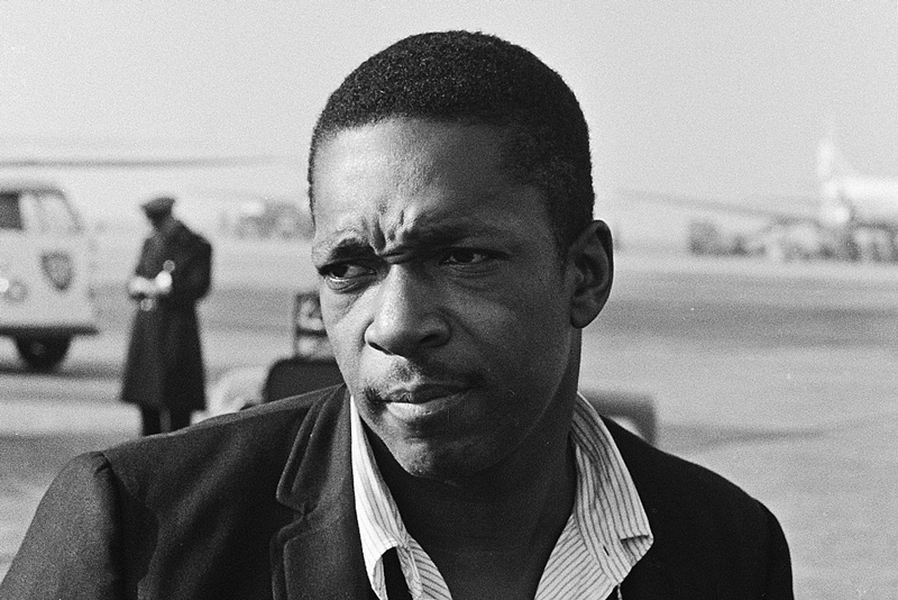

Although Coltrane was undoubtedly one of the defining figures of 1960s jazz, it is surprising that his influence on album sales remains unabated in 2019. As of October 2019, John Coltrane’s new album Blue World, a collection of previously unreleased alternate takes and tracks, is ranked number one on the Billboard jazz albums chart. The album, released by Impulse! on September 27th, peaked at number one during the week of October 12th and has maintained its status for four weeks. The Guardian and Pitchfork selected this album as Jazz Album of the Month and the Best New Issues of September 2019, respectively.

Furthermore, Rubberband, a new album of another jazz giant, Miles Davis, was released by Rhino and Warner on September 6th, 2019 and skyrocketed to number one on the Billboard jazz albums chart by the week of September 28th.

Similar to Coltrane’s Blue World, this album was recorded in 1985 but was not released until decades later. Although Rubberband was unable to maintain its footing on the chart as long as Blue World, the achievement of these two albums by jazz legends has significant implications.

Within jazz history, nearly each decade can be matched with a new genre of jazz beginning within it. For instance, bebop arose in the 1940s, cool jazz and hard bop were prevalent in the 1950s, and avant-garde and free jazz were widespread in the 1960s. Following this pattern, jazz continues to develop today. Alongside young jazz artists emerging every year with their own, unique voices, already-established jazz artists, such as Brad Mehldau, Robert Glasper, and Mark Guiliana, are making a foray into new styles combining jazz with a multitude of other genres including electronic music, hip-hop, rock, and funk, which were previously rarely used in jazz.

In order to continue this innovation and cultivation of new and established musical talent to continue jazz’s evolution forward, these artists need more attention and support. However, John Coltrane and Miles Davis, long-gone artists, take precedence over young jazz musicians in jazz consumers’ minds, making it more difficult for today’s new artists to continue the advancement of their art.

Before imputing the fault to musicians who have continuously thrived over the decades, we have to consider another fact that is crucial in the jazz industry. Unlike other genres of music, the jazz industry is maintained by releasing reissues. This is not to say that this is unique to the jazz industry, however.

The Beatles’ Abbey Road was reissued on September 26th, 2019 to celebrate its 50th anniversary. The album made it into the top 10 on the Billboard 200 chart and achieved huge commercial success—the first time the record had done so since its initial release in 1969 (Caulfield). Where the differentiation lies between the jazz industry’s use of reissues and other genres’ is the jazz industry’s business model’s dependence on them.

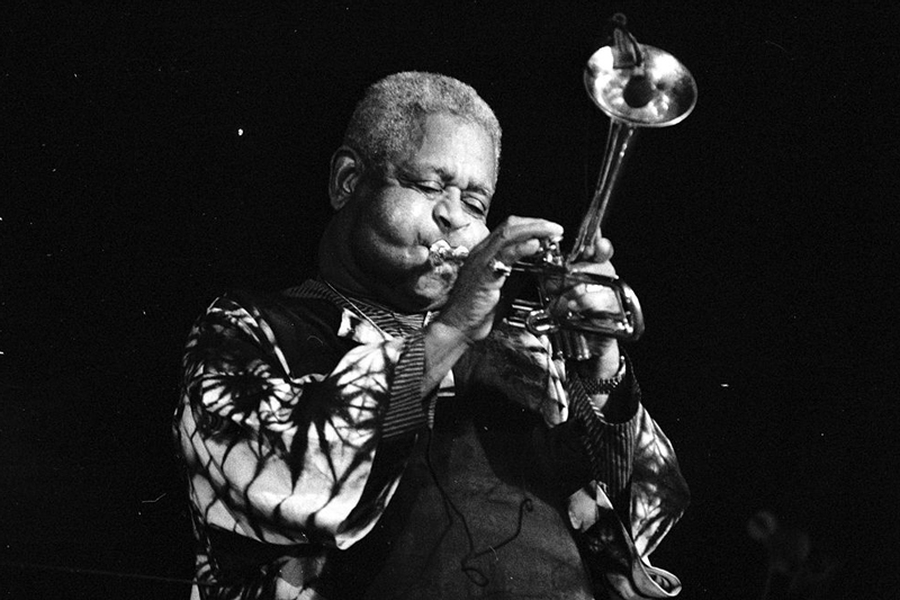

In February 2019, for example, Verve and Impulse! have launched the Vital Vinyl series with UMe. This series is to make 40 reissues of classic albums, throughout 2019, by legendary jazz artists such as Billie Holiday, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Peterson, and others (Sexton). Co-founder of Mosaic Records, record producer and a leading discographer from Blue Note Records, Michael Cuscuna, noted that jazz record labels draw heavily on the sales of reissues as they bring in the highest percentage of profits and without income from them, it is hard to make new recordings. Cuscuna also argues that when jazz beginners go to a record shop, they are challenged with a choice: whether to buy jazz classics that are already proven or buy albums by contemporary jazz musicians. More often than not, this demographic does not want to risk wasting their money buying music from less established and widely known artists (Cuscuna). Though the financial benefit of reissues is undeniable, it is questionable as to whether jazz’s heavy dependence on reissues benefits its musicians and their creative works.

I argue that jazz is hampered by the industry’s heavy financial reliance on reissues because it makes its young artists peripheral. This article is divided into two parts. The first discusses the origin of jazz reissues from the points of view of jazz audiences, musicians, and educational institutions. In doing so, we become able to understand why jazz albums are collected and copied, how jazz music education began, and eventually, how the jazz industry has come into its present form. The second section discusses how the jazz industry is different from the pop industry and the prevalence of jazz’s dependence on classic albums. We may not be able to reach any feasible solution to this problem, but my hope is to bring scholarly attention and awareness to it.

Reissues trace their history back to the 1920s. In the 1920s, while jazz was regarded as “dance music,” jazz collectors began to think of it as “art music” and felt it was necessary to preserve the performance of its early stages and evolution. This being said, early jazz recordings were small in number and jazz record labels could not find any good reason to keep them since they did not have mass appeal (Cummings). Nevertheless, despite the indifference of record labels, jazz collectors believed steadfastly in preservation and kept out-of-print recordings in circulation by copying, selling, and buying them.

As swing became popular music in the 1930s, interest in jazz grew and the public started to demand a short analysis of recordings. Although there had been music criticism in America before the 1930s, the first professional critiques of jazz music were found in European magazines. Notable examples include Revue du Jazz and Jazz-Tango-Dancing of France, founded in 1929, and Der Jazzwereld of Germany, founded in 1930. However, Hugues Panassié, a contributor to Revue de Jazz, got the jump on these European magazines in the 1930s. Panassié established Jazz Hot: La Revue internationale de la musique de jazz. With its high quality and in-depth criticism, Jazz Hot paved the way for, and contributed to early jazz criticism (Welburn).

Meanwhile, the one who spearheaded collecting culture in America was Milt Gabler, the founder of Commodore Music Shop in New York. To make out-of-print recordings, Gabler sought licenses from record labels, and Commodore Music Shop soon became famous among jazz aficionados. A few years later, Commodore Music Shop launched the Hot Record Society (HRS) which issued its own journal, H.R.S Society Rag, and distributed classic recordings to its members (Cummings 109). HRS differed from bootleggers in that they got permission from record companies but their reissuing did not last long as individual recording companies decided to make their own reissues in the 1940s.

A wave of early jazz preservation and jazz appreciation in the 1950s resulted in a copying and collecting boom that was carried out by the successors of HRS. They distributed relics of early recordings through a variety of record labels in order to avoid the eyes of big record companies that owned the original master copies. Although HRS’ successors did not get permission from the record companies, they took advantage of a loophole in the Copyright Act of 1909, which did not grant copyright protection to sound recordings (despite the provision for the mechanical license). Record companies were aware of the exploitation of this loophole, but they did not take any action because the sales of reissues by bootleg firms were negligible. However, bootlegging ran into a brick wall soon after as the companies realized the value of it and started to investigate pirating. In the process of investigation, Victor Records found out their own employees were the ones making bootlegs and even more shockingly, the production of bootlegs was taking place in their own plant under the record label, Jolly Roger. These bootlegs were being funneled through RCA Victor’s custom pressing division. Recordings of Sidney Bechet and Jelly Roll Morton were produced by Jolly Roger, and Victor disgrace itself since it had previously strongly voiced the need for vigilance regarding bootlegs.

Dante Bollettino was a founder of Paradox Industries which was a parent company of Jolly Roger. Before he founded Jolly Roger, Bollettino made reissues of lesser-known musicians such as Cripple Clarence Lofton through Pax Records. However, his work became bolder with his next record label Jolly Roger. Among others, high-profile artists such as Frank Sinatra, Louis Armstrong, and Bessie Smith were included in Jolly Roger’s catalog which was enough to elicit attention (Cummings). When Columbia Records released reissues of Louis Armstrong, the company was confronted with the same albums that were produced by Jolly Roger and already being sold. Armstrong and Columbia filed a lawsuit against Paradox, and Bollettino had no choice but to withdraw. After the lawsuit, he denounced the record companies for just seeking profits and not making records continue to be available to the public. However, thanks to Bollettino, this event resulted in companies realizing the value of preservation of early recordings and caused them to put recordings back in circulation.

If the collecting, copying, and reissuing of records were a form of jazz appreciation by audiences, the form of musician’s jazz appreciation was different from that of audiences. In its early history, jazz was popular music and dance music. Swing played a key role making jazz popular in the 1930s, and since people danced to it, jazz was regarded as “functional” music. The places one found to listen to jazz were ballrooms and clubs, not concert halls. In discussions of music, dichotomies always exist between “high” and “low” and between “cultivated” and “vernacular.” In such discussions, jazz fell into the “low” and “vernacular” until bebop, when jazz experienced a gradual shift toward art music (DeVeaux 6).

Bebop was different from swing in many ways. It was no longer dance music, but music that demanded careful listening. Due to its complexity, chromatic harmonies, and extremely fast tempos, bebop failed as popular music. Nonetheless, it brought an unexpected change to the presentation of the music. Jazz musicians had long been wanting to change the notion of jazz as entertainment, and desired the gentle demeanor of concert hall audiences. However, it seemed like where people listened to music defined how people listened to music (Klotz 25). Nightclubs were unlikely places for careful listening to happen. In an effort to bring jazz outside of the club, Norman Granz, the founder of Verve Records, launched Jazz at the Philharmonic (hereafter referred to as JATP) in 1944, which was the longest-running series of jazz concerts by an all-star cast (Hershorn). Virtuosity and dexterity, characteristic of bebop, were highlighted in JATP concerts, and Granz brought the competitiveness of jam sessions to performances so that his musicians would instrumentally battle with each other (Deveaux 6).

Modern Jazz Quartet (hereafter referred to as MJQ) was another central figure to the transformation of jazz over time. John Lewis, a pianist and artist director of MJQ, applied European classical music vocabularies in his compositions and challenged his audiences with its complex structure. He used fugue form and complex counterpoint when writing music, and believed that in order to understand the music, structural listening was needed. Moreover, all four members of MJQ wore tuxedos for their performances in an effort to link jazz to concert halls. Making complex music and wearing formal attire was to change the mode and location of listening jazz, and ultimately, inspired a heightened appreciation of jazz (Klotz 25).

While jazz, as a genre, received recognition as early as the 1930s as swing gained popularity, it took longer for jazz education to gain respectability and be incorporated into official college curriculums. Jazz first appeared on college campuses in the 1930s. Student-run jazz organizations had jazz ensembles, but the word “jazz” was concealed by another term “dance band” due to its low social status. Dance bands continued in the 1940s but it was not on credit basis. It was after World War II that jazz gained ground, inch by inch, in the field of music education (Luty 38).

The influence World War II had on jazz was not inconsiderable. Professional musicians were enlisted in the army during the war and they performed in military and jazz bands. After the war, thanks to G. I. Bill, veterans were able to receive education. Since a lot of servicemen had performed in their military units, they were accustomed to jazz, and this fact prompted colleges and universities to offer jazz courses. Furthermore, the U.S. Navy Music Training School in Washington, D.C. offered their soldiers classes such as arranging, improvisation, jazz harmony, and Naval Academy selected eminent musicians and arrangers as music teachers during wartime and educated their people (Luty 39).

The first four-year institution to offer jazz studies for credit was the University of North Texas (formerly North Texas State College) in 1947. By the end of the 1940s, 15 schools were offering jazz courses and five of them were on credit basis, and another 30 colleges and universities began offering jazz courses in the 1950s. As jazz courses were gradually securing their position in institutions of higher education, collegiate festivals began to take place. The Brownwood Festival was held in 1949, and Downbeat-sponsored Notre Dame festival was held in 1950. There were about 5,000 high school stage bands by the late 50’s and this number doubled about to 10,000 by the late 60’s (Luty 53).

This rapid growth of stage bands brought changes in many different fields. Music publishing companies started to publish books written for stage bands, and musical instrument manufacturers sponsored festivals, granted scholarships, and had professional musicians offer clinics. Moreover, universities and other Teacher Training Schools added stage band to their curriculum, since high-school and college administrators wanted their stage band directors to be formally certified. In 1968, the National Association of Jazz Educators (NAJE) was established and they published a periodical for jazz educators and students named Jazz Educators Journal (Gerritse 157).

Jazz education showed continued growth in the 1970’s and 80’s; Around 400 colleges and universities offered at least one jazz ensemble for credit in the early 1970’s, and over one hundred institutions offered a master’s degree in jazz, and three institutions offered a doctoral degree at the end of the 1980s (Luty 49). In 2019, According to Downbeat Magazine October 2019 issue Student Music Guide: Where To Study Jazz 2020, there are around five hundred schools offering jazz studies in the US, and over 170 schools outside the US.

The growth of jazz programs in colleges and universities spurred the emergence of other jazz-related institutions. Among others, Jazz at Lincoln Center and Smithsonian Jazz reinforced the idea that jazz has a canon. Jazz at Lincoln Center (hereafter referred to JLC), part of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, debuted in 1987, and received its own dedicated performing space in 2004. Since its establishment, JLC has been one of the most resilient and successful jazz repertory orchestras and has played a leading role in elevating the societal status of jazz. This institution is not only for jazz performances, but also offers jazz education to people of different age groups including middle school and high school students, undergraduate and graduate students, and teachers. In addition, since 1995, they have held Essentially Ellington High School Jazz Band Competition and Festival (hereafter referred to EE) annually. EE is a competition to select the top three high school bands in the country and give them the opportunity to present a concert at the end of the festival. As the name suggests, this competition is unique in the sense that high school band directors are given transcriptions of exclusively Ellington’s composition. In 2008, JLC announced that they would be adding an important jazz composer to their lineup every year but it was noted that its center would continue to be Ellington.

JLC’s penchant for historical jazz figures can be explained by its managing and Artistic Director, Wynton Marsalis. Marsalis, a prominent trumpeter who grew up in a family of musicians, has been the center of controversy due to a remark that jazz is a metaphor for democracy and disposition towards traditionalism and conservatism (Sanchirico 289). He has publicly denounced hip-hop, and did not hesitate to show his antipathy towards jazz musicians playing funk, even when it comes to his own brother (Hajdu). His fondness of classic jazz albums has become clear through Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra’s repertory as they generally play the songs of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, and Charlie Parker. In doing so, they not only protect the music’s heritage, but also help solidify the jazz canon. Since JLC wields considerable clout, as they offer a variety of programs to people of various ages, the impact their canonization will bring to the public is not a trifling one.

While Jazz at Lincoln Center has Wynton Marsalis, the Smithsonian Institution has Martin Williams. A prolific jazz critic and historian, Williams has made significant contributions to jazz over the course of his life. He wrote for The Saturday Review, The Evergreen Review, The New York Times, and Downbeat (Morgan). Williams’ best-known book, The Jazz Tradition was published in 1970 where he covers various artists from King Oliver through Ornette Coleman. He included music analysis as well as analyses of the connected nature of music and social phenomena which provides readers a broader perspective on the context from which the music sprung (Watrous).

He was appointed director of the jazz and American culture programs in the division of performing arts of the Smithsonian Institution in 1971, and he released The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz in 1973, which consisted of six-LPs. The list of artists appears in this collection overlaps with the artists in The Jazz Tradition. When The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz was released, it was adopted within college jazz courses throughout America, and functioned as a compass for newcomers to jazz. This anthology was the first to become a part of jazz curriculum and served as a backbone of jazz education for several decades. It became the best-seller and went double platinum. Although, in conversation with Michael Jarret, Williams once said that his writings had no effect on situating artists in terms of who is superior and inferior (Gabbard, 2003), Krin Gabbard notes that

Piracy, bootlegging, and reissues are not confined to the jazz industry. Usually, recordings are reissued to adjust for a change in audio formats (e.g., vinyl albums being reissued on CDs) or to commemorate an anniversary of the artist. Thus, they are common and could be found in other music industries as well. However, the aspect of reissues in the pop industry, in its initial stage, was somewhat different from that of the jazz industry. The bootleg boom arrived in the popular music industry in the 1960s. Unlike their predecessors, jazz bootleggers like Dante Bollettino, new bootleggers in the pop music industry were interested in disseminating music of the moment rather than the past (Cummings). While jazz bootleggers’ objective was to reproduce classic recordings that were small in number or out-of-print, pop bootleggers aimed to make new recordings by illegally recording at concerts or by compiling previously unreleased songs. These recordings became popular among fans; so much so that they were eager to get the unreleased songs while leaving a new album to be neglected. For example, enterprising musicians such as Bob Dylan eventually released bootlegged materials through legitimate record labels. His so-called “Basement Tapes” were originally released by Trademark of Quality in 1969, and in 1975, Dylan’s own label (Columbia) issued a deluxe version of that material. Not long after, several of bootleg firms were established and made albums with minimal information on the cover in an attempt to fly under the radar of major record companies. However, some firms were bold. Rubber Dubber, an ill-fated bootleg label that made albums of Jimi Hendrix and James Taylor, even sent reviews to Rolling Stone proudly revealing its name (Cummings 247).

Musicians in the pop industry, the likes of the Beatles and Bob Dylan, have gained greater popularity than jazz musicians and therefore the demand for and the profit of albums were higher than that of the jazz industry (Cummings 253). One of the most influential bands in popular music history, the Beatles, have released numerous reissues. In fact, they have released three reissues during the past three years: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 2017, self-titled album The Beatles (also known as the White Album) in 2018, and Abbey Road in 2019. All of these albums were reissued to commemorate the band’s 50th anniversary, and all three albums yielded commercial success. Another legendary band, Led Zeppelin, had a reissues campaign as well. In 2014, they made reissues of their first three albums, Led Zeppelin, Led Zeppelin II, and Led Zeppelin III with unreleased songs. In 2015, they made reissues of their final three albums, Presence, In Through the Out Door, and Coda (Grow).

Although the concept of reissues is prevalent among a variety of music industries, the repercussion it has on the jazz industry is greater than other sectors of music. On the Billboard Jazz Digital Song Sales chart, only one song, Morning Walk by Brian Culbertson, is a new release among top fifteen songs on the week of October 19th. Of the top fifteen songs in the chart, ten have maintained their position on the chart for more than three hundred and thirty weeks. Even more notable is that the number one song on the chart, What A Wonderful World, by Louis Armstrong, has been Number One for two hundred and seventy-five weeks and succeeded on the chart for five hundred and ten weeks. In addition, the top three artists, Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra, and Natalie Cole, all died more than fifteen years ago.

On the other hand, on the Billboard Pop Digital Song Sales chart, none of the top fifteen songs were on the chart more than twenty-eight weeks on the week of October 19th. All the songs on the chart, except for two songs, were released in 2019 and none of the artists are dead. Although other music industries make reissues every now and then, they do not depend on reissues as much as the jazz industry. According to one article from The Atlantic, many jazz record labels are losing their interest in cultivating new artists. David Hajdu notes:

A collaboration with National Museum of African American History and Culture, The Smithsonian announced that in the spring of 2020, they will release Smithsonian Anthology of Hip Hop and Rap which will include nine CDs, more than one hundred and twenty tracks, and a three hundred page book with extensive essays, notes, and never-before seen photographs. This anthology covers hip-hop’s evolution from its beginning to the present, and they have developed this project in an effort to “explore important issues and themes in hip-hop history” and “provide a unique window into the many ways hip-hop has created new traditions and furthered musical and cultural traditions of the African diaspora (Leight).” As jazz was canonized and reinforced its stature in colleges and universities after The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, keeping track of Smithsonian Anthology of Hip Hop and Rap and seeing whether it ends up repeating this pattern will enable us to have better understanding of the problem, lead us to further research, and possibly bring us viable solutions.

“Best New Reissues.” Pitchfork, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/best/reissues/.

Caulfield, Keith. “The Beatles’ ‘Abbey Road’ Returns to Top 3 on Billboard 200 Chart After Nearly 50 Years.” Billboard, 6 Oct. 2019, https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/chart-beat/8532282/the-beatles-abbey-road-returns-billboard-200-chart-top-3.

Clark, Philip. “Wynton Marsalis: Trumpeting Controversial Ideas of Classicism.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 6 Nov. 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2015/nov/06/wynton-marsalis-trumpet-controversy-miles-davis-dave-brubeck.

Cummings, Alex Sayf. Democracy of Sound: Music Piracy and the Remaking of American Copyright in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Cuscuna, Michael. “Strictly on the Record: the art of jazz and the recording industry” Jazz Research Journal [Online], 21 Mar 2005

Deveaux, Scott. “The Emergence of the Jazz Concert, 1935-1945.” American Music, vol. 7, no. 1, 1989, p. 6., doi:10.2307/3052047.

“Digital Edition: October 2019.” DownBeat, http://www.downbeat.com/digitaledition/2019/DB1910/default.html.

Fordham, John. “John Coltrane: Blue World Review | John Fordham’s Jazz Album of the Month.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 27 Sept. 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/sep/27/john-coltrane-blue-world-review.

Franckling, Ken, and United Press International. “JAZZ REISSUES BOON TO SOME, BANE TO OTHERS.” Chicagotribune.com, 4 Sept. 2018, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1985-07-18-8502170014-story.html.

Gabbard, Krin. “Canon (jazz).” Grove Music Online. 2003. Oxford University Press. Date of access 23 Nov. 2019,

Gerritse, Jaap. “Jazz and Light Music in Music Teaching Institutions.” Fontes Artis Musicae, vol. 32, no. 3, 1985, pp. 157–160. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23505792.

Grow, Kory. “Led Zeppelin Announce Final Three Deluxe Reissues.” Rolling Stone, 25 June 2018, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/led-zeppelin-announce-final-three-deluxe-reissues-60466/.

Grow, Kory. “Led Zeppelin to Reissue First 3 LPs With Unreleased Songs.” Rolling Stone, 13 Mar. 2014, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/led-zeppelin-to-reissue-first-3-lps-with-unreleased-songs-199934/.

Hajdu, David. “Wynton’s Blues.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 1 Mar. 2003, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2003/03/wyntons-blues/302684/.

Hershorn, Tad. Norman Granz: the Man Who Used Jazz for Justice. University of California Press, 2011.

“Jazz Digital Song Sales: Page 1.” Billboard, https://www.billboard.com/charts/jazz-digital-song-sales/2019-10-19. Please note that Billboard does not allow non-subscribers to see the charts.

“Jazz Music: Top Jazz Albums & Songs Chart.” Billboard, https://www.billboard.com/charts/jazz-albums/2019-11-02.

“Jazz Music: Top Jazz Albums & Songs Chart.” Billboard, https://www.billboard.com/charts/jazz-albums/2019-09-28.

“’Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology’ Highlights Genre’s History.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 26 Mar. 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/jazz-the-smithsonian-anthology-highlights-genres-history/2011/03/17/AFxxfubB_story.html.

Klotz, Kelsey A. K. “On Musical Value: John Lewis, Structural Listening, and the Politics of Respectability.” Jazz Perspectives, vol. 11, no. 1, Feb. 2018, pp. 25–51., doi:10.1080/17494060.2018.1528996.

Leight, Elias. “Smithsonian Details, Seeks Funding for Massive Hip-Hop Box Set.” Rolling Stone, 25 June 2018, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/smithsonian-details-seeks-funding-for-massive-hip-hop-box-set-118908/.

Luty, Bryce. “Part I: Jazz Educations Struggle for Acceptance.” Music Educators Journal, vol. 69, no. 3, 1982, pp. 38–53., doi:10.2307/3396019.

Luty, Bryce. “Part II: Jazz Ensembles Era of Accelerated Growth.” Music Educators Journal, vol. 69, no. 4, 1982, pp. 49–64., doi:10.2307/3396145.

Morgan, Paula, and Barry Kernfeld. “Williams, Martin (jazz).” Grove Music Online. 2003. Oxford University Press. Date of access 23 Nov. 2019,

“Pop Digital Song Sales: Page 1.” Billboard, https://www.billboard.com/charts/pop-digital-song-sales/2019-10-19.

Sanchirico, Andrew. “The Culturally Conservative View of Jazz in America: A Historical and Critical Analysis.” Jazz Perspectives, vol. 9, no. 3, Feb. 2015, pp. 289–311., doi:10.1080/17494060.2016.1257732.

Sexton, Paul. “Verve and Impulse! Launch Vital Vinyl Jazz Reissue Series: UDiscover.” UDiscover Music, 25 Feb. 2019, https://www.udiscovermusic.com/news/verve-and-impulse-launch-vital-vinyl-jazz-reissue-series/.

“SHOW BUSINESS: Striking the Jolly Roger.” Time, Time Inc., 11 Feb. 1952, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,815986,00.html.

“Smithsonian Anthology of Hip-Hop and Rap.” Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, https://folkways.si.edu/smithsonian-anthology-of-hip-hop-and-rap.

Watrous, Peter. “Martin Williams, A Jazz Critic, 67; Wrote on Culture.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 14 Apr. 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/04/14/arts/martin-williams-a-jazz-critic-67-wrote-on-culture.html.

Welburn, Ron. Jazz Magazines of the 1930s: An Overview of Their Provocative Journalism.