as in burned at

for heresy or misunderstanding—

martyrdom or taken

in error, mistaken

for witch

or saint,

flames a punishment

or cleansing,

depending on where you stand.

Flint or flesh,

kindling or heartwood

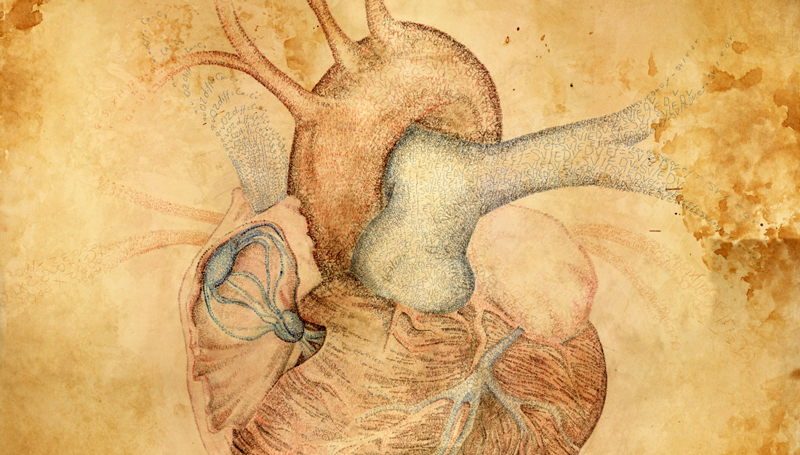

(the heart is the last to burn)—

or to stake, like a tent

in a storm,

rain shield flapping,

but some winds won’t stop

no matter how hard

you pound

in your pegs,

nowhere to gain purchase.

Remember that time

you camped alone in the wilderness

raven screaming from the cliff,

relentless

sun, starving to have a vision?

You could have blown away

easily as a bit of litter,

but something kept you

bound to earth.

What’s at stake—

meaning what have you placed

on your pyre,

what are you willing

to burn

to ash?

Stop interrupting! he said

more than once,

children so full of words

we couldn’t help

it, couldn’t help

ourselves. Near the end

we had to wait

patiently

for him to get the words

out, not barge in

before he was finished.

He loved waterfalls,

did you know that?

Small or large,

famous or not,

trekked up dirt paths

to perch on the edge

and watch water

surrender to gravity’s

pull. He leaned

on rails, bridges, mist

brushing his face,

no words,

we couldn’t have heard

them anyway.

Waterfalls, they say,

pummel the air full

of negative ions, which

(it’s a paradox)

charge positive, an element

that makes you feel better,

more alive. Last time,

in Canada, at Bridal Veil

Falls, he couldn’t make it

to the top, needed

to stay creekside

and watch water

trickle over stones,

the aftermath of so much

power, so much

falling in the distance.

Perhaps we all

(when interred)

devolve to a scatter

of ions,

an interruption,

an error

we meant to correct.

My mother sets a small glass

in front of my father, ferries pills

on a napkin—all colors, all sizes—

reminds him to take them all.

Outside, ivy swarms our small hill.

The walnut tree fattens nuts

within fuzzy husks, and the olives

don’t care what kind of stinking mess

they make on the front walk.

Orange groves have long since disappeared

from this neck of the woods, but they linger

in logos and attitude, scent of blossom

and bark someone, somewhere

might bottle, label: California.

Our juice comes from a tube, I’ve seen it,

frozen, slithering in one wet lump

from the can, my mother precise in the ratio

of water to concentrate, clinking her long spoon

against the pitcher’s insides. It will be years

before I taste fresh-squeezed,

smell the spritz of real juice

released from what binds it.

I eat my Cocoa Krispies,

cereal that grows too soggy too fast,

milk on my chin, while my father

reads the paper, one leg crossed over

the other. Soon he’ll walk out the kitchen

door, fortified by added vitamins,

a baby aspirin, all the things my mother

offers, this conspiracy to keep him alive.

My mother taught me to write

VOID on a bad check—

not a check that was bad in that

it reneged on its promise,

or bad in that it had misbehaved

or gone off,

but bad in that we’d made

a mistake,

written the wrong date

or a wrong number,

wrong decimal point

in the wrong place.

VOID, pressed hard enough

to trace each letter

through to the duplicate—

VOID replicated

so that later, when trying to balance

our books, we’d understand

where the missing had gone.

as in un:

the way a door

will loose from its mooring

in a sudden wind:

all night I heard it:

my old screen moaning

against bare twigs. I knew

I should do something:

get up, joints stiff:

internal fulcra that enable

a body to move. But I couldn’t

move, and the dog barked an alarm:

it sounded, after all, like an intruder:

someone trying to get in.

You don’t notice them until you need

to, the many types of hinges:

Butt or Barrel, Butterfly or Piano:

each quietly doing a job

of coupling. Sometimes

you have to oil them:

get out the WD40 and squeeze:

just so. I want

my father to do it, want him

to show up with his toolbox:

screwdriver, wrench, plier:

every tool you’d ever need, oiled

and ready. He’d hum a little between

his teeth, assess the best approach:

take the whole thing down, or merely adjust:

a little lube here, a tap of the hammer there—

Hinge, as in depend upon,

the smallest things always the most vital:

even the heart, so full of small valves:

they open and close a million times a day.

I wonder if the door between here and gone

swings on a well-used hinge. Think of the piano:

the way the top opens, propped up:

the only way music can fly.