One would think the story’s dreamlike qualities, as well as its relative brevity, would make it difficult for a filmmaker to adapt. And perhaps one might be forgiven for being skeptical about whether director and producer Roger Corman, widely known for low-budget wonders like A Bucket of Blood and the original Little Shop Horrors, could be the right man for the difficult work of bringing this vaunted piece of literature to the screen.

And yet: Corman invested his series of Poe adaptations (which began with The Fall of the House of Usher in 1960) with admirable ambition. Though these films were produced on relatively tight budgets (with sets and costumes recycled from one picture to the next), they also managed to boast a certain lavishness not seen in many American horror films in the 1960s or even today: actors in elaborate, vaguely period costumes lounge about on ornate sets in lush, artificially vibrant color. At one point in Corman’s 1964 version of The Masque of the Red Death, Prince Prospero implores a young woman to let him lead her “through the cruel light into the velvet darkness” (Masque), and it sometimes feels like the director is making a similar proposition, luring us ever deeper into Prospero’s depraved but fascinatingly opulent world. Masque was one of the last films of Corman’s Poe series, and it is perhaps the best of the bunch – it honors and thoughtfully interprets its source material even as it embroiders on it.

Poe sketches Prince Prospero over the course of his story’s few pages, using the prince’s name to suggest wealth and his disregard for the outside world as an indictment of those in power who ignore the suffering of others. Poe’s Prospero wrongly believes he can buy off death, but the story’s conclusion asserts death’s status as an equalizer that comes for prince and peasant alike. Faced with expanding Poe’s story into a feature film, Corman and his screenwriters Charles Beaumont and R. Wright Campbell must flesh out Prospero’s character, and they create a man who is both decadent and sadistic. The audience gets a sense of who Prospero is immediately upon his entrance into the film – his carriage horses nearly trample a child in an impoverished village. In the same scene, Prospero hears a woman in the village scream, and haughtily instructs his henchmen to, “Silence that!” (Masque). Discovery of an old woman who has succumbed to the Red Death elicits Prospero’s casually delivered directive to “burn the village to the ground” (Masque). Played with unrelenting viciousness by horror icon and Corman regular Vincent Price, this Prospero’s hubris is outdone only by his cruelty.

The film notably incorporates another Poe story, the slightly more obscure “Hop-Frog,” as part of its narrative. “Hop-Frog,” which was also memorably adapted as the TV movie Fool’s Fire by Julie Taymor in the 1990s, tells the story of a man with dwarfism and limited mobility in his legs who exacts brutal revenge on a king and his seven ministers after they torment him and a young woman named Trippetta. Both Hop-Frog and Trippetta were, Poe writes, “forcibly carried off from their respective homes in adjoining provinces, and sent as presents to the king by one of his ever-victorious generals” (Poe, Complete Tales 441). The narrator of the story speculates that Hop-Frog’s name “was conferred upon him, by general consent of the seven ministers, on account of his inability to walk as other men do” (Poe, Complete Tales 441). These details help to establish the story’s preoccupation with abuses of power; “Hop-Frog” is a revenge fantasy in which an individual is dehumanized by the rich and powerful, and so furiously lashes out.

In Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death, Hop-Frog is (somewhat inexplicably) renamed Hop-Toad, and Trippetta is renamed Esmeralda. Presumably for budgetary reasons, one man, Prospero’s similarly aristocratic, and similarly cruel, friend Alfredo, represents all of the royal ministers. Though the film’s “Hop-Toad” character does not share the original Poe character’s difficulties with walking, the filmmakers remain true to one of the short story’s dominant themes: that of privileged people failing to acknowledge the humanity of marginalized people. What’s more, they identify this theme as a common thread between Poe’s “Hop-Frog” and “The Masque of the Red Death,” and thus underscore the theme’s significance. The film version of Prospero is based partially on the king from “Hop-Frog,” and the combination works. “Pretty toy, isn’t she?” Price’s Prospero muses aloud while Esmeralda is dancing (Masque). This moment resonates with another from later in the film, when Prospero forces two peasant men from the plague-ravaged village to play a deadly game with poisoned daggers, dubbing the event “a small entertainment” for the amusement of his wealthy guests (Masque). In both instances, Prospero behaves as though his status and wealth authorize him to treat people as objects.

While it’s true that the film’s version of Prospero humiliates even his aristocratic guests (in one memorable scene, he pressures a number of them to behave like animals for his amusement) and registers scant regret when others of his own class are killed, he reserves his most exploitative behavior for those he considers inferior: the poor, women, and those like Hop-Toad and Esmeralda who look different than himself. Prospero sees the film’s protagonist, Francesca, a poor woman from the doomed village, as his property, entering a room when she is bathing, dressing her as he pleases, and making repeated, thinly-veiled references to his plans to coerce her into sex. Though it can certainly be argued that The Masque of the Red Death is an exploitation picture that, like Prince Prospero, leers over women and presents violence as spectacle, the film’s characterization of Prospero nevertheless represents a logical extension of Poe’s version of the character, particularly for those who interpret the original tale as a story that is at least partly about socioeconomic class.

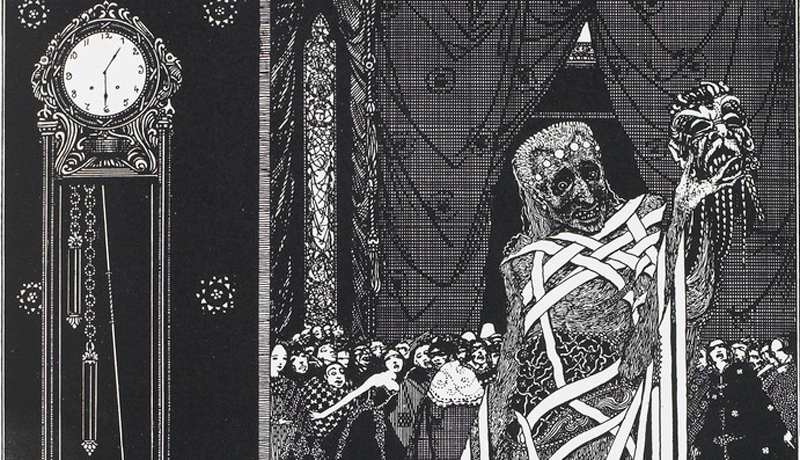

Yet I don’t mean to suggest that the film is a humorless meditation on inequality. Though it is substantial enough to be a worthy and interesting adaptation of Poe’s text, Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death is also a fun watch, and at times, lovably camp. Price never winks at the camera but is obviously enjoying tearing into his wicked role. His Prospero is not just a hedonist and likely sociopath, but also an avowed Satanist, and it’s hard not to crack a grin when, having already identified his “master” as the “lord of the flies” and a “fallen angel,” Prospero silently mouths a final epithet –“the devil” – with giddy relish (Masque). And yes, the film’s climactic “dance of death” – in which bloodied dancers with blood red skin encircle Prince Prospero – is at once eerie and kitschy.

Nevertheless, Corman’s film feels most of all like a tribute to Poe, one that emphasizes the still-relevant themes of power and inequality in both “The Masque of the Red Death” and “Hop-Frog.” While Poe could not have anticipated the arrival of cinema as an art form or the popularity of his stories as source material, and we cannot venture to know how he would have felt about either development, Corman’s Masque does at least seem to adhere to some of the guidelines Poe set fourth in his famous essay, “The Importance of the Single Effect in a Prose Tale.” In that piece, Poe argues, “that, in almost all classes of composition, the unity of effect or impression is a point of greatest importance” (Poe, “Importance” 945), suggesting that every element of a story should be included as a means of leaving a single, desired impression on the reader. Though literature and certainly cinema are too rich with ambiguity to fully comply with Poe’s directive, most every element in Corman’s Masque exists to wring terror out of a situation where a privileged man not only grossly abuses his power but also unwisely seeks dominion over death itself. What’s more, the film, which comes in at a lean 90 minute running time, seems to share Poe’s reverence for economy. In “Single Effect,” Poe praises short prose “requiring from a half-hour to one or two hours in its perusal” for its ability to place “the soul of the reader…at the writer’s control” (Poe, “Importance” 945) without interruption. Corman’s film takes control of its viewers’ souls for an hour and a half, leaving in its wake a unified impression of social critique couched in bloody horror. I would like to think Poe would be proud.

Poe, Edgar Allan. Complete Tales & Poems. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 2002. Print.

—. “The Importance of the Single Effect in a Prose Tale.” The Story and Its Writer: An Introduction to Short Fiction. Ed. Ann Charters. Compact 9th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2015. 944-947. Print.

The Masque of the Red Death. Dir. Roger Corman. Perf. Vincent Price, Skip Martin. American International Pictures, 1964. Film.