Who went to see the Elephant (Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation, Might satisfy his mind.

Against his broad and sturdy side, At once began to bawl:

“God bless me! but the Elephant, Is very like a WALL!”

So very round and smooth and sharp? To me ’tis mighty clear,

This wonder of an Elephant, Is very like a SPEAR!”

The squirming trunk within his hands, Thus boldly up and spake:

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant Is very like a SNAKE!”

“What most this wondrous beast is like, Is mighty plain,” quoth he:

“Tis clear enough the Elephant Is very like a TREE!”

Can tell what this resembles most; Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant, Is very like a FAN!”

Than seizing on the swinging tail, That fell within his scope,

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant Is very like a ROPE!”

Each in his own opinion, Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right, And all were in the wrong!

I grew up in a very conservative catholic home where a huge picture of a blond, blue eyed Jesus hung above the sitting room sofa. Many of my friend’s homes had more or less identical pictures with slight variations in the color of Jesus’ hair and eyes, but He remained undeniably Caucasian. We had a children’s Bible at home illustrated with pictures. In the Bible, as in the picture hanging on our wall, Jesus is white. Judas Iscariot , the disciple who denied Jesus is darker than Jesus but still Caucasian. The angels with their feathery wings have long, silky hair and white skin. The only black character is the devil with a tail and a pitch fork held between his hands. Yet, despite this, I had taken it for granted that if I lived well, heaven would have a space for me in it too., thet in Heaven I’d be scrubbed to white perfection. My mother painted vivid pictures of hell to keep her seven children on the straight and narrow. She mostly succeeded and so It was a blow to read that I was destined to hell for something I had not done. I thought it grossly unfair but I felt completely helpless to do anything about it. I did not question the veracity of the book I read because I believed in the authority and the integrity of the written word, but also because at that age, everything else I had read affirmed the truth of the book: the world was polarized ; white was good and the ideal to strive for, black was bad. I therefore thought my fate was sealed, and spent many nights having nightmares where the devil chased me round with his pitchfork, laughing as I tried to escape his clutches,. I woke up from these nightmares too scared to leave my bed. I did not share my fears with my parents because how could they console me, if I saw all around me evidence that the book was right?

I was in elementary school then, and as my parents were middle class, I was sent to a good school. A good school in those days (and perhaps now still) in Nigeria, as in many parts of Africa colonized by the British, was one in which classes were taught in English, and pupils were not allowed to speak in any of their native languages. It was a major offense in my school- as it was in other schools of the same standard- to use – what is called- “vernacular” at any time during school hours. Nigeria has over 350 local languages but any pupil caught speaking in any of those was punished. Punishment ranged from being made to pay a fine to forfeiting a meal. Bwesigwe, a Ugandan writer notes in a recent article that in some schools in Uganda, students who are caught speaking a native language are shamed by being made to wear sack cloths the entire day. He also writes that in one school, the offending student is made to pin a sheet of paper to his chest and back with the words, “I am a vernacular speaker.” Such a student is jeered by other students and mocked by the teachers.

At school, in social studies class, we learned that the wife of a British administrator named Nigeria (while she was still his girlfriend). We learned that a European explorer, Mungo Park, ‘discovered’ the River Niger. Whatever we learned of Nigerians taking an active part in Nigeria was limited to the patriots who fought for our independence . It was almost as if before then, before the English came in 1849 to colonize it, Nigeria was a huge void where nothing and nobody existed. That is the danger of Reading the Single Book. Nothing I had read up until then challenged the notion that I was somewhat inferior to the German family who lived in the flat below us. Nothing challenged the notion that I was valid enough to be a character in a book. An Igbo proverb says that until lions learn to tell their own tales, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.

Fortunately, an older, wiser writer had already begun the process of re-thinking what I had swallowed whole heartedly and had begun to articulate his thoughts in fiction., telling the story of the lions. That older, wiser, writer was Chinua Achebe. .Not long after I read that distressing book whose title I no longer remember, serendipity threw Chinua Achebe’s debut, Things Fall Apart in my path. In 1958, Things Fall Apart became one of the earliest books by an African writer to be published in the UK.

Things Fall Apart tells the story of a civilization and a community completely disrupted by the coming of the white man. Its protagonist, Okonkwo, is a warrior, a proud man whose life is completely ruined by the clash of civilizations which is brought by the English colonizers. For the first time in my life, I read a book which showed that my ancestors had a history before colonization, a world that was complete on its own and which did not seek validity outside of its own community. For the first time, colonization was presented as an intrusion, and not as something I ought to be grateful for. Achebe writes in the novel:

In a 1994 interview with the Paris Review, Achebe himself says:

Then I grew older and began to read about adventures in which I didn’t know that I was supposed to be on the side of those savages who were encountered by the good white man. I instinctively took sides with the white people. They were fine! They were excellent. They were intelligent. The others were not . . . they were stupid and ugly. That was the way I was introduced to the danger of not having your own stories… Once I realized that, I had to be a writer. I had to be that historian…”

When I moved to Belgium and began to write, I wanted to, like Achebe, be a historian as well, telling the stories of my Africa because I had been confronted by people who spoke of Africa as if it were a country. I also, wanted to, I suppose get into a conversation with fellow Africans for whom the stories are familiar. This is perhaps most evident in the first book I published in Belgium, The Phoenix..

One of the most hopeful Igbo proverbs I know says that the chicken scratches ahead and scratches behind and asks her children which is better. Its implication is that the future is greater than the past (or the present) : Nkiruka. Scratching is an act of writing, and one could argue that the chicken’s children come to the answer to their mother’s question through reading her multiple scratchings. We cannot grow if we read the single book.

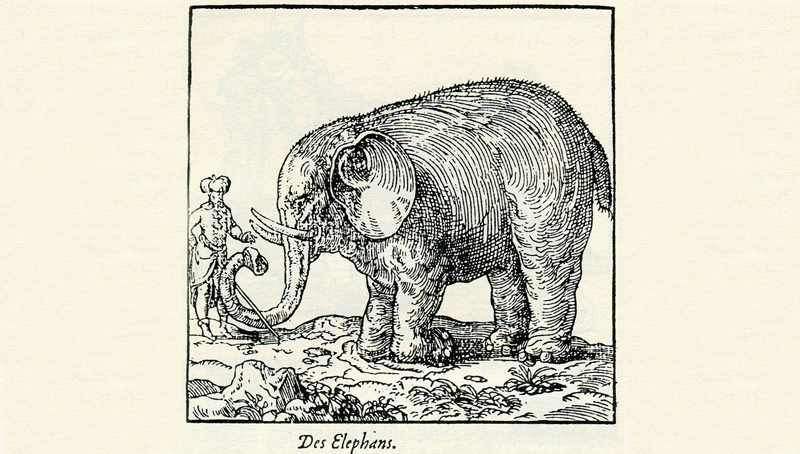

André Thévet [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons