I was only walking down the main drag of my home town this morning – a quaint seaside town in north-west England – surveying the behavior of a largely retired population strolling at leisure. They were window shopping, gazing at clouds from wooden benches covered in memorial plaques, stroking dogs that had become their motive for survival. Waiting for death, I guess, in the most dignified manner. People in their late-sixties, seventies, eighties. You can spot them a mile off. They wear the fatigue of stacked up decades in their stoop, their doddering shuffles, their swollen bellies, receding hairlines, frail shoulders, high-blood-pressured cheeks. In their obsolete clothing. Their palpable surrender to antiquity. Curved spines held up by wooden canes. They know they’re old and they have become it.

Personally, I’m culturally conditioned to expect nothing more or less. Old people are old people, and for some reason I have seventy-six as a benchmark to becoming old. There is no logical explanation for that figure other than a gut feeling shaped by thirty-seven years of worldly observation. Maybe eighty-five before you’re really old. Of course, modern life is pushing that inevitability further back as the decades pass. The question is this: how the hell is the Rock & Roll steam train plowing on in steadfast defiance?

In his 1968 composition, Old Friends, Paul Simon (at the tender age of twenty-six) wrote “can you imagine years from today / sharing a park bench silently / how terribly strange to be seventy.” He’s only just hung his world tour boots up at seventy-eight, but is still fit and making Stateside appearances in that oh-so “terribly strange” decade of septuagenarian fossildom. A twenty-one year old Roger Daltrey famously howled “hope I die before I get old” in The Who’s eponymous youth anthem, My Generation, in 1965. At seventy-five (he’s seventy-six now) he performed at Wembley Stadium with the band’s only other surviving founder member, Pete Townshend (75), and is currently in the US doing further dates. Neil Young, at seventy-four, has become the “old man” that he so beautifully wrote about in his twenties, despite still rocking all over the free world. The Beatles’ tongue-in-cheek “will you still need me / will you still feed me / when I’m sixty-four?” is an expiry date long since passed for Macca (77) and Ringo (79), both still on the road and making records.

You have to ask yourself, are these rockers still relevant all these years later, reaping the financial glories of the reunion-tour warhorse, or have they simply come to terms with the ironies and indignities of becoming old men and women? Some would argue a combination of both (depending on the artist), whilst others would condemn this relic-ridden rock as simple exploitative greed. Bob Dylan (79), for example, has been panned for utterly unrecognizable performances that deliberately detract from his back catalogue. Tickets costing hundreds of pounds are commonplace for these “legends” now; we are left with no choice but to blackmail one-another into attending, regardless of the price. We might never get another chance.

But rock stars aren’t everyday people, are they?

I never had chance to meet my father’s Dad, who was dead in his 50’s long before my 1982 arrival. The only grandfather I did know died at seventy-five when I was in my mid-twenties, in a physical state that can best be described as fragile. He was overweight, had two crocked knees, back trouble, and eventual scarring on the lungs. He couldn’t walk great distances without suffering the terrible effects of arthritic joints, or tight-chested breathlessness. He hid many of his ailments until it was too late, and died five years short of the expected eighty-year average lifespan in the UK. In the summer of 2018, at the same age of my grandfather’s death, I saw Mick Jagger prance and parade about the stage at both London Stadium and Old Trafford football ground, self-assured within the body of a man fifty years his junior. Twenty-eight waist, slim, toned, agile, energetic. He strutted and danced and waved his arms and took off sprinting down the walkways with ease, inspired by the thousands in awe of his presence, his vocal power, his prowess. I watched him perform twice within a week; spent nearly five hours thoroughly engrossed by his showmanship, and consistently staggered by the reality that he, this timeless (if not sourly wrinkled) specimen in front of me acting twenty-two (and doing a bloody good job), was, in fact, seventy-five years old. Seventy-five years old! Seventy-five year olds shouldn’t be…couldn’t be…wouldn’t be doing this, surely? My grandfather – and most grandfathers for that matter – wouldn’t be able to if they wanted to.

The deepening argument is that my grandfather, who grew up in a tough, working-class neighbourhood in Liverpool and worked hard all his life struggling to get by, lived a very different existence to that of privileged, wealthy, super-fortunate Mick Jagger. This is indeed true. Jagger, since quitting the hard life decades ago, has been surrounded by personal trainers, dieticians, top doctors, lifestyle gurus. He has the time and money to indulge in any lifestyle he so chooses – and to his credit, after well-noted 1960’s excesses, he has prioritised his personal health and wellbeing. Even deep into his twilight years (he’s seventy-six now – officially old in my book), he works out five or six days a week, including daily eight mile runs, swimming, boxing, cycling, dance routines and, no doubt a still healthy sex life (he fathered his eighth child at the age of seventy-three with [at the time] twenty-nine year old American ballerina, Melanie Hamrick). He’s a man testing the limits of the human body. He wants to live forever, and he’s having a damn good go.

Jagger’s recent heart scare has barely rocked the boat. He had the valve replacement operation in March 2019, dusted himself off, then got almost immediately back on stage. My grandfather, on the other hand, was spending his septuagenarian days in his chair reading, watching WWII documentaries, eating homemade sausage rolls and Madeira cake, drinking pints of bitter in the local social club, and accepting age with the semi-graceful resignation that most decent people do.

Mick Jagger is an exceptional example of Rock & Roll’s dinosaur elite resisting the curse of age, but he’s by no means the only one. I saw Paul McCartney’s booming hometown show in Liverpool, December 2018, (aged seventy-six), in which he performed a career-spanning three and a half hours of intense, high octane, energetic song. Also slim, sprightly, lucid, age-defying – McCartney looked ready to threaten the unthinkable eighties with the same tour-de-force. Carol King’s Hyde Park show in 2016, aged 74, was an intense, at times thumping, epic celebration of her wonderful Tapestry album. She looked amazing, as she still does at seventy-eight, sang like it was 1971, danced and smiled and moved like a woman half her age.

I saw James Brown do the splits in his seventies. Chuck Berry do the duck walk at eighty-two. BB King had to sit down in the end, but he was eighty-eight when I last saw him perform, and he could still play and sing as though the years had forgotten to leave the starting blocks. I’ve never seen the grandparent generation bounding about town with anything like this kind of exuberance, vigor, dynamism. Supermarkets are like God’s waiting rooms. The coffee houses full of slumped, wilting shoulders. Doctors’ surgeries like traffic light pile-ups on a busy highway; the reflective faces of fatigued, crumpled and submissive aged folk staring at the walls for some kind of unlikely renewal. Jagger and McCartney would squirm at that word – aged. McCartney still does headstands before a show. Maybe the manifestation of ‘youth’ is as mental as it is physical? Most normal people don’t have the music, you see. Could that be it?

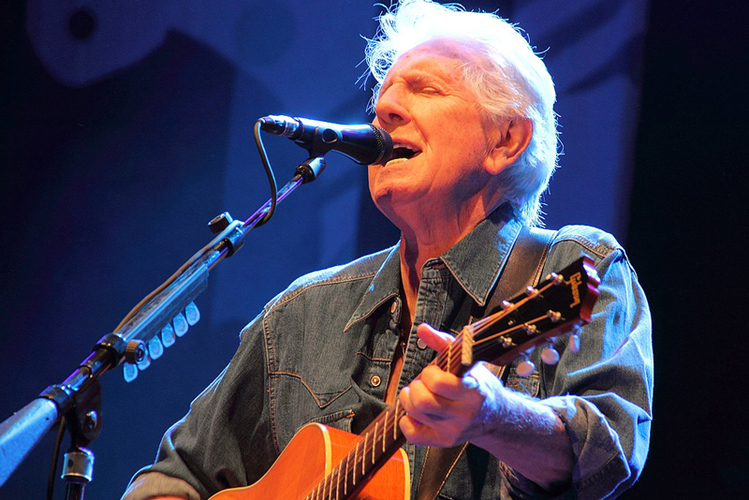

And so the question intensifies further. What is it about this curious, alchemic art-form that keeps people alive, and even more mysteriously, young? Most of my musical heroes still living – people such as Bob Dylan (79), Graham Nash (78), David Crosby (78), Stephen Stills (75), Joan Baez (79), John Mayall (86) – they’re all out there touring. Maybe they live in fear of the reaper, and think if they book another tour he’ll leave them alone at least long enough to finish it?

The list goes on: Eric Clapton (75), Don McClean (74), Brian Wilson (77), Roger Waters (76), Rod Stewart (75), Van Morrison (74), Elton John (73), Tom Jones (80) – they just can’t put their instruments and their microphones down. Many of them are still completely immersed in grueling world tours, long past retirement age for Joe Public. The notion that Ozzy Osbourne is still alive at seventy-one, let alone touring, is preposterous. Cliff Richard, at seventy-nine, had his first number one in 1958 – sixty-two years ago. Jerry Lee Lewis, branded “Rock & Roll’s first great wild man,” is eighty-four and ready to tour. You couldn’t write it.

The surviving founder members of Fleetwood Mac, Queen, Pink Floyd, Aerosmith, Steely Dan, Santana, The Eagles, Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, The Beach Boys, and, of course, The Rolling Stones (long jokingly referred to as ‘The Strolling Bones’) – are all well into their seventies. Maybe they’ve all realised that if they stop the one thing they were put on earth to do, their blood will simply cease pumping that life-force through the veins.

Keith Richards, at seventy-six, is a cartoonish, corpse-like monstrosity with pit-bull jowls, more wrinkles than crepe paper, and bulbous joints born of unnatural excess, and yet still struts around the world’s biggest stages with relative nimbleness, apparently none the worse for his heathenish existence. His drugs were off the street, not the doctor, or so the theory goes. All those who got their drugs off the doctor – Elvis, George Michael, Prince, Tom Petty, Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, Chris Cornell – are gone. ‘Keef’s’ endurance is so incredibly unjust that it can’t help but make the devil within you chuckle.

Tony Bennett, bless his cotton socks, performed at The Royal Albert Hall earlier this summer, and despite his inevitable physical frailties, won great reviews for a commanding performance. He’s ninety-three, with a career that began the year WWII ended (1945), when he was just nineteen years old. That’s a staggering seventy-five years in show business, still active. Petula Clark (87), has recently announced her intentions to revive the part of The Bird Woman in Mary Poppins, a stage play due for London’s West End. She has consistently toured throughout her eighties, and looks a damn site younger for it. Willie Nelson, at eighty-seven, is still on the road with the family band in his green-smoke-encased bus, including his sister, Bobby Nelson, on piano, months away from being ninety. Burt Bacharach (92) is still very much active too, celebrating his seventieth year in the industry. Incredible.

The reality behind the accomplishments of these people is staggering. Music seems to give human beings the inspiration to carry on. Money helps – of course it does. But money can’t buy that kind of spiritual and philosophical need to persist and prolong that music seems to arouse.

One study, recognized by The Economist, suggests that rock stars are “1.7 times as likely to die as others of the same age.” A host of renowned names were gone at the cursed age of twenty-seven; Jimi Hendrix, Brian Jones, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain, Jim Morrison, Amy Winehouse, and Robert Johnson to name a few. A club that sends a shiver down the spine of the Rock & Roll fraternity. With that in mind, it seems even more remarkable that so many peers of these fallen idols are still turning the volume up in stadiums, arenas and theatres all over the world, over fifty years later.

It may be that innate quest to create, or the stimulation that music brings to the brain, or the thrill of human interaction in performing that triggers a will to ignore and evade the aging process – to simply carry on regardless. Every time we lose an aging musician – and I think in recent years of stars like [age at time of death] Leonard Cohen (82), David Bowie (69), Michael Jackson (50), Dr John (77), Glenn Frey (67), Rick Parfitt (68), John Prine (73), Pegi Young (66), Scott Walker (76), George Michael (53), Tom Petty (66), Aretha Franklin (76) – it comes as a shock because they are all still working, still moving their art forward in some capacity. Retirement is synonymous with death. You are not expected to die whilst in a job.

Maybe that is the profound root of the debate here. Maybe that’s why there’s a chance, however unholy or outlandish, that Jagger will still be reaching into his spandex closet into his eighties and beyond, and that the Rock & Roll circus will stutter out with the drip-drop loss of major names rather than blow the fuse in one epic, cataclysmic bang.

God bless Rock & Roll!

Roger Daltrey, by Raph_PH / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)

Paul McCartney / Public domain

Bob Dylan, The White House from Washington, DC / Public domain

Graham Nash, by Schorle / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Joan Baez, by Jtgphoto / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

John Mayall, by Frank Schwichtenberg / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Leonard Cohen, by Takahiro Kyono https://www.flickr.com/photos/75972766@N02/11966502003 / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)