–Renee Descartes 1596-1650

Wittgenstein held that the meanings of words reside in their ordinary uses, which is why philosophers trip over words taken in abstraction. Philosophy had gotten into trouble by trying to understand words outside of the context of their use in ordinary language.

For example: What is reality? Philosophers have treated reality as a noun denoting something that has certain properties. For thousands of years, they had debated those properties. Ordinary language philosophy instead looks at how we use the word reality in everyday language. In some instances, people will say, “It may seem that X is the case, but in reality, Y is the case”. This expression is not used to mean that there is some special dimension of being where Y is true, although X is true in our dimension. What it really means is, “X seemed right, but appearances were misleading in some way. Now I’m about to tell you the truth: Y”. That is, the meaning of “in reality” is more akin to “however”. And the phrase, “The reality of the matter is …” serves a similar function — to set the listener’s expectations. Further, when we talk about a “real gun”, we aren’t making a metaphysical statement about the nature of reality; we are merely opposing this gun to a toy gun, pretend gun, imaginary gun, etc.

Wittgenstein’s method requires a careful attention to language in its normal use, thus “dissolving” philosophical problems, rather than attempting to solve them.

Those would be ordinary reasons to use the language of real and unreal or fake – how we’ve learned to use these words. In our ordinary language real and unreal are used to contrast one event or experience with another. When you take them out of that context to a place where there is no contrast – in “everything we experience is an illusion,” for example, there is no possible contrast to unreal – the use of the word evaporates and you are left wondering what the unseen, real world could be made of. We still feel the drive of the word to evoke a contrast, but we’ve taken it out of a context where one is available. The language has gone on a holiday.

Of course, it took me years of study (3 years as a U of M undergraduate, 4 years of graduate study and Indiana University, including a Master’s in Literary Criticism from the Kenyon School of Letters) to follow the trail and find, a la Wittgenstein, the source of the mystery.

But the journey, in Eliot’s words,

I spent six years teaching Philosophy, both at Indiana University as a Teaching Associate and The University of Notre Dame as faculty, during which time my interest began to shift to music, then to the crack between music and poetry – songwriting. I’ve been teaching lyric writing and poetry for the last 4 decades at Berklee College of Music, during which time the mantra “How is that word used in Ordinary Language?” has leaked into my teaching of songwriting and poetry, morphing into the shiny new, but fundamentally related, mantra: “Preserve the natural shape of the language.”

“Is that tree real?” loses its meaning when real is wrenched out of its natural habitat in Ordinary Language. The same thing happens when we allow either musical rhythms or poetic rhythms to overpower the natural shape of words and phrases. We lose meaning. We lose emotion.

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

The Ordinary Languages of Words and Music

Words and notes start with something in common: both belong to dynamic communities of stressed and unstressed members. The trick is to match each with their own type, stressed notes with stressed syllables, unstressed with unstressed. Recognizing which is which is sometimes easy, sometimes an art: depending partly on the words and notes themselves, partly on their context.

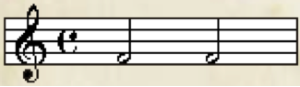

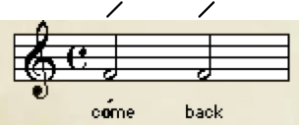

Look at a bar of 4/4 time. The first half-note is stronger than the second, though they are both stressed.

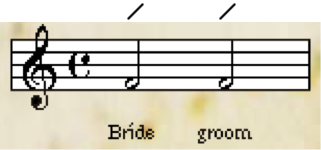

“Bridegroom” would fit the bar perfectly: both syllables are stressed but the first syllable is stronger:

“Bridegroom” would fit the bar perfectly: both syllables are stressed but the first syllable is stronger:

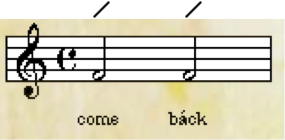

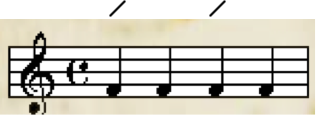

A perfect match. Now look at the phrase “Please darling, come back.” “Come back” is the opposite of “bridegroom.” Again, both syllables are stressed, but now the second is stronger.

Not that a poor match breaks any mythical rules; it just sounds unnatural. We lose the illusion of a real person making a real statement, deflating the emotion of the language and distracting the listener. This is crucial: a song is simply natural speech, exaggerated.

If you said, “Most defeated lovers, sooner or later, dream of making a comeback,” then “comeback” would be stressed like “bridegroom.”

A perfect match.

Words with two or more syllables have an accent mark over one of the syllables, indicates the word’s main STRESS. In English, all words of two or more syllables have a primary stress, creating sonic shape (or a “little melody”) to help your ear recognize the group as a unit. Stressed syllables are

b) louder

c) longer

So how about one-syllable words, the staple of English and especially of lyrics? Don’t bother looking in the dictionary; it doesn’t mark one-syllable words.

One-syllable words are stressed when they have an important job to do, like delivering a message. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs all get sweaty because they work hard, like these:

Like these:

articles (e.g., a, an, the),

conjunctions (e.g., and, or, but),

auxiliary verbs indicating tense (e.g., have run, had run),

auxiliary verbs indicating mood (e.g., might run, may run),

personal pronouns (e.g., I, him, their),

relative pronouns (e.g., which, who, when)

I asked you to throw the ball to me, not at me.

I asked you to throw the ball to me, not to her.

I asked you to throw the ball, not him.

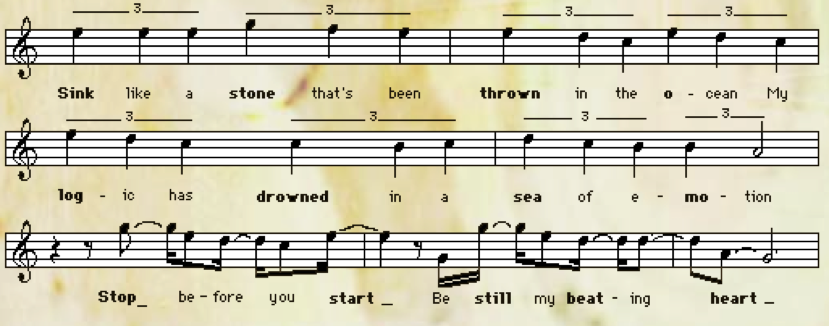

Look at this verse is from Sting. Read it a few times first, then try to mark its accented syllables.

My logic has drowned in a sea of emotion

Stop before you start

Be still my beating heart

My logic has drowned in a sea of emotion

Stop before you start

Be still my beating heart

My logic has drowned in a sea of emotion

Stop before you start

Be still my beating heart

All the other unstressed words are standing around directing traffic. The rhythms are pretty regular, moving from two lines of triples to two lines of duples:

da Dum da da Dum da da Dum da da Dum da

Dum da Dum da Dum

da Dum da Dum da Dum

“When” probably isn’t stressed. In context, “I” could be stressed if someone else was coming home. “Got” could be stressed if the lights came on (maybe a surprise party) soon afterwards. But most likely, we are looking at da da da Dum da Dum da Dum: When I got home the house was dark.

It is quite clear what the first three words are not. They are not the most important words in the phrase — typical for words in gray areas. Even if some words aren’t so clear, you know which ones work the hardest. No problem setting this phrase to music — just save the stressed beats for the stressed words. Work the gray ones out with a little trial and error.

In a bar of 4/4 time, the first (downbeat) and third quarter-notes are stressed. The second and fourth aren’t. This is the same pattern of strong-to-weak established by half-notes.

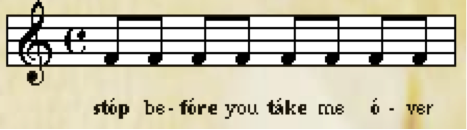

These words seem to work:

Two-syllable prepositions like “before” and “over” don’t work hard enough to put the stress in a strong musical position. The stressed 8th notes of beat two and four fit them perfectly. Not too wet, not too dry.

4/4-time is architectonic: it preserves the same pattern (strong-to-weak) through all of its subdivisions, no matter how small — eights, sixteenths, thirty-seconds, etc. This is important for setting words into measures with rests and mixed note values.

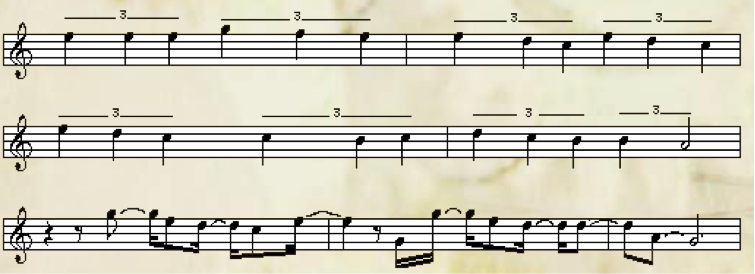

Scan this for strong beats:

The triplets in the first four bars are easy, lining up

Dum da da Dum da da Dum da da Dum da

Bars six and seven are the most interesting.

(Dum)/ da Dum da Dum da Dum. The anticipation of beat three is clearly stressed. The anticipation of beat four is, again, less strong. The dotted eighth ending bar six seems unstressed, even though it is tied to a downbeat. In the context of the phrase, it pales with all the strength around it. It is too far away from the downbeat. Similarly, the final cadence is subdued, ending as an anticipation of beat two, though its length gives the note a little extra punch. What words would fit this music? Try these:

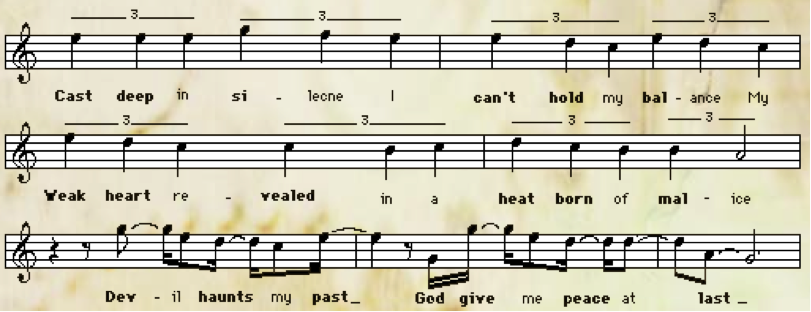

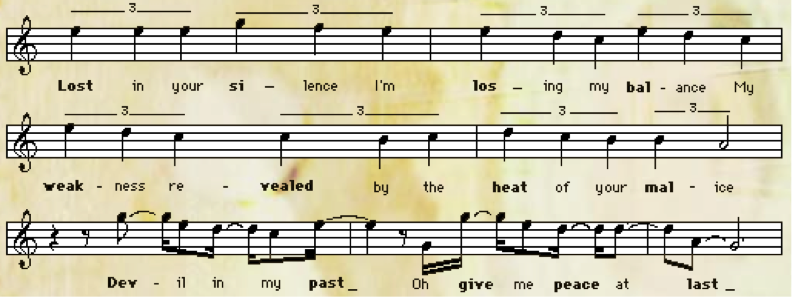

Lyricists spend a lot of time trying to match patterns — word patterns to note patterns, or words to words, like writing a second verse to match a first. What if you had to write another section to match this one by Sting? Look at it closely. Not only should you line up your stressed and unstressed syllables exactly the same, you also should put your most important words in the same places. Look at this try.

My weak heart revealed in a heat born of malice

Devil haunts my past

God give me peace at last

My weak heart revealed in a heat born of malice

Devil haunts my past

God give me peace at last

Look at all the places where stressed syllables appear in unstressed musical positions. These “greedy” spots sound hurried and unnatural, calling attention away from the emotion of the line. Cool dry spots would have trouble connecting with such sweaty bruisers. It would be a bad match, not to mention bad prosody.

Look at all the places where stressed syllables appear in unstressed musical positions. These “greedy” spots sound hurried and unnatural, calling attention away from the emotion of the line. Cool dry spots would have trouble connecting with such sweaty bruisers. It would be a bad match, not to mention bad prosody.

How about this one?

My weakness is now in the place of your malice

Won’t you help me past

And get me out at last

My weakness is now in the place of your malice

Won’t you help me past

And get me out at last

This one’s too cool. It pretends to say something in all those important musical places, but ends up just sounding overwrought. Enough to lose anyone’s interest, especially those sweaty notes hoping for someone to match their passion.

Another try:

My weakness revealed by the heat of your malice

Devil in my past

Oh give me peace at last

My weakness revealed by the heat of your malice

Devil in my past

Oh give me peace at last

Marital bliss. This one is just right, matching the prosody of the original. Note and word stresses match, and the most important words are in the same places. Stressed with stressed, Unstressed with unstressed.

Now it’s your turn to write a perfect match to Sting’s music. Take your time, and write a better one than I did.

Happy matchmaking!

It isn’t too long a drive up to Maine, though it’ll take at least a couple hours. Uncle Ed says, “Take I-95 all the way. It’s quick. Just get here. We want to see you.” Of course Aunt Edna wants me to have a nice, scenic trip. “When you get to Portland, take 1-A along the ocean. Take your time. It’s a beautiful drive.”

And of course I know that the first question they’ll ask is “So, what route did you take?” Whichever answer I give, one of them will stiffen a little. It’s kind of a competition between them. What to do?

I can’t follow both routes.

First, watch this video.

In the lead song from Lady Antebellum’s self-titled hit album, “Love Don’t Live Here,” they invite us to take a journey. The song contains roadmaps, telling us how to proceed, where to go next, what connects to what, when to pause for a rest, when and where to stop.

Listen to the song here.

Let’s look at their verses. (I’ve omitted the pre-choruses and choruses):

Verse One:

It might take some time/to get back what has gone

But I’m moving on/and you don’t hold my dreams

Like you did before/ and I will curse your name

Just passing through/to claim your lost and found

But I’m over you/ and there ain’t nothing that

You can say or do/to take what you did back

Verse Three:

And try to justify/ everything you did

But honey I’m no fool/ and I’ve been down this road

Too many times with you/ I think it’s best you go

Look at the first two lines of verse one, the beginning of our trip:

It might take some time/to get back what has gone

The first line of verse one is a complete idea:

The second line is also a complete idea,

But look at the last two lines of verse one:

Like you did before and I will curse your name

In these lines the melody and lyrics are at odds. They want you to get off at different exits. While the melody still defines a 2-idea group, the lyric ideas are arranged either as

and I will curse your name

and you don’t hold my dreams like you did before

and I will curse your name

Here comes verse two:

Just passing through/to claim your lost and found

But I’m over you/ and there ain’t nothing that

You can say or do/to take what you did back

and there ain’t nothing that you can say or do to take what you did back

OK, so what can we do about it?

The goal, of course, is that the lyric and melody work together – that they create compatible roadmaps, supporting each other and making the combination stronger than either the lyric or melody alone.

In general, there are two strategies for solving these mis-matches:

2. Change the lyric to match the melodic roadmap

Like you did before/ and I will curse your name

Though you did before/ now I curse your name

But there’s also a little trick for you to file away for future travelling, a third technique: try repeating something from the first line at the beginning of the next line:

Hold ‘em like you did before/ and I will curse your name

Let’s add it to our two strategies:

2. Change the lyric to match the melodic roadmap

3. Repeat a word from the first line at the beginning of the next line.

You can say or do/to take what you did back

Of course, you could match the lyric’s roadmap to the melody by finding different rhymes and lines. Maybe something like:

No matter what you do/there’s no way I’ll forget

(thaaat)

You can say or do/to take what you did back

This might be a perfect place to try the third strategy – repeating that:

That you can say or do/to take what you did back

2. Change the lyric to match the melodic roadmap

3. Repeat a word from the first line at the beginning of the next line.

And try to justify/ everything you did

But honey I’m no fool/ and I’ve been down this road

Too many times with you/ I think it’s best you go

Too many times with you/ I think it’s best you go

The lyrical roadmap is,

and I’ve been down this road too many times with you

I think it’s best you go

But honey I’m no fool/ I think it’s best you go

I think it’s best you go/ ‘cause honey I’m no fool

Creating compatible roadmaps melodically and lyrically is essential to getting maximum meaning and impact from your song. Ignoring mis-matched roadmaps creates a fourth option:

2. Change the lyric to match the melodic roadmap, or

3. Repeat a word from the first line at the beginning of the next line.

4. Keep it the way it is, since no one listens to lyrics anyway

If you try to follow both maps, you’ll end up not knowing where you are. Your listener, in the presence of conflicting sets of directions, will be thinking about something other than what you’re saying, and may never get to taste Aunt Edna’s special recipe for cranberry stuffing.

Your choice.

Listen to the song here.

Here’s the lyric:

Oh, did I almost see?

What’s really on the inside?

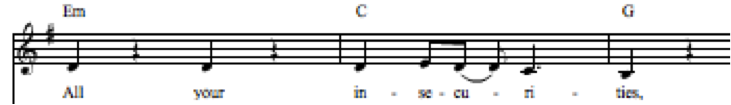

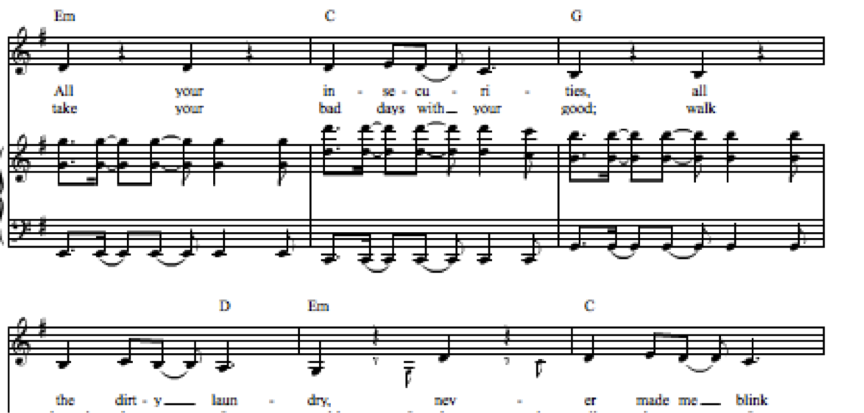

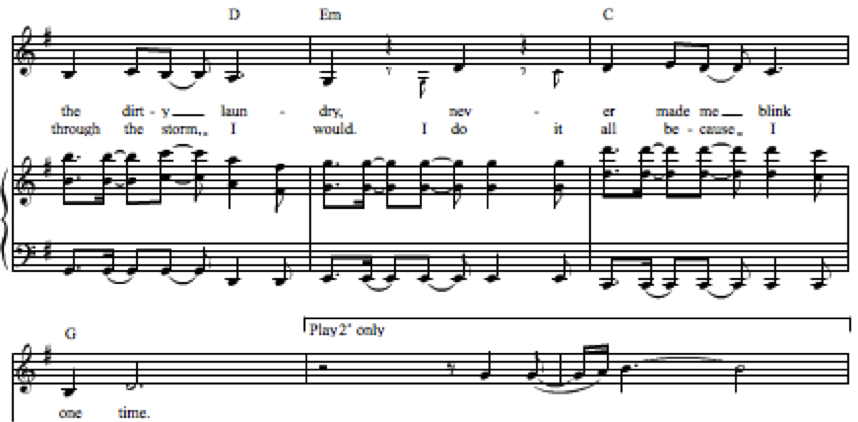

All your insecurities

All the dirty laundry

Never made me blink one time

Unconditional, unconditionally

I will love you unconditionally…

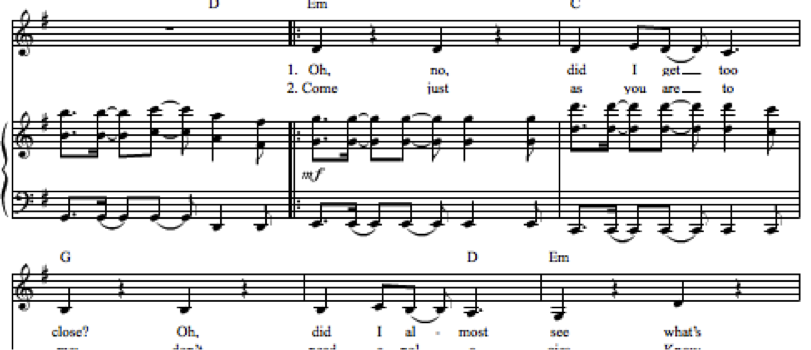

First, the natural stresses of “Oh no” are reversed. In speech, “no” is more stressed (higher pitch) than “oh.” The placement of “oh” on the downbeat and ‘No” on the 3rd beat makes it sound like we’re addressing John Lennon’s wife by her last name, “Ono.”

Next, “did” is puffing up its chest on the downbeat of bar 2, “get” is anticipating beat 3, and “too,” the intensifier (thus stressed) is shoved into the dark corner of beat 4. The result is the unnatural:

See?

And that’s only the first line. Not a promising start. Line 2:

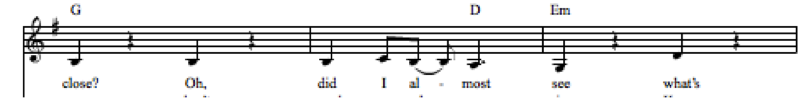

Once again, “did” is having a great time prancing around on the downbeat. The rest is alright, but the mis-setting of “did” mis-shapes the language into the strange:

What’s really on the inside

What’s really on the inside?

2. Oh, did I almost see what’s really on the inside?

Right. In “What’s really on the inside?” “what’s” is stressed, as it should be in its identity as an interrogative pronoun, introducing a question.

But in “Oh, did I almost see what’s really on the inside?” “what’s” is a relative pronoun and is, like all relative pronouns, unstressed. Now look at the musical phrasing:

First, “What’s” is stressed in its position in the 3rd beat of the bar, coming down on the side of a question introduced by the interrogative pronoun.

Second, the rest between the phrases,

What’s really on the inside?

What’s really on the inside?

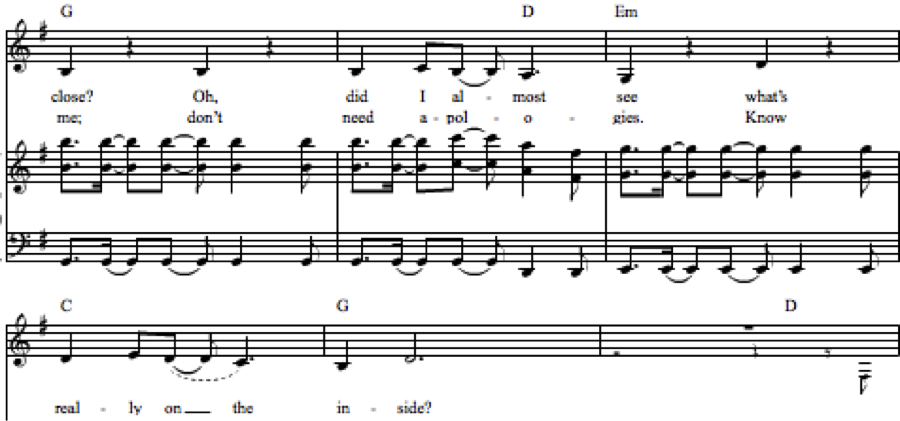

The song has stumbled and broken its leg out of the starting gate. But now, the real fun begins:

Wrong.

It’s hard to believe. “All” is on a 3rd beat. Fine so far, but “the” on a downbeat? And the weak syllable of “dirty” on beat 3? The coup de gras: the weak syllable of “laundry” on a downbeat! Sheer insanity:

The stressed syllable of “Never” is on beat 3, and the unstressed syllable is in the powerful downbeat position. The unstressed pronoun “me” is on beat 3 and the strong verb “blink” is relegated to the corner in beat 4. Additionally, “time,” which is stronger than “one” is in a weaker position.

Enter Ed and Edna:

Never made me blink one time

All this before we even get to the most laughable part of the song. The idea is, by this time, DOA (dead on arrival). Still, let’s have a last kick at the totally inert carcass of this song:

I will love you unconditionally…

I will LOVE you unconDItionally …

Of course, there’s the egregious setting of uncondiTIONalLY, with the primary musical stress in exactly the wrong place, but equally ugly is the emphasis on the pronouns at the expense of “love,” on the 4th beat of the bar, making it sound like “I will a view.” Not to mention the final syllable, LY, on a downbeat.

Finally, another terrible setting of unCONdiTIONalLY, after the non-declaration of love.

I will love YOU unCONdiTIONalLY…

The same is true in poetry, at least in poetry that attempts to establish a rhythmic base: the entire panoply of poems written in iambics, essentially 2/3rds of the poetry written in English. They work like songs, in that the meter (or iambic pulse) that creates motion is joined to words. Unlike songs, the meter only creates expectations that the iambic pattern will continue, whereas in songs the music and lyric are articulated simultaneously.

The poet sets the meter up by creating patterns of unstressed and stressed syllables, then departs from the da DUM da DUM pattern to make an expressive point.

Once again, the natural stresses of the language need to be served in order to make the poet’s syncopations against the pulse effective.

Let’s start with two lines from Keats, who’s talking to a vase:

Thou foster child of silence and slow time

—Ode on a Grecian Urn—

da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM da…

da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM da da

The second line is even stronger:

da DUM da DUM da DUM da…

da DUM da DUM da DUM da da DUM DUM

Wonderful prosody is created by these syncopations. They enhance and support the meaning while, at the same time, creating a spotlight by surprising us—not doing the expected. That’s the gig for these poets. They do it very well.

Note that the syncopation is achieved by creating variations in the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. Stressed and unstressed syllables are the fundamental building blocks both for establishing the pattern and creating variations.

The variation is NOT achieved by keeping the same rhythmic pattern and mis-stressing syllables.

da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM da da

da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM

da DUM da DUM da DUM da da DUM DUM

da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM

The technique of pattern and variation is simple and straightforward. You don’t have to distort the natural shape of the language, because all you have to do is arrange the natural stresses (the ordinary language) so that THEY create the variations, while keeping our attention focused on meaning. Distorting the shape pulls our focus away from meaning rather than supporting it and enhancing it.

In my view, the same principles apply directly to the matching stressed notes with stressed syllables and unstressed notes with unstressed syllables. Don’t mismatch them, rather, use the musical patterns of weak and strong (matched perfectly with syllables) to create expectations, then use the musical variations (matched perfectly with syllables) to enhance and support the meaning. All the while preserving the natural shape of the language, thereby keeping attention focused on meaning.

I will love you unconditionally…

unconDItional, unconDItionally

I will LOVE you unconDItionally

I will love YOU unCONdiTIONalLY

Mantra: Preserve the natural shape of the language.

I have no doubt that Wittgenstein, not only a philosopher, but a consummate musician, would agree.