The man takes the package and holds it in his hands. He opens it.

Inside is a sword.

Very nice of my uncle, the man says.

Yes, says his wife.

She goes back into the kitchen.

A sword, she says. Just what we need.

Honey? he says. Can we hang it on the wall?

What? says his wife. Are you kidding? If that thing falls, it could chop off your head!

The man thinks a moment.

What about in the basement? he says.

Oh, says his wife. That’d be fine.

Honey! he calls– when he’s got the sword up– you really should come down and see this!

I’m sure it looks nice, the man’s wife calls down.

The man reaches out and straightens it.

He’s holding the sword way high up over his head, and using it to point the way forward.

He weighs the blade thoughtfully and holds it out before him. He smiles– it feels good in his hand. He lunges and parries as best as he is able.

Maybe I should take lessons, he says.

The lessons are held in the instructor’s basement. The instructor is very, very strict.

None of you people have any talent at all! the instructor screams at the pupils.

Then he stops and watches the man for a while.

Well, you, he says. You might be somewhat capable.

He is undefeated in combat.

He’s only been practicing a few months, the first says. It’s almost incredible how he blossomed so quickly.

Well maybe he didn’t, the other says.

What? says the first. What do you mean?

There could be another explanation, the second says. What I mean to say is, it is just possible that he’s the reincarnation of a great, great swordsman.

Reincarnation? says the first. You believe in that stuff?

They both turn and look up at the man.

And up there onstage, where he stands holding his trophy, the man overhears their whole exchange.

And that night, when he sleeps, the man again dreams he sees his great-great-great-grandfather before him– still on the battlefield, now screaming a battle-cry.

Now hacking about, stabbing and slashing.

Tell me about my great-great-great-grandfather, he says.

Well, says his uncle, what do you want to know?

Absolutely everything, the man says.

Well, says the man, what happened to him? I mean, you know, in the end?

In the end? says his uncle. He died in the gutter. But he was a great swordsman– that has to count for something!

And so that’s what he does. He gets a better job. He starts going to church; he becomes a little league coach. And his work is rewarded: he is promoted three times, buys a new car, an RV, a bigger house. He takes his family on vacation to Disneyland, and the next year they go to Acapulco. He gets his picture in the paper shaking hands with the mayor. He teaches his whole family to play golf.

Isn’t life grand? the man says to his wife, lying in bed at night.

It certainly is, the man’s wife says.

And everything seems very, very nice.

And now he himself is holding the blade.

Praying that somehow it will end.

In a daze, the man opens up.

There on the porch is a stranger with a sword.

I’m here to challenge you to a duel, the stranger says.

I’m sorry, says the man. I don’t swordfight anymore.

En garde! cries the stranger, and he lunges.

The two fight their way through the rooms of the house, then spill out onto the deck, across the yard. They fight across the grass, around the garden and the swimming pool, swords clashing, flashing in the dark.

The man is a talented swordfighter– very talented– but he’s out of practice, and the stranger is better. It doesn’t take long before the tip of the stranger’s sword is whittling away the man’s skin.

I give! yells the man. I give! I yield!

But the stranger just shakes his head.

You can’t yield, he says. This fight is to the death!

Please, have mercy! the man says.

Mercy? says the stranger. I don’t know what that means.

He knocks the man’s sword to the ground. He raises his own above his head for the killing blow.

But just then a shot rings out.

The man looks over. His wife is on the back porch.

She’s holding a smoking gun in her hand.

His wife steps down from the porch. She moves across the lawn, tucking the gun into her robe.

Don’t be silly, she says. Of course.

He frowns, then hears a noise. He turns and looks toward the fence. And there, on the other side, he sees his next-door neighbor, holding a crossbow in his hand.

Don’t worry, says the neighbor. We wouldn’t have let him get you.

The other neighbors are standing to the side. One has a flamethrower, and the other a pair of nun-chucks. Another has brass knuckles on either hand.

The man stands there, staring.

His wife touches his arm.

It’s all right, she says. It’s all okay.

She smiles and gives the stranger’s body a kick.

Let’s get this in the ground, though, she says, before it starts to stink.

They put away their weapons, and they turn out the lights.

And when they go to bed, the dreams don’t come.

benloory.com

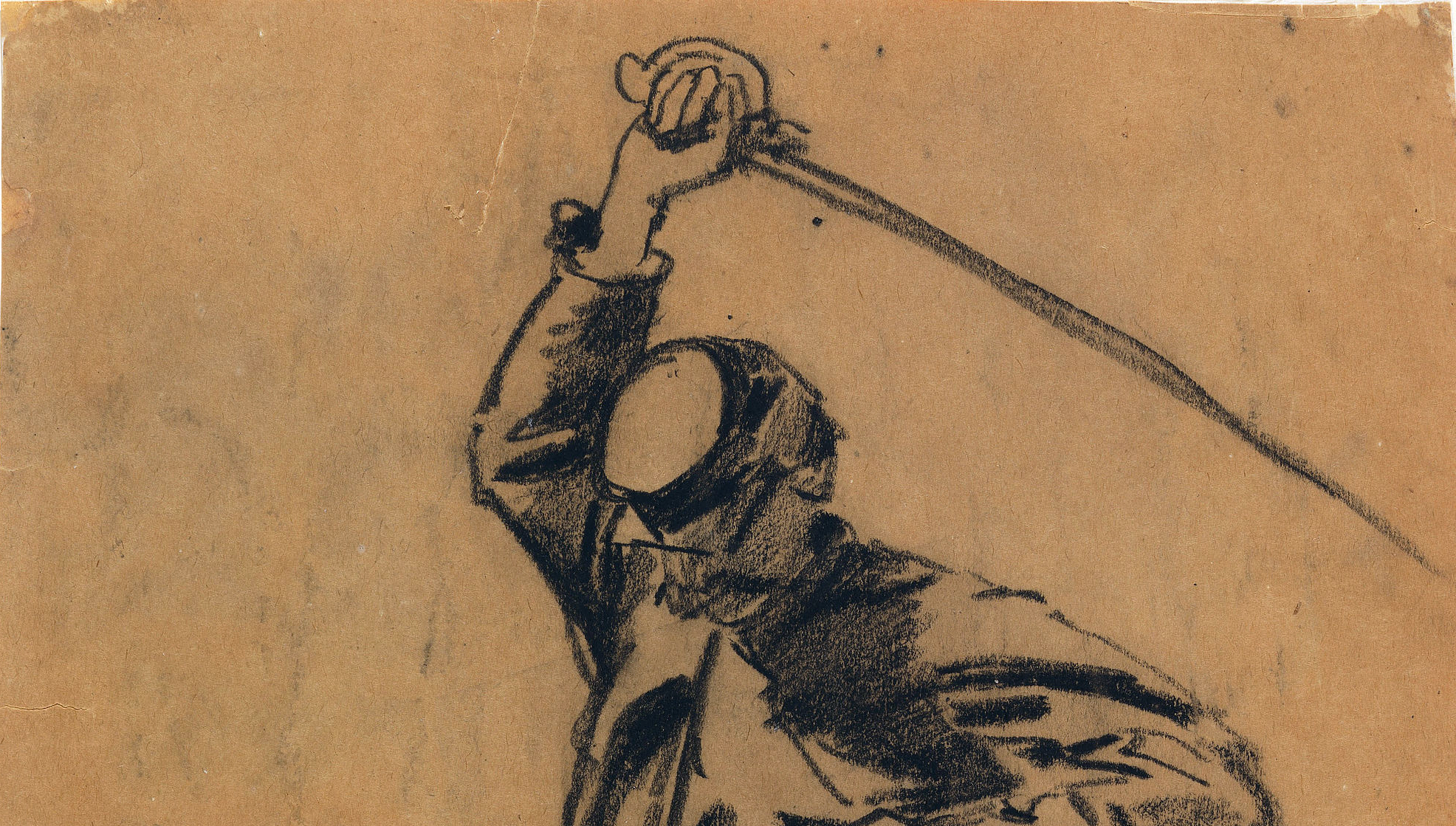

Homer, Winslow. “Cavalry Soldier with Sword on Horseback,” 1863. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons.org.