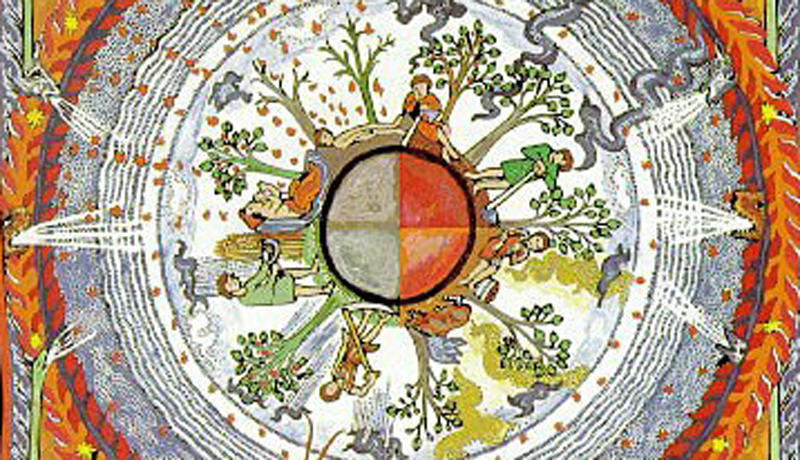

Children that attend public school in the United States tend to start learning about famous composers in elementary school music classes. They learn plenty about Beethoven, Bach, Handel, and Mozart. While such composers are undeniably important to the history of western music, children are not exposed to a single instance of women composers in the classical tradition. Beyond that, woman composers have been so thoroughly erased from history (until quite recently), that even these children’s teachers are not always aware of their existence. For example, Hildegard of Bingen, who wrote a liturgical drama that is arguably the oldest surviving morality play known to the history of western music, was a name unrecognized by longtime, now-retired elementary music instructor, Claudia Tibbetts. Tibbetts lamented not knowing of such an influential woman composer, especially as a female musician herself.

The use of the female sub-genre is being employed in concert programming, and education in some places, in order to expose the public to the works of great women composers. While the effort to get people to listen to and learn about women in music has resonated with some, Amy Beth Kirsten, writer for New Music Box, regrets this, saying: “It pains me to think that we are ‘celebrating’ composers of the female sex by criticizing ensembles (who are supporting a diverse body of excellent works) for not programming enough of them. These ensembles are surely programming music they find compelling. I would hope they are not basing their programming choices on gender, but rather on excellence.”

Kirsten has a point in her assertion that ensembles should build programs around music that compels them. However, she fails to see that one cannot be compelled by something that they have never heard. By asking ensembles to include more pieces by women in their programs, the idea is not that they should simply select a piece that fits the bill and play it. There is as much variety in the works of woman composers as in the works of men. Out of all of the many acclaimed pieces written by accomplished women over the years, there are bound to be at least a few that resonate with a group looking to perform a work composed by a woman.

The biggest obstacle to this occurrence is that it requires the people in charge of programming events to first listen to women’s compositions on a similar scale to those by men. People already know that they love Stravinsky’s Firebird or their favorite Bach chorale, because they have been exposed to them for years, but which of Fanny Mendelssohn’s over 460 pieces might be featured next at the BSO concert? Which of Amy Beach’s symphonic works will be seen in a high school band competition this year? The latter might arguably be there more influential decision of the two.

Integrating the accomplishments of women into the way that music history is taught is a crucial method of creating a musical environment that offers the same credibility to both male and female composers. If the power dynamic can be leveled, the first steps toward closing the wide gender disparity in the field can be taken. In The Guardian, Kerry Andrews writes, “It’s glaringly obvious: if girls are presented with examples of successful female creators in all genres, they might view composition as a viable profession for themselves.” It may take a while longer to integrate the history of woman composers into the high school level, but it is already starting on the college level.

There are now courses at many accredited colleges, such as Oberlin, Berklee College of Music, and Columbia University, specifically designed to introduce students to women composers. It becomes a tricky task, though, as tacking the qualification of ‘woman’ onto the front of a course name does indeed separate the woman composers from their male peers. However, it may be necessary, for now, in order to get the names and accomplishments of these women into the academic circulation.

Celebrated composer Kaija Saahairo appears to share this sentiment, stating, “Nobody wants to be evaluated for things other than their actual skills. But I would like us all to realize (or, to be reminded) that the situations in which we make the evaluations are never objective and that our judgments, however rational they seem to us, can always be colored by our biases.” Ideally, historically significant female and male composers will one day be able to be completely integrated chronologically into music education without the fear of the women falling into the shadows of the men. The construct of a sub-genre, in this case, acts mainly as a temporary means to an all-inclusive end. This instance of a created sub-genre of ‘woman-’, is one that is intended and with a clear purpose in mind. The subconscious separation of woman from man that happens carelessly in other aspects of the music industry, which has no well-intended end in mind, has harmful potential.

The stereotype is that if there is only one girl in the band, she is probably the singer. The high school choirs have too many girls, and the jazz bands have too few. Beyond that, the female singer is expected to be less adept at music theory and composition. Evidence of this lies in the surprise of (mostly) male colleagues whenever the opposite is revealed to be true. A woman carrying cymbals into a gig venue is far more likely to be asked if they are dating the drummer than a man. Instruments, especially ‘masculine’ instruments like drums, bass, and horns are often assumed to be played by men by default, and this can result in three basic reactions to their playing. First, if the woman playing the instrument is good at their instrument, she is overly praised for being a female drummer, bassist, etc. This is actually detrimental to her because people’s evaluation of her skill is based upon the novelty of her sex, rather than her hard work and talent. The second is that, if she is not up to the skill level of those evaluating her, the blame is often placed on the fact that she is not playing a woman’s instrument. Once again, the person actually playing the instrument is removed from the equation. The instrumentalist ceases to be the instrumentalist and instead becomes a representation of her gender, which is not fair. The third, and potentially most harmful, reaction to a female instrumentalist, is that she is immediately compared to other women who play the same instrument. There is this mentality in a patriarchal society that there is very limited room for women to rise through the ranks of men. In other words, women are constant competition to other women. This is a toxic mentality that directly blocks the progress of women in any industry.

By creating the sub-genre of ‘female’ (female bassist, female arranger, etc.), the pool for comparison is shrunk down to women versus other women, and only the top women in that sub-genre can be considered competitive with men. This is why the use of the female qualification must be done so carefully. If used in an educational setting for purposes of visibility, as in the case of the history of western music, highlighting women in the field, as a whole, can be a positive tactic. However, outside of the educational setting, the sub-genre can be destructive. In a hypothetical situation, if there were two woman songwriters at the top of their field, but the general opinion was that one was more successful the other, that direct comparison would be the one that sticks with the apparent lesser of the two female writers. The fact that the second writer was also highly successful, even in comparison to her male colleagues, would be second to that woman-to-woman comparison. Another problem with calling women in music ‘female-such-and-such’ is that it creates the illusion that whatever a woman is creating, though in the same field as men, is inherently different from what men are creating.

Being a female musician does not imply a specific style, contrary to stereotypes. A female instrumentalist’s playing may be dainty, or it may knock her guitar out of tune after one song. The same is true for men, of course. By implying that female musicians play or write with a specific flair, the opposite is falsely implied for men. Music knows no gender boundaries, so there is no need for gender qualifications on musicians. Instrumentalist Claire Daly explains plainly, “My choice to play jazz, live this life, and play this instrument was never motivated by a desire to be a pioneer. I’m a baritone player. I never think about being a ‘female baritone player.” She did not intend to do anything revolutionary by playing an instrument that is largely assumed to be masculine. Instruments are not male or female, and it should not be considered groundbreaking to be able to play one for any reason other than recognition of talent or innovation on said instrument.

There is an area of the music industry that is even more exclusionary toward women than that of instrumental playing or even composition: production. Less than 5% of producers and engineers are women. The general, misguided assumption tends to be that the small number of female engineers is due to an inherent lack of interest. Wesley Smith from PreSonus explains, “Men tend to question how women in audio learned their skills or became interested in the industry, as if it must be a very different experience from their own. This is still one of the biggest differences I find in my experience versus those of my friends in other industries.” Women are not as encouraged to delve into the technical aspects of the music industry as their male colleagues, even starting from a young age. Young girls are encouraged to pursue less cerebral areas of their chosen industries, and music is no exception. It is for this reason that the Women’s Audio Mission was formed. Some have criticized the formation of this movement for creating a separation between female and male audio engineers. However, just like in the case with the history of woman composers, it is a necessary step for now. By creating a place where women in audio are visible and supporting each other, young girls are able to see that audio is not a boy’s club. It is something that is just as open for them.

The sub-genre of ‘women’ is a double-edged sword. It often leads to assumptions that what women do must be different than what men do in the same field. Women are also more easily pitted against each other when the word ‘woman’ is placed in front of their job title because it shrinks the pool of competition by at least half, if not more. However, in fields where women are or have been invisible, like in composition or production, creating the sub-genre only serves as a method of spotlighting potential female role models for young women. The ultimate goal is that one day such measures will not be necessary to show the world that women in such fields exist and excel.

Andrew, Kerry. “Why are there so few female composers.” The Guardian. 2012. Web. 4 April 2016.

Kirsten, Amy Beth. “The Woman Composer is Dead.” New Music Box. 2012. Web. 4 April 2016.

Roullard, Ryan. “Category Archives: Women in Pro Audio.” PreSonus. 2014. Web. 4 April 2016.

Saahario, Kaija. “Sexism in Classical Music.” McGill University. Montreal. 3 November 2013. Speech.

Tesser, Neil. “Play like a girl.” Jazziz. July 2006: 26. PDF

Passionate about positively impacting younger generations through the arts, she enjoys writing specifically for younger students. Last spring, one of Jordan’s choral arrangements was performed by an award-winning choir from Spring-Ford High School, whose singers and director were recently featured at Carnegie Hall.

She has written original scripts for kids’ theater camps, coached students for vocal auditions, and composed custom wedding ceremony music. During her time in Boston, Jordan co-produced and worked on creative teams for several musical productions. She is currently in the process of writing a book and lyrics for an original, full-length musical for high school students.

von Bingen, Hildegard. “Werk Gottes”. 12th century (1163-1173). From Liber Divinorum Operum.