. Lincoln would never have embraced the views espoused by the Gilded Age Yale sociologist William Graham Sumner, whose 1883 What Social Classes Owe to Each Other argued that the rich essentially owe nothing to the poor, who deserve their fate and whose subjection is the price of all public progress.

Nineteenth century Manchester may have had its Bounderbys, and may have found its vision of the economic world as red in tooth and claw to be somehow bracing, but antebellum Lowell tried to imagine itself as a kind of utopian community. Lowell did not turn into Manchester despite itself just because its factory owners were hypocrites but because even the best of them did not understand the genie they had summoned out of the lamp. Had he lived, Lincoln would most probably have been among their number, tied to but not quite one of the Robber Barons and other would-be ubermenschen who came to rule the last third of the nineteenth century in America.

The legacy of herrenvolk democracy plays out strongly in issues that on their face do not seem to be racial at all. A classic 2001 paper by economists Alberto Alesina, Edward Glaeser, and Bruce Sacerdote asked why the United States has not developed a European-style social welfare system. The main driver seemed to them to be racial politics. Alesina and his colleagues’ research suggests that the two great domestic issues in American politics, racial equality and social insurance, are in conflict with each other, since efforts to increase racial equality also increase resistance to social insurance, and attempts to increase social insurance run afoul of racial resentment. Franklin Roosevelt, one might argue, was able to advance social insurance because he was extremely cautious about racial equality. Using the same logic one might argue that Lyndon Johnson, seeking to embrace both things, soured the white vote on both of them. The same logic suggests that one reason why the Affordable Care Act was so unpopular with people it was designed to benefit, white working class people, was that the politics of social insurance lead white people to give up benefits rather than share them with Black people.

The Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam in 2007 published a study in which he showed that in diverse communities social trust and social engagement diminishes in proportion to the diversity, reducing social solidarity and social capital. “The effect of diversity,” Putnam writes, “is worse than had been imagined. And it’s not just that we don’t trust people who are not like us. In diverse communities, we don’t trust people who do look like us.” Putnam’s argument might suggest that the hostility to increased immigration of “those people” we have seen among Trumpists may be a rational reaction to a real problem, since there is a social and political price to pay — the decay of organic community — for ethnic diversity. However, as far as the United States is concerned, the choice about ethnic diversity was irrevocably made generations ago, and in point of fact groups that were long stigmatized as being incapable of incorporation into the body politic, beginning with the influx of immigrants from Ireland at the time of the potato famine (the original impetus for nativist politics in America), are now integral parts of the American political order, leaving the United States with the choice either of increasing social solidarity in the face of diversity by finding ways to increase inclusion, or of descending into becoming a society of resentful winners and resentful losers.

A new consequence in our day of the politics described by Alesina and his colleagues is not merely hostility to all forms of social insurance but a systematic withdrawal of sympathy for the vulnerable and the unlucky. The consequence of the common Trumpist belief that others have somehow cut in line in front of them in the queue for the American Dream (to quote the metaphor of Arlie Hochschild in Strangers in Their Own Land) is a sense of being displaced by those who have a lesser claim to public concern than they feel is due to themselves, from which arises a sense of betrayal and woundedness. This narcissist wound limits their compassion to those who share their wound: “Everything that goes to ‘those people’ is taken from me” one might say, “and concern for them is the means the administrative class uses to dispossess me of what is rightly mine.”

Now the principle of insurance is that we do indeed have a stake in each other’s well-being, and that we can each imagine both ordinary and extraordinary misfortunes coming our way. But we can see others’ misfortunes as something that might come to us as well only insofar as we can put ourselves imaginatively in their situation. It is small wonder that Trump’s supporters took positive pleasure in leaving the American citizens on Puerto Rico to flounder and scrape for themselves in the wake of Hurricane Maria. The cruelty is the point, as the columnist Adam Serwer observed.

It isn’t just that there is never enough money to satisfy all the people who have claims on it. It’s that “those people” have harmed my self-possession in the face of the world, and spiting them, and spiting the do-gooders who advocate for them, gives me a little rush of much-needed pleasure at their expense, because it shows the world that I am a tough-minded realist, someone not to be imposed on. When back in 2017 Mick Mulvaney, then Trump’s director of the Office of Management and Budget, was criticized about the possibility that the budget cuts he proposed would close Meals on Wheels programs in certain states, showing no compassion for the people who needed the food, he replied that his budget proposal showed plenty of compassion, compassion for the put-upon people who paid the taxes. Mulvaney articulated with perfect clarity the line of thought I have been developing, and the little smile on his face as he made that point on television spoke volumes.

I used to joke that the reason Capitalism and Democracy so frequently run together is that the business cycle ensures that no ruling party will be able to entrench its hegemony completely. A better version of this argument, and one whose lesson we are perhaps having to learn the hard way as I write this in July of 2020, is that the instability of capitalism causes it to always need rescuing. In America this instability often provokes America to right itself both economically and politically (as Heather Cox Richardson has recently pointed out). So, for instance, the Great Barbecue of the Robber Barons gave us the economic disasters of the 1890s, which brought forth the Progressives whose measures ended child labor, improved working conditions, and introduced reform in public health. The high, wide, and handsome bonanza of the 1920s caused the Great Depression, from which arose the New Deal. One might have expected that the great crash of 2008-9 would have brought forth a similar level of economic and political reform, but that possibility was subverted by the Tea Party victories in the 2010 elections, with the result that we are having to learn those same lessons over again, but this time from a position of far greater weakness.

I have argued that Lincoln’s economic thinking was unequal to the challenge raised by Reconstruction, and probably therefore would be unequal to the challenge raised by the economic collapse we are perhaps in the early stages of now. More than this, because the ability to respond to an economic challenge is itself fettered by racism, which sees every attempt at social insurance as a mere pretext for Black people to freeload, it is all too possible, unless the last few months have shocked a majority of Americans into wakefulness, that the mutual embrace of racism and laissez-faire has locked our Republic into an economic and social death spiral.

Skeptics may have reason to doubt the depth of white revulsion against the deaths of Black people at the hands of the police in the summer of 2020; perhaps they are right that white people are not ready to strike a crippling blow against racism, but wish only to feel that they are a little less complicit in it. But the fact that the looting that followed the immediate protests of the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers did not immediately provoke the white backlash one might have expected, indeed, the fact that the protesters outlasted the looters, gives me some qualified grounds for hope that our Republic may yet find the Archimedean point it can use to lever itself out of the grip of herrenvolk democracy. Perhaps the marriage of convenience between laissez-faire and racism may finally be on the rocks.

The greatest temptation one faces when one writes an article with a title like “What Would Lincoln Do?” is to use Lincoln as a kind of ventriloquist’s dummy in order to have Lincoln lend his imprimatur to views one already holds on other grounds. So the best lessons to learn from Lincoln (whether or not I have in fact learned them) are the lessons about his humility, his generosity, his skepticism about human nature, and his freedom from self-righteousness and cant. These are the lessons of his greatest speech, his Second Inaugural Address.

Describing in his second Inaugural Address the circumstances in which he delivered his first, Lincoln recalled a Washington under the shadow of an impending Civil War which, he said, all dreaded and all sought to avert, though each acted in such a way as to make the devolution of the conflict into war more and more likely:

The key word in the passage is “deprecated,” a complicated word which means, in essence, “professed to oppose war while making it inevitable.” Applied to the Lincoln’s own side, the Unionists, the word can be interpreted to mean “I don’t want war but I’m not afraid of it (and don’t really have the least idea what it’s like).” Applied to the fire-eaters it means something like “I’m a peaceable man, but you don’t want to find out what I’ll do if you don’t give me what I want right now, and you better smile while you are doing it.”

The specific issues over which they quarreled — the organization of Kansas Territory, the fate of slavery in New Mexico, the extension of the Missouri Compromise Line, the Corwin Amendment protecting slavery, the imposition of a federal slave code for the territories — were all false ones, and in retrospect Lincoln was perfectly aware that settling them would merely have postponed rather than settled the conflict. The folly of each side was that each dimly knew that they were ready to spring at each other’s throats, but neither quite acknowledged it, perhaps even to themselves. They each had dark intuitions they were not quite able to keep down but were incapable of facing up to.

At the end of the paragraph, Lincoln waves away whole shelves of nonsense with the blunt, chilling remark “And the war came.” The war itself is the only agent, not the political class on either side, since both groups were driven by urgencies they disowned but couldn’t escape. The war itself was the only party with any honesty about the conflict, bluntly dismissing the entire delusional habit of thought of all of the human agents. That last sentence is pitiless and clear, as if spoken by someone emotionally very far from the events who has seen through all of it.

I have defended Lincoln’s choice in 1861 and 1862 to give defense of the union priority over abolishing slavery, mostly because the former was a precondition of the latter. But Lincoln in the Second Inaugural gives himself no such defense, arguing that everyone, on both sides, knew that slavery, which “constituted a peculiar and powerful interest,” was “somehow” the cause of the war. His own side, no less than the seceders, were in a position to know what the deeper issues were, but disowned that knowledge, and came to blows with each other in a haze of illusion, self-serving, and wishful thinking.

Now the word “peculiar” is used by Lincoln in a very complicated way. In the first place, it means “special and distinctive,” in the way slaveholders meant that word when they described slavery as their “peculiar institution.” Here it refers to a kind of epistemic closure that goes with specialness: for slaveholders, the word meant that their point of view was incomprehensible to those who have not lived it, and cannot be judged by outsiders. For nonslaveholders, the word “peculiar” renders the magnetizing power of the word to distort reality around it, so that within its field things that are wildly abnormal seem natural and even honorable.

“Peculiar” also means “strange” or “mysterious,” as if slavery exercised a kind of hidden compulsion over the national psyche that even those in its grip did not understand, a distorting obsession which mystified and hypnotized the body politic. A peculiar and powerful interest is a fatal but obscure force, unacknowledged and incapable of being resisted or even fully understood. Everyone on both sides “knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war,” but nobody faced up to it, preferring to see the conflict instead as a series of false issues or proxy struggles over the tariff, over states rights, over federal power, over cultural difference. It’s that “somehow” in Lincoln’s sentence that carries all the charge: it describes what one knows-but-doesn’t-know, what one denies and disavows but clutches tightly in secret. (This is still how all too many Americans think about the origins of the Civil War.)

Both sides were the prisoners of folly, a folly rooted in an underestimation of that “somehow,” a folly that enabled them to hide from themselves the gravity of slavery, and to minimize the compulsive force slavery had over all of their minds. The war was itself was conducted in the same fog of illusion and wishful thinking in which it began:

Lincoln is particularly harsh on the idea that any side has the right to call in God as an ally, even if they have reason to believe that they are right about the immediate issue:

Right now I confess to a very deep anger with my countrymen. Many of Trump’s supporters were energized and uplifted by his racism and xenophobia. They felt the thrill of being able to throw off restraints, to speak unguardedly things that burned in them that both parties had tried to suppress, and to cheer on the ugliest acts our government could contemplate doing. And they have unreservedly enjoyed, have taken deep, soul-satisfying pleasure, in every ugly act Trump has done since coming to power. They defended him when his agents took young children from the arms of their mothers at the border and threw them both into separate forms of confinement, making no particular effort to keep track of where they had been sent, and leaving the ultimate reunion of parent and child to be managed by others. They gleefully embraced the prospect of deporting people who had been brought to America as children and who had even served in our military. They did not raise a peep of protest when Trump betrayed foreign allies who had risked their lives in our interest, or when he winked at the dismemberment of an American-employed journalist at the order of a foreign leader he sought to please. When he abandoned Americans who had suffered misfortune, whether from natural disaster or from the current pandemic, they imagined those who were suffering as whiners who were getting what is coming to them. And so on, down the whole endless list.

So where do we stand now? Our country has betrayed the most important contribution it has made to the moral evolution of world politics. And unlike other periods in recent history, in which the United States has made moral compromises in order to defeat real world threats, this time the United States, with smaller players like Orban’s Hungary, Duda’s Poland, Erdogan’s Turkey, and Putin’s Russia, has itself decided to lead the way down to darkness, to a world driven by ethnic nationalism and authoritarianism. At other times in our history the United States has stood for things progressives in the world have admired, while using means they criticized. This time those who have most admired the United States have most reason to fear it. And now, perhaps most humiliating of all, they regard America as an object of pity.

The lesson of the Lincoln Second Inaugural Address is that people on my side of the fence too share the burden of a history of herrenvolk democracy; it has opened possibilities for us, and it has shaped our political identities in ways we might find hard to acknowledge. Even our own anger with the Trumpists shows us how easy it would be to settle into a politics of resentment and score-settling, a temptation I myself did not fully resist in the previous paragraph. They, too, are America. They too are our countrymen. We can disavow them no more than we can disavow the crimes of our own ancestors, whether genetic ancestors or intellectual and spiritual ancestors, the ancestors who gave us, with all its good and all its bad aspects, our identity as Americans. Trumpists right now are intoxicated by an ugly brew that has gone to their heads. They will need someone to take their hand when they wake up, hung over. And swe have to take responsibility for them the way we take responsibility for the crimes of our ancestors, by recognizing a human fallenness we share with them.

John Burt is Paul Prosswimmer Professor of American Literature at Brandeis University, where he has taught since 1983. At Brandeis he teaches courses on American Poetry and Fiction of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Literature of the American South, Fiction of the Second World War, Slavery in the American Imagination, and the Literature of the Reconstruction Era. He was also for a long time the director of the First-Year Writing Program. He is the author of Lincoln’s Tragic Pragmatism (Harvard) and the editor of The Collected Poems of Robert Penn Warren (LSU). He is also the author of three books of poetry, all with cheerful titles: The Way Down (Princeton), Work Without Hope (Johns Hopkins), and Victory (Turning Point).

John Burt is Paul Prosswimmer Professor of American Literature at Brandeis University, where he has taught since 1983. At Brandeis he teaches courses on American Poetry and Fiction of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Literature of the American South, Fiction of the Second World War, Slavery in the American Imagination, and the Literature of the Reconstruction Era. He was also for a long time the director of the First-Year Writing Program. He is the author of Lincoln’s Tragic Pragmatism (Harvard) and the editor of The Collected Poems of Robert Penn Warren (LSU). He is also the author of three books of poetry, all with cheerful titles: The Way Down (Princeton), Work Without Hope (Johns Hopkins), and Victory (Turning Point).