“Russian soldiers stayed in our building,” the poet Lesyk Panaisuk wrote to me a few weeks ago. When the war began, Lesyk left Bucha in a hurry, fleeing the Russian invasion.

“War will live in Bucha long after the soldiers are gone,” Lesyk emails me, “because they left a lot of mines throughout Bucha.” Now it is dangerous to walk around the town. Lesyk’s neighbors found some mines in the halls of their building, inside their slippers and washing machines. Some neighbors returned only to install doors and windows. “In our neighbourhood doors to almost every apartment were broken by russian soldiers,” Lesyk writes.

This is a window into the horror that is the current invasion of Ukraine: in the middle of the ransacked city of Bucha stands a house whose owners couldn’t return to it for a while, not only because of mines and grenades left by russian troops, but also because of radiation.

Lesyk writes that coming from north of the Kyiv region, some of the soldiers went through the Chornobyl zone and, unfortunately, took some things with them to Bucha (for instance, a flask with radioactive substance stolen from the Chornobyl nuclear plant was found by a Bucha citizen in his household after the liberation). Particles of invisible war keep on living in the rooms of people’s houses even after the soldiers left.

How can poetry describe something like this?

How can any language speak of a country that’s bombarded while the rest of the world looks on?

“A Ukrainian word / is ambushed: through the broken window of / a letter д other countries watch how a letter і / loses its head” writes Lesyk in one of his poems. He continues: “how / the roof of a letter м / falls through”

These days, Lesyk hometown, Bucha, is often shown in the news. “We see our house, our broken windows, dead people,” he writes to me of seeing his own street flash on the TV screen: “dead people, someone was shot in the street, someone was tortured. A man with his ears and nose cut off was found in our complex—he was our neighbor. Graves and dead bodies—everywhere on streets we walked almost every day.”

“Bucha was a city where artists, scientists, doctors lived,” he writes. It was a small, cozy town with a beautiful landscape. People came here looking for a quiet life, they came here to start and raise families. And now I don’t know how to live here and not remember everyday what happened.

“The war is one long unbearable day,” he writes. “It is a day that cannot end: time in war is sewn together from continuous anticipation and constant action. We are waiting for the air raid alarm, waiting for the news from the front, waiting for the opportunity to escape. We write.”

The language in his vivid, image-laden poems, becomes the character, the living being:

“By the hospital bed of letter й

lies a prosthesis it’s too shy to use.

You can see the light through the clumsily sewn up holes

Of letter ф – the soft sign has its tongue torn out

due to disagreements regarding

etymology of torture.”

There is so much pain, in this music of witness, in this surreal—no, not surreal, it is all too real—testimony that is also a dreamscape made by fear and stress and anger. This song that is also a silent scream, an elegy that is also a shout of protest, this love letter to his country that is also a brick tossed at a helicopter. Here, readers, is a poet whose work won’t be easy to forget.

Forgetfulness is unacceptable.

versions from Ukrainian by Ilya Kaminsky and Katie Farris

OUR FACES, TOSSED ABOUT THIS LAND

I

Russian soldiers drop from the sky clinging to parachutes of our faces –

to the corners

of our lips

their fingers

hook.

These parachutes, torn, are no

longer our cheeks

our noses our teeth:

In the mirror

I do not see my face.

They are dropping, they are climbing down the stairs

of the sky.

Our faces, our tornswollen

faces our clattering the earth faces, dirty, our

faces tossed among the shards of this day.

II

Russian soldiers park a tank in our yard

clabber into the apartment

read our books not understanding Ukrainian English

Polish Belarusian Czech Latvian Romanian German

French Georgian Swedish Croatian Turkish Spanish

and even in Russian

Please explain this poem a soldier asks our neighbors

while tossing

them against walls

Asks our neighbors to explain a line break

while raping our wives a third time a fourth time a fifth

asks children

of our neighbors to explain while they are locked up in the basement

Please explain this poem a soldier asks

while our neighbors

are slaughtered

Asks our neighbors to explain a line break

while our children

are without food in a basement

Our faces tremble

As if from the wind

‘How is it’

–a soldier asks—

‘I don’t understand words

if ours is a nation that reads most in the world?’

ІІІ

Russian soldiers are cooking a soup with vegetables snatched from our barns and refrigerators

they are tossing our

books

to light the stove.

Burning are the fine editions of the youngest Ukrainian poets

Then poets of twothousandtwenties twothousandtens ninetynineties ninetyeighties sixties fifties

and so on until the end of Ukrainian literature

burning are translations

and books in original

contemporaries burning and classics

On fire are all the authors who influenced us, fire

coughs on each book we haven’t read

or read or planned to read

burning are our poems published and unpublished unwritten and rewritten

And this poem about our faces

tossed around in the backyard is a flame

so Russian soldiers finally can gulp their soup.

ІV

Russian soldiers decide to entertain

other Russian soldiers by showing off our children’s photo albums

Hey, this one, see? In a bunny costume, an idiot

unlike me here in a military costume

and me again in paratrooper’s costume

and me a sailor

bunnies they are a funny nation

and here he hugs the toy dog just like a girl

but I, yes, I, I had a long sword

and I had a gun

and I ran with a rifle

they these funny people, hug dogs what a strange pictures

hey watch how the fire laughs

And so the childhoods is flames and school years are flames

their charred particles fly up and drop on our faces scattered about in the backyard

V

Russian soldiers are like worms yes like worms they are crawling out from their

black soil of Russia

to die in the puddles of tears on this Ukrainian street

On the airplanes they fly here and on helicopters

they drop here clinging

to parachutes

of our faces –

On the warships they are navigating across the waters of our day

In the sky they are dying in the ground

they are dying in the water

they are dying they

are dying

But no laughter

is heard

No laughter on the lips of our faces which are tossed about in the backyards.

O the accordion of a municipal bus!

your insides

are clattering with our silences which

we take from our apartments to factories and offices and take it

from work

back home

and from home to hospitals and from hospitals to groceries.

Silence is not golden

it is not

golden it is not

at all –

it’s money that costs less than the paper

on which it’s printed. Inflation!

O inflation

we are all of us millionaires, and it costs

us nothing now to

keep

our mouths shut.

Inside this old and dusty accordion of a public bus

we are the musical notes

too rotten

for a hymn.

Silence is our national currency thousand pink tongues pay

for one little injustice.

Our silence lives under the mattresses in bookcases between

pages of books deposited

as bodyfat

in our fingers and cheeks.

The bus driver

puts his index finger to his oily lips.

This bus, this Russian accordion of a bus, where is it

speeding us to

clutching its engine, flapping

its doors

while an occasional spar flies up, it

is as if gunsmith

is playing an instrument of our bodies

about which

we say not a thing.

Lesyk Panasiuk is a Ukrainian writer, translator, designer and performance artist. Author of 3 poetry books (in Ukrainian), books in translation published in Romanian and Russian, individual works translated into 19 languages. Translator and co-translator of books by Valzhyna Mort, Siarhey Prylutski, Dmitry Kuzmin, Artem Werle and 3 anthologies of Belarusian literature. Laureate of various literary contests. Scholar of the President of Ukraine stipend for writers (2019). Resident and scholar of international residences for writers and translators in Latvia (Ventspils, 2019) and Poland (Warsaw, 2021).

Lesyk Panasiuk is a Ukrainian writer, translator, designer and performance artist. Author of 3 poetry books (in Ukrainian), books in translation published in Romanian and Russian, individual works translated into 19 languages. Translator and co-translator of books by Valzhyna Mort, Siarhey Prylutski, Dmitry Kuzmin, Artem Werle and 3 anthologies of Belarusian literature. Laureate of various literary contests. Scholar of the President of Ukraine stipend for writers (2019). Resident and scholar of international residences for writers and translators in Latvia (Ventspils, 2019) and Poland (Warsaw, 2021).  Katie Farris is the author of Standing in The Forrest of Being Alive, which is forthcoming from Alice James Books in 2023. Her previous collection, A Net to Catch My Body in Its Weaving was published by Beloit Poetry Journal as the winner of Chad Walsh Poetry Prize.

Katie Farris is the author of Standing in The Forrest of Being Alive, which is forthcoming from Alice James Books in 2023. Her previous collection, A Net to Catch My Body in Its Weaving was published by Beloit Poetry Journal as the winner of Chad Walsh Poetry Prize.

Ilya Kaminsky is the poet and translator, author of most recently Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press) and Dancing in Odessa (Tupelo Press). He lives in Atlanta.

Ilya Kaminsky is the poet and translator, author of most recently Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press) and Dancing in Odessa (Tupelo Press). He lives in Atlanta.Bodydock, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

EnergyButterfly, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

EnergyButterfly, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

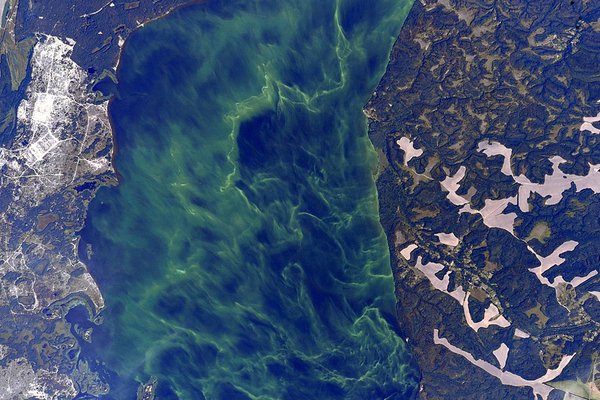

NASA/Kjell Lindgren, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

EnergyButterfly, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

EnergyButterfly, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Михайло Пецкович, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Medoffer, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Mykola Swarnyk, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

EnergyButterfly, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Guillaume Speurt from Vilnius, Lithuania, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons