The Art of Mali Olatunji:

Painterly Photography from Antigua and Barbuda

The Art of Mali Olatunji is the story of an original aesthetic birth, the birth of new creative possibilities in the art of photography. At the same time, this birth brought with it new visions of Olatunji’s native land, Antigua and Barbuda. Ultimately, these new photographic possibilities, and their conversion into definite practices of picture making, emerged as integral parts of a profound transformation in the later years of Olatunji’s life. Until this dramatic transformation, he had been for a long time a fine arts photographer at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who made frequent trips back to Antigua and Barbuda. This transformation was one of those profound inner changes in which we integrate into our conscious life whole new aspects of our psyche that had previously been excluded. Consequently, in these types of integrations we succeed in adding completely new dimensions to our lives. In the case of Olatunji, it was the integrating of a painterly side of himself into his long-standing identity as a fine arts photographer, which was the important fusion behind his transformation. This fusion, like its atomic counterpart, released a lot of original creative energy as it took its course. The photographic work in this text is the direct result of the unfolding of this process of fusion, expansion of identity, and transformation.

The original and distinctive features of the new photographic practices produced by this inner transformation stemmed from the manner in which they motivated Olatunji to use the lines of wood from trees to expand and increase the representational powers of photography. More specifically, the inner fusion motivated Olatunji to use the lines of wood to make photography go beyond the copying of objective or material situations and to take up the symbolic representing of the invisible world of human meaning and subjectivity; in particular, to pursue the symbolic representing of the inner world of the Antiguan and Barbudan colonial and postcolonial subject. Consequently, his woodist extending of the representational powers of photography is inseparable from his accompanying vision of Antigua and Barbuda, his Pan African attempts to empower the black colonized subject, to re-valorize the African spiritual heritage, and to engage with the national projects of Antigua and Barbuda. In this dramatic potentiating of the photographic art, Olatunji – through his woodist practices and techniques – quite unwittingly brought photography into a deep and unprecedented conversation with painting, blurring the boundaries between these two art forms. This was the breakthrough that motivated Paget Henry to write the commentaries on these works, and to describe them as “painterly photography”.

Given the original and “interdisciplinary” nature of Olatunji’s work, his place in the history of Caribbean visual art can only be established by situating him on the border between painting and photography. Located there, we will be able to see more clearly the nature and scope of his contributions Caribbean visual arts. Debates about the nature of Afro-Caribbean painting have consistently linked it to themes of anti-colonialism, Pan Africanism, nationalism and Western modernism. As the following photographs clearly demonstrate, the painterly side of Olatunji’s visual art reflects and expresses all of these themes. The new element that it brings to these discussions are the many aesthetic connections his art establishes between woodism and these themes of anti-colonialism, nationalism, Pan Africanism and modernism. In short, it is a new creative synthesis within both the photographic and painterly traditions of Caribbean visual art.

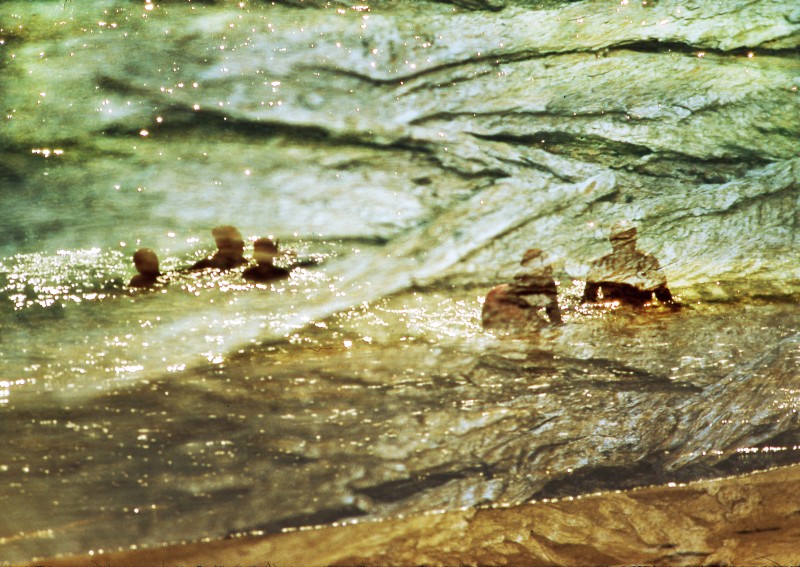

Interpreting these painterly photographs of Olatunji has turned out to be quite a controversial affair. There are those viewers who engage these works primarily through the techniques employed in their production. This particular way of reading and interpreting them we can call the technical response. However a large number of viewers look at these photographs and see primarily faces. One man in particular stands out in this regard. He is Walter Issac. We were at the home of the distinguished Jamaican philosopher, Lewis Gordon. Walter looked at these pictures and said, “I see faces here.” He then turned to Olatunji and asked very directly: “do you believe in ghosts?” He knew nothing of Olatunji’s views about ghosts or what in Antigua and Barbuda we call jumbies. We will refer to this way of interpreting these photographs as the jumbie response. Finally, there are those viewers who look at these works and see first and foremost their painterly quality. Paget Henry was among the first of these.

Initially, Olatunji’s reading of his work moved fluidly between the technical and the jumbie responses with only occasional references to its painterly qualities. Knowing almost nothing about photographic techniques, and being somewhat skeptical about jumbies, Henry’s initial reading was based exclusively on the painterly response. In the course of writing this book, we had lots of extended exchanges regarding these jumbie and painterly responses. Even though these exchanges have brought us closer to each other’s way of reading, our positions are still not identical. Thus Henry’s commentary reflects very much his painterly interpretations, but not to the exclusion of the jumbie readings of Olatunji’s photographs. We have included an epilogue by Olatunji to give the artist of these jumbie photographs the last word.

Even a cursory glance at Olatunji’s attempts to capture Antigua and Barbuda in photographic essays, must call to mind the 1973 volume of photographs and text, Antigua Black: Portrait of an Island People, by Gregson and Margo Davis. Margo’s black and white photographs are simply breathtaking, while the text by Gregson is informative, insightful and poetic. Together, this duo certainly produced an impressive and enduring photographic essay on Antigua. The focus of this photographic essay by Davis and Davis is the fate of “rural Antigua”, which they suggested was caught between the control of a declining sugarcane industry and a still unclear but rising tourist industry. With great poetic and photographic sensitivity, Davis and Davis expressed their concern for the future of the people who populated “rural Antigua” and also for the impact on the ecology of these two industries.

Forty years later, Olatunji’s photographic essay on Antigua and Barbuda, now 32 years an independent nation, must be a very different one. It is also a photographic essay that is rooted in a very different aesthetic. In addition to political independence, the sugar industry is now gone and the budding tourist industry of Davis and Davis’s time has now become the dominant sector of the economy. But in spite social and aesthetic differences, some striking continuities remain. Most obvious are Olatunji’s concerns for the fate of what we can call “service Antigua and Barbuda”, now that the tourist industry has lost a lot of its dynamism, with nothing new on the horizon. Also very striking are Olatunji’s concerns about the impact on the ecology of the tourist trade and also of the now more urbanized lifestyle of St. Johns. The important place of these concerns in Olatunji’s mind is addressed very directly in chapter five.

Chapter one introduces Olatunji and some of the key factors in his life that contributed to this painterly turn in his photography. Following this introduction of our master artist, chapter two illustrates the process of his painterly photographic art, while at the same time it interprets his images of anti-colonialism and post-colonialism in Antigua and Barbuda. In chapter three, we follow Olatunji on his photographic journeys through New York. The woodist/painterly effects in the photographs of this chapter are carriers and representatives of themes of urban alienation and of finding places of solace in the concrete jungle. Chapter four takes us to London and to photographs of impulses of anti-imperialism that have deep roots in colonial Antigua and Barbuda. Chapter five returns us to Antigua and Barbuda to imagine with Olatunji the future of this mini-nation trying to find its way in our increasingly globalized world. Finally, in chapter six we have the last word from our master photographer, Mali Olatunji.

To facilitate the reading of the 111 photographs in this volume, we have organized the vast majority of them into series of three, four or five. These series of images focus on a particular theme in Olatunji’s art. For example, we have from Antigua and Barbuda the Fort James Series and the Big Church Series; from New York the Central Park and the Time Square Series; and from London the Big Ben and Parliament series. This thematic ordering of the photographs will allow us to discuss in more substantive detail the spiritual, aesthetic, social and political themes running through Olatunji’s art.

Mali Olatunji was born on the Caribbean island of Antigua, and spent most of his formative years there as a major league soccer player. His growing interest in photography took him to New York for further training. In 1974, soon after his training, Olatunji was hired to fill one of three positions for fine arts photographers at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. He worked there for twenty-one years, photographing the Museum’s ever growing collection of art works. He also collaborated on a number of book projects, the most important of which was his collaboration with John Elderfield, which produced the important book, The Modern Drawing.

In spite of the wishes of the Museum for him to stay, in 1995 Olatunji resigned his position in response to a strong but very unclear feeling that it was time for him to do something on the arts of his native country. He returned to Antigua and allowed that vague impulse to blossom and flower. The result of that flowering was a new aesthetic, one that he called a woodist jumbie aesthetic. The photographs in his 2015 book, The Art of Mali Olatunji, are expressions of this highly original aesthetic. Further, the woodist texture of this aesthetic gives these photographs their painterly qualities and much of their beauty.