By common consensus, television series have become products that no longer merely entertain, but educate and elevate, often requiring from viewers an intense cognitive workout. In this evolution of the form, literature is frequently cited as a touchstone. Present-day dramas on the small screen, it is commonly claimed, are like “visual novels,” particularly resembling the serialized works of 19th-century novelists like Balzac and Dickens. The comparison can be partly explained as intrinsic to the ongoing process of “artistic legitimation” that has turned this specific type of popular narratives into valid objects of academic study. As such, it can be self-interested and misleading, an attempt to dignify a medium that is regarded as inferior, while in fact it should be evaluated and celebrated on its own ground (Mittel 429). If used as a wide-ranging analytical tool, however, the association of television series with literature, and in particular with the novel, can prove to be productive. The very length of the narrative, the slow construction of the fictional world and development of character, the keen attention to details that gradually acquire importance and “density” in repeated patterns of action (Newcomb 256), are all constitutive features shared by the two forms in their different media.

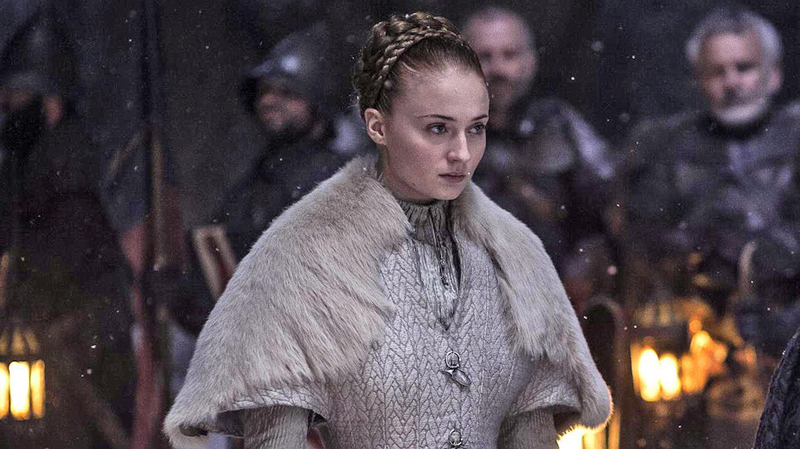

But even before considering the series’ “transmedial” functioning (a very promising field of inquiry), the connection with literature appears to be deep and strong by simply looking at both the background of many writers/producers and the genesis of several shows. As Robert Thompson already put it in his influential study on the “second golden age” of television series, “Quality TV tends to be literary and writer-based” (15). This reflects in the training and cultural tastes of writers and showrunners, who in many cases come from literary studies. Before going to Film School, Matthew Weiner, the creator of the celebrated period drama Mad Men, studied philosophy, history, and literature at Wesleyan University. Jenny Bicks, executive producer for Sex and the City and The Big C, has a degree in English Literature, and Robert Carlock, the showrunner with Tina Fey of the award-winning sitcom 30 Rock, majored in history and literature at Harvard University. When they met at Trinity College, David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, the creators of the acclaimed fantasy drama Game of Thrones, were both advanced students of Irish Literature, and Benioff was even considering an academic career. These are just a few examples (mainly derived from widely available interviews) that help explain why the “literary imagination” is so pervasive in contemporary shows, affecting their narrative structures, character conception, and stylistic techniques. Describing the writing process of Boardwalk Empire, Terence Winter argues that writers “try to make each episode stand alone…It’s like one chapter in a book, I look at it that way” (Kallas 16). Tom Fontana (Homicide, Borgia) “love[s] doing TV series, because [he] like[s] the kind of novelesque nature of TV to take the character on a journey over the course of five years” (Kallas 57), while Phil Abraham, the cinematographer of Mad Men, “actually think[s] of the show as a novel…a lot has to do with observing these characters in moments when they are unobserved” (Goodlad and Varon 370).

Writers and producers do not just invoke the literary analogy to describe how they conceive of their work. Sometimes they are themselves novelists. The list is remarkably long and constantly growing, by now including the names of Richard Price (The Wire, The Night Of, and the upcoming The Deuce), Jonathan Ames (Bored to Death), Tom Perrotta (The Leftovers), Noah Hawley (Bones, Fargo), Leonardo Padura (Four Seasons in Havana), Philip Meyer (The Son), and Gillian Flynn (Sharp Objects, upcoming). The television industry offers novelists so many opportunities, in terms of economic prospects, audience numbers, but also of creative potential, that the traditional novel has come to be seen by some as an endangered genre. According to the poet and critic Adam Kirsch, the likening of TV shows to novels is a covert form of aggression against literature: it suggests that “novels have ceded their role to a younger, more popular, more dynamic art form,” while the latter is in fact much more conventional and “not nearly as formally adventurous as Dickens himself.” To Mohsin Hamid, the “unsayable” fact that novelists (himself included) spend more time watching TV series than reading fiction represents an undeniable crisis for the novel; and yet a crisis can become an opportunity for change, since “the novel needs to keep changing if it is to remain novel” (Kirsch and Hamid).

Many others, instead of a defensive and “apocalyptic” stance (in Umberto Eco’s use of the term), have developed an open, cooperative approach. Jonathan Franzen, who once thundered against the infinite allures of mass culture, mourning the imminent death of the novel, has long recognized that television series respond to the audience’s deep need for the kind of realism offered by 19th-century fiction. An awareness that prompted him to make his most recent novels both complex and accessible character studies in a broad picture of contemporary society and culture (especially Freedom), even persuading him to collaborate on TV adaptations of his own works: the series inspired by The Corrections never saw the light, but another one, adapted from Purity, is soon to be released (Koblin). Although the work of TV writers is more highly regarded than that of their colleagues in the film industry (Kallas 5), for literary authors to collaborate on a show is also an act of humility, compelling them to renounce total control over the creative effort (as well as exclusive credit for it) in order to constantly negotiate ideas and solutions with other peers. Some novelists welcome the challenge of both collective storytelling and of “externalizing” the “organic thought process,” as Noah Hawley puts it, typical of fiction writing: “For a filmed medium, you have behavior and you have dialogue. That’s it. That doesn’t mean that you don’t have to do the organic, internal work, but it is a different process” (VanDerWerff).

The novelists’ involvement in the creation of television dramas helps bring the attention on an often overlooked – because perhaps taken for granted – fact: the literary origins of many contemporary shows. Regardless of the fact that several authors are currently engaged in adaptations of their fiction (in addition to Franzen, Tom Perrotta, Leonardo Padura, Philip Meyer, Gillian Flynn), a remarkable number of series are inspired by books, be they realistic novels, thrillers, epic fantasy fiction, memoirs, historical essays, but also works from other genres or subgenres. To name only a few of the most recent, leading shows, this is the case of Boardwalk Empire, Game of Thrones, House of Cards, Orange is the New Black, Penny Dreadful, The Handmaid’s Tale, as well as the mini-series Olive Kitteridge and Big Little Lies. And yet, since there is no such thing as a literal “transcoding,” these transpositions – as any adaptation process – are an act of interpretation and re-creation that entails both gains and losses.

The impact of the literary discourse on television series does not necessarily imply that they must be drawn from a specific work (of fiction or other kind). This is true of one of most outstanding shows of the last years, Mad Men, which appears to be imbued with a high degree of “literariness” despite the fact that its subject is original. The show is a coral narrative tracing the big transformations that occurred in the US during the 1960s, observed from the microcosm of a Manhattan advertising agency where several characters interact both at the professional and at the private level. Although there are no real protagonists, the privileged character (and point of view) is the agency’s creative director Donald Draper, a fascinating man with a carefully hidden, traumatic past. An immediate comparison with the novel is evoked by a narrative pattern that is especially evident in the first three seasons, the “neo-Lukácsian” parallel between major historical and political events on the one hand, and the characters’ private vicissitudes on the other (Goodlad 329): Don’s shaky marriage with Betty is put in dialogue with the political struggle of JFK and later with his assassination (symbolizing the “death” of the Drapers’ union), a counterpoint reminiscent of the narrative modes of the great realist tradition embodied by Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, George Eliot, and Anthony Trollope. Given his obscure rural origins and his later navigation of the glamorous Manhattan world, Don Draper, in particular, recalls the subgenre of the Bildungsroman. Charles Dickens is a name that comes to mind. Like in a Dickens novel, Don’s trajectory involves an orphan, the flight from a small town and the landing in a big city, the alluring embodiment of success and self-realization but also the site where a complex moral and social identity is painfully achieved (Piga 23). In the last season, however, Don Draper appears to revive a different narrative tradition, that of the classic American novel of initiation which, unlike the Bildungsroman, ultimately rejects the (male) protagonist’s integration into society: as a perfect Western hero, the twice divorced Don, unable to bear his responsibilities as a husband, father, and professional, embarks upon a solitary journey of self-discovery towards California.

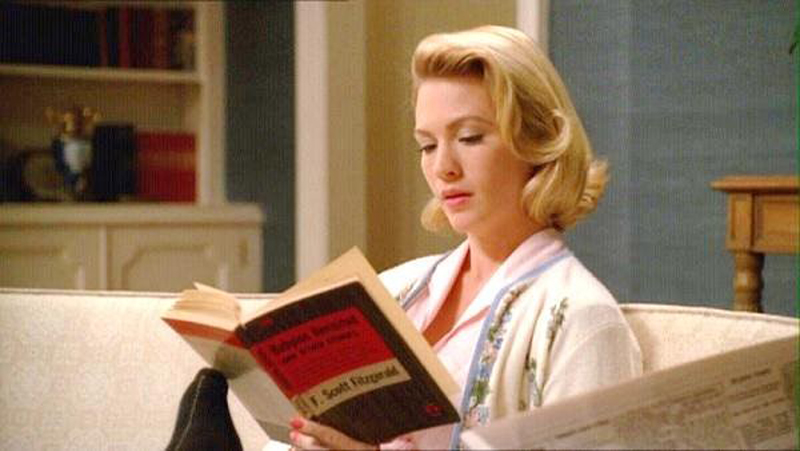

In Mad Men, the dialogue with literature, in particular with the novel, is not limited to the narrative structure and the character construction, but extends both to the use of cultural intertexts and to the style of narration itself. Among the show’s countless references to cinema, music, publicity, and photography, the literary allusions are of paramount importance, often appearing in the form of actual books that the characters are shown in the act of reading. Mary McCarthy’s The Group, Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything, Frank O’Hara’s Meditations in an Emergency, Dante’s Inferno, Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, are only the tip of an iceberg amounting, according to the estimate of one blog, to more than seventy titles. Beside documenting the cultural tastes of that portion of the white, (sub)urban middle class to which the Drapers and their circle belong, the books’ chief function is to elaborate on the characters’ psychology and symbolically reverberate the tangles in which they are caught. When he reads Dante on vacation at the Hawaii, Don is experiencing his moral and psychological descent into hell, while his immersion into the neurotic adventures of the sex-addict Alexander Portnoy alludes to his own promiscuity and clueless life; on the other hand, Betty Draper’s readings (starting from McCarthy’s novel-scandal of 1963) apparently feed her escapism, but in fact strengthen the rebellious side of her personality she tends to repress. Last but not least, the narrative style of the show, famously characterized by an intense, slow-paced attention to material and psychological detail, evokes on one side the notion of effet de réel (Roland Barthes) and on the other that of “serious imitation of daily life” (Erich Auerbach), both a major legacy of the realist novel.

The extraordinary richness and success of current television dramas may be one of the many tokens bespeaking that the hegemony of the book – and more in general of the written word – is over. Their inspiring and multi-layered conversation with literature is at the same time a sign of the fact that the latter’s power has not expired, but rather lives on and is revived in many different forms. Be it an essential equipment of the writers’ background, a source upon which the series are based, or a mise en abyme trace disseminated in the episodes, literature-as-book remains a persistent presence that can hardly be underrated. But if we approach television series as stories containing narrative modes and stylistic techniques typical of specific genres such as novels, or as “virtual novels” themselves, we paradoxically confront a different notion of the literary, one which proves that it has become an unstable concept. Part and parcel of the widespread contemporary phenomenon of re-mediation, by means of which every medium appropriates other media, their techniques and social significance (Bolter-Grusin), TV dramas show that “literature” can circulate through new technologies and supports. They also show that it can be absorbed into the larger category of “storytelling” and “narrativity,” a category that is not so much formal or generic as cognitive and anthropological (Izzo 6). The individual consumption of the book has given way to narratives capable of mobilizing multiple sensorial levels and consumable in a dialogic and collective form (as in the raging phenomenon of fandom); the necessary bond between book and author has been replaced by a practice of authorship that is plural and diffuse. And yet, as readers of old-fashioned written texts and as viewers of high quality television, we still happily inhabit both forms, aware of the possibility that instead of conflicting, they nourish, enrich, and even empower each other.

Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin. Remediation. Understanding New Media. London: The MIT Press, 1999. Print.

Cogman, Camdridge Brian. Inside HBO’s Game of Thrones. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2012. Print.

“Penny Dreadful: The Literary Origins.” Showtime. 27 April 2014.

http://www.sho.com/video/30251/penny-dreadful-the-literary-origins. Web. 2 July 2017.

Goodlad, Lauren M. E. “The Mad Men in the Attic: Seriality and Identity in the Modern Baby¬lon.” Mad Men, Mad World: Sex, Politics, Style & the 1960s. Ed. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky, and Robert A. Rushing. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2013. 320-344. Print.

Goodlad, Lauren M. E., and Jeremy Varon. “A Conversation with Phil Abraham, Director and Cine¬matographer.” Mad Men, Mad World: Sex, Politics, Style & the 1960s. Ed. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky, and Robert A. Rushing. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2013. 361-379. Print.

Kallas, Christina. Inside the Writers’ Room: Conversations with American TV Writers. London: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2014. Print.

Izzo, Donatella, and Vincenzo Bavaro. “Sconfinamenti e abiezioni: Una doppia introduzione.” Ácoma. Rivista Internazionale di studi nord-americani 9 (2015): 5-12. Print.

Kirsch, Adam, and Mohsin Hamid. “Are the New ‘Golden Age’ TV Shows the New Novels?.” The New York Times. February 25 (2014). https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/02/books/review/are-the-new-golden-age-tv-shows-the-new-novels.html. Web. 29 June 2017.

Koblin, John. “Jonathan Franzen’s ‘Purity’ Coming to Showtime, Starring Daniel Craig.” The New York Times. June 1 (2016) https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/02/business/media/jonathan-franzens-purity-coming-to-showtime-starring-daniel-craig.html. Web. 27 June 2017.

Mittell, Jason. “All in the Game: The Wire, Serial Storytelling and Procedural Logic.” Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives. Ed. Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardip-Fruin. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009. Print.

Piga, Emanuela. “Mediamorfosi del grande romanzo realista: dal Bildungsroman al TV Serial.” Between 7.11 (2016). http://www.betweenjournal.it. Web. 20 June 2017.

Sorlin, Sandrine. Language and Manipulation in House of Cards: A Pragma-Stylistic Perspective. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. Print.

Thompson, Robert J. Television’s Second Golden Age: From Hill St. Blues to ER. New York: Continuum, 1997. Print.

VanDerWerff, Todd. “Fargo’s Noah Hawley Tells us How He Juggles 3 TV Shows, Writing a Novel, and an Actual Life.” Vox. August 30, 2016. https://www.vox.com/2016/8/30/12545314/noah-hawley-interview-fargo. Web. 1 July 2017.

Image 1: From Mad Men, Image 2: From Game of Thrones