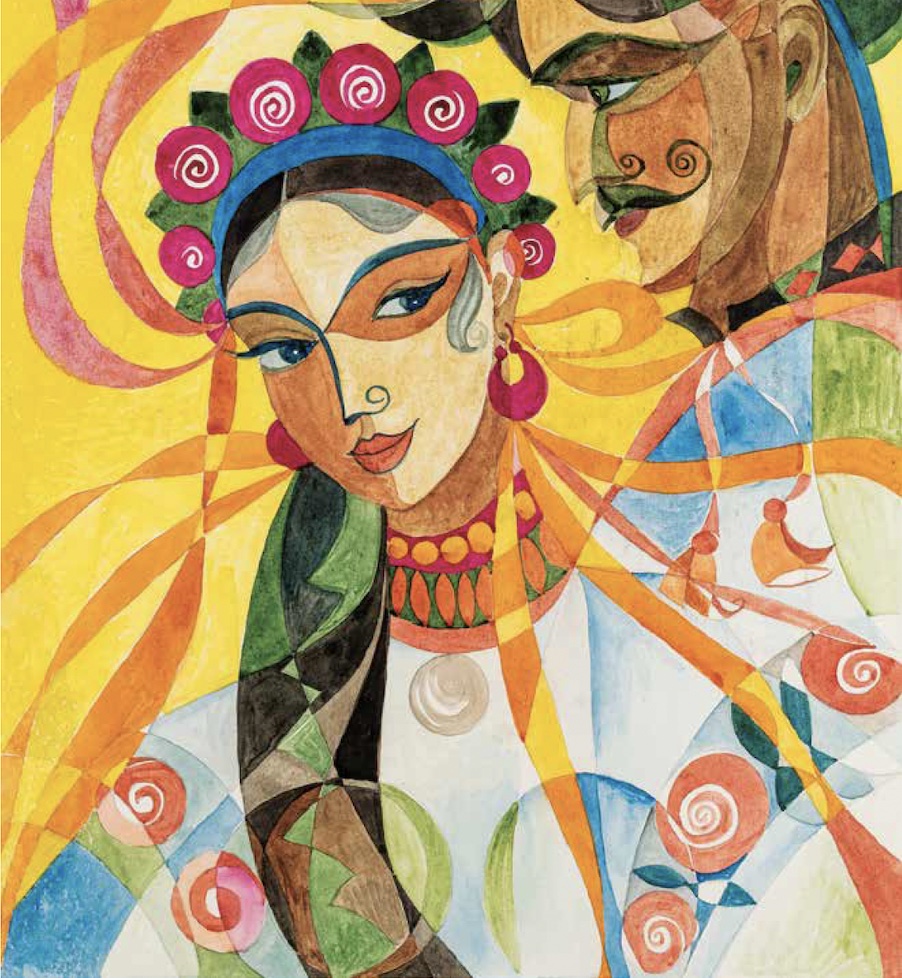

This fictionalized short story is dedicated to the memory of Ukrainian artist and designer Liubov (Luba) Panchenko, who endured a month of isolation and starvation in her basement while her hometown of Bucha was under brutal Russian occupation. She survived the occupation, but died on April 30, 2022, when her heart gave out. During the Soviet era, her artwork was censored due to its focus on Ukrainian symbolism and folk culture. She was not allowed to exhibit or publish her work. She was a member of the Ukrainian Sixtiers dissident movement, that advocated for freedom of cultural and creative expression.

I swallow hard and even though I am alone, say the words that must be spoken aloud: “We will prevail. This is our land.”

More explosions rock the air and I realize that the Russian invaders must be close now, likely holed up in their tanks and firing directly into houses. They don’t care whether the houses are occupied or not. I’d seen the destruction firsthand when I’d ventured out yesterday. I thought about the possibility of stocking up on food, and since there was no phone service, risked a quick walk outside. Not far around the bend, I saw that a mountain of rubble blocked the roadway where a two-story house stood. Petro, a neighbor who’d come out, warned that soldiers had killed an elderly man riding his bicycle when he’d gone out looking to buy bread. Petro was running low on food too. Even so, my neighbor, who wasn’t far from being elderly himself, talked of an evacuation bus and hoped to flee that very day.

“It’ll be difficult, of course. We might come under fire. Missiles even. We’ll have to drop to the ground as soon as we hear whistles of exploding shells. The only way to get through is to take the roundabout path through the woods to be sure to get to the Ukrainian checkpoint. Then to the bridge if it still stands,” Petro said.

I saw him stare at me as he chewed his lip. I wasn’t sure if he was really expecting me to join him and any other neighbors on this dangerous trek. I knew he was weighing our options. Petro is a stout man with a pronounced limp. His face was haggard. I am 84 and my days of running through fields have long passed. We are both past our prime. But in some integral part of me, I am still the young woman who’d defied my family and gone to study art against their wishes. Who’d chosen to resist the Soviet authorities and created the kind of artwork that called from my heart. Of course, there’d been a price to pay for that as there always is for such things.

Petro knows nothing about this aspect of my life. “It may be too risky,” he finally admitted. Dark steady eyes locked on me. I held his gaze and then he looked away. “I need to check on my daughter-in-law and grandchildren first. Be ready. If there is a chance for any of us, I will come.”

As for me, there is nothing to do now but to stay here in my home and wait for our troops to drive out the invaders. It is hard to believe that our peaceful city, long a place of respite as it is surrounded by a forest of pines, has come under attack. There is no sense to any of this and yet I know how close we are to Kyiv. They mean to take the capital.

I instinctively glance toward the corner of the bedroom, where an icon of the Virgin Mary, holding a baby Jesus in her arms, hangs on the wall. I walk over and study her serene expression, the tenderness in her wide eyes as she clasps the baby close to her. I ask for her protection, a prayer tumbling quickly from my lips. Then I run my fingers over the embroidered linen rushnyk draped around the icon as though I am stroking a cat. This was one of the first ritual cloths I’d embroidered so many years ago. How I’d enjoyed the mix of using yellow, green and red threads against the somber hues of the black. Incorporating ancient lines and patterns that our ancestors created, forging a close magical connection with the world of nature. My mother, who was also an avid embroideress, taught me that each detail was intentional and that the patterns revealed special written symbols. I’d loved them all – circles, crosses, stars, squares and spirals – but from the start, I was especially drawn to triangles, symbols of the narrow gate leading to eternal life.

It is well-known in our country that a house without a rushnyk is not a home. At least that’s what my mother always told me, quoting one of her many Ukrainian proverbs. I take solace that I am left with the icon and rushnyk as the rest of the walls in my home are mostly bare. A few months before the war started, my friend Tetyana from the Sixtiers Dissident Museum in Kyiv, agreed that this seemed like the right time to transfer my artworks to the museum. It was something I’d been planning to do for quite some time as she talked about showcasing my work on a larger scale. And although we didn’t really believe the dictator would invade in full force, deep down we knew we had to be prepared for everything. Our land and culture have been ravaged for centuries. I have faith that our army will repel this latest horde of invaders.

For a moment my shoulders sag. I feel tired as I’d barely slept, halfway expecting Petro to show up at my door during the night. Outside, there are more explosions. They seem to last longer and longer. Then the light sputters out and this time, does not return. I wait for a long while and then notice that even with the windows closed, there is a strange smell. I head to the windows in the living room and carefully peer out from behind the lace curtain. In the distance there is a funnel of smoke. From what I can see, there is nothing burning here in my yard, which is more isolated from the rest of the town, but the smell is unmistakable. Suffocating. My heart races. A cough rises up in my throat, but I keep my eyes on the yard outside. There is no movement. No sign of invaders. For the moment I am safe. I stomp my foot, all semblance of any trepidation transforming into anger. I know what I must do.

For now, there is a lull and silence reigns outside. I sit in my chair and think of my circle of friends in Kyiv. Just last month, weeks before the invasion, a handful of them had gathered here with me to celebrate my birthday. They’d come with champagne and flowers, even a Kyivskiy torte with its rich buttercream filling and light meringue layers. We’d laughed long and hard that day and talked about art and new happenings in Kyiv. An exhibition of my artwork was being planned now that my entire collection was at the museum. The evening had even ended with the singing of Ukrainian folk songs.

But before we bid our farewells that night, Tetyana – who’s quite a bit younger than me – asked if I had any recollections from “those days” that I wanted to share with them. When she talks about “those days,” I know she wants to hear my stories from when I was young and seemingly fearless – when I found my place within the Sixtiers dissident movement. Living in Kyiv by then, I’d been drawn into an expanding circle of artists, musicians and writers who’d resisted Soviet ideology. We didn’t consider ourselves to be heroes. We did what we were compelled to do. What we had to. Honoring our traditions and speaking the language of our ancestors was the right of each one of us.

There was so much I could have said. I could have talked all night. I started by telling them more details about my childhood. How my parents worked hard as we lived on our homestead near the Bucha River. My sister and I loved to run and hide in the nearby forest, spinning in circles and dancing like wood nymphs. Picking wildflowers and then weaving them into wreaths, placing them on our heads like crowns while we hunted for mushrooms. Our grandfather taught us which mushrooms to avoid and which ones to seek out. It became the greatest treasure hunt. We grew up on folk tales and folk songs that he would entertain us with during these outings. Of course, there were many chores to be done around the house and outdoors, but I didn’t even mind milking the cows and would often run to the barn and air my grievances to them after an argument with my sister or parents.

Still, there was never enough money to go around. My mother would sit up late at night, embroidering and sewing, to earn spare change. She taught me all she knew. Yet I’d found my passion as a young child when I held a pencil in my hand and learned to draw. A world of wonder opened, and I fell headlong into it. I took lessons and refined my skills. As I grew older, my parents became worried about my future and wanted me to stop focusing on art.

“What kind of career will you have? You need a solid profession so that you don’t have to scrape by like we do,” my mother said. When I’d persist, she would slap the pencil out of my hands. I didn’t give up. There was nothing they could do to make me stop. Eventually they realized this. But when I entered art school, I was on my own and had to make do with little food and even less money. I was often unwell and even hospitalized. My teachers were kind and offered help, and when I recovered, I vowed to find some way to support myself in this new life.

My friends leaned back in their chairs and listened as I spoke even though I could tell Tetyana wanted me to keep going, afraid I’d grown tired and would soon stop. She needn’t have worried. I’d learned to live with a certain isolation when my Oleksiy died some years back, but that night of my birthday party was different. I was willing to share even the personal details I often kept to myself. Perhaps it was the buildup of Russian troops on the border and the realization that once again, the most basic of our freedoms were being threatened.

I could hardly bear the thought of it. Our country had come so far from those days of my Soviet youth. I took a breath and went on with my story. In the 60s, I wore my dark hair long, pleated in a single braid. I sewed and embroidered my own clothes and wore them to literary readings and rallies. Some people laughed at me, but I didn’t care. I traveled to villages in search of old embroidery pillows and blouses, exchanging new bedding in return for these treasures. I wanted to design clothes with these embroideries. To give new life to what had been restricted. There were enough of us to make a difference and that’s what we did. Some of us painted, some of us wrote poetry, some printed underground pamphlets filled with the poems of those long banned as well as our contemporaries. Many were arrested. Some were killed or sent to Siberian labor prison camps. Many of us weren’t allowed to exhibit our artworks or hold regular jobs in our field. We were being watched. We had to be careful about who we could trust. Our homes were searched. But we just kept on.

I paused then and looked at my friends. “Fight — and you will win,” I said, quoting the words of Taras Shevchenko, our 19th-century national bard, whose portrait I’d painted so many times on placards during those days.

Although I am surrounded by gray walls and darkness, I find that when I close my eyes, I can see all the vivid colors that I loved to splash onto my paintings. It is spring outside, after all, but the Bucha spring I see is not one of rubble and smoldering fires and people running for their lives to outrun missile strikes and invaders. Instead, I see a flowering wreath, a young couple and shimmering folk costumes.

“Bucha has been liberated,” he said, and his eyes are wet with tears. “Hang on. Help is on the way.”

I try to speak but the words don’t come. I can’t even whisper. I can’t move. It is only when our soldiers carry me out the front door, only when I see the blue sky over me, only then can I tilt my head to the sun.