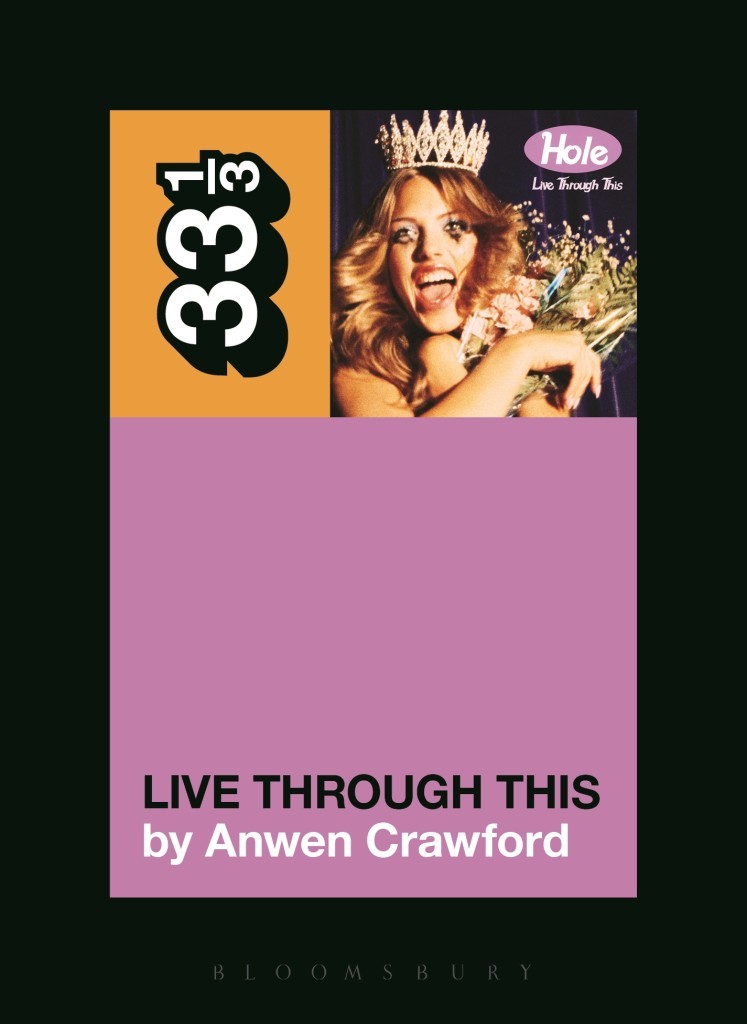

Hole’s second album Live Through This brought punk feminism into the rock mainstream in 1994, and it remains a cultural touchstone for many. In her recently published book of the same title, author Anwen Crawford examines the lasting impact of the album, and of polarizing Hole frontwoman Courtney Love’s unique and confrontational persona. The following is an excerpt from the book’s first chapter, “Violet.” — Victoria Large, FUSION Magazine Editorial Board

‘Violet’ might have been the first Hole song I ever heard, but I can’t remember. That may be because it’s the first song on Live Through This, which I bought not long after its release on April 12, 1994, or it might be the first Hole song I ever heard because I saw the film clip on television, which means that I couldn’t have bought the album until at least early 1995, when ‘Violet’ was released as a single. I think it’s the former, but I couldn’t swear to it.

In a sense, I feel unqualified to be the author of this book. All that recommends me for the post is my undying interest in Live Through This, from which I derive as much pleasure and energy listening to today as I did when it was first released—and not because I now listen through the scrim of nostalgia, but because this album has, in 20 years, never failed to satisfy me as a piece of music.

I was never an obsessive Hole fan. I own no vinyl pressings, no bootlegs, no merchandising rarities. My Hole collection runs to two albums: Pretty on the Inside and Live Through This. I never saw the band play live. During their first Australian tour, in 1995, I was too young to attend (though desperate to do so), and by their second tour, in 1999, I didn’t care. I was so invested in Courtney Love as a punk-rock heroine that Celebrity Skin, at the time, felt like a personal betrayal.

Live Through This is the one Hole album I truly love. I love it for what it taught me, not by doctrine but by inference, about the possibilities of a confrontational, subversive feminism. I am not a person who thrives on conflict, but, in certain situations (namely, street protests and arguments with men), I have called upon the thrilling obnoxiousness of my inner Courtney. She’s the part of me who refuses to be pleasant, and the part of me who loves to win. Courtney was the female artist who loomed largest during my formative years, and, though I can hardly defend all that she has done, I can’t find it in my heart to ever disown her.

‘I love her so much, obsessively so, except when I hate her,’ says Lorelei Vashti, one of several Hole fans whom I interviewed for this book:

Being a Courtney Love fan means constantly mounting a defence for a woman who the world loves to hate. One can be exasperated, alarmed, appalled, proud, but, ultimately, never bored of Courtney Love.

I’m writing here about an album that broke psychic boundaries, not sonic ones—though, really, the two things were tied together. Never discount the power of a woman who rocks. Permission was the word that I heard from fans most often, as if Live Through This, Hole and Courtney Love, in particular, had busted through many an interior chain. ‘I love her to death,’ writes Maranda Elizabeth, who was raised in Ontario, Canada, and began listening to Hole in primary school. ‘Courtney Love gave me permission to be weird, to be mean, to be angry, to be both pretty and ugly at the same time, and to be myself.’

Anwen Crawford is an Australian writer. She is the music critic for The Monthly magazine, and her essays have appeared in publications including Frieze and The New Yorker online.